America’s journalists aren’t just inaccurate – they’re in league with the enemy. That, at least, seemed to be the message from President Trump when he spoke to America’s military commanders on Monday.

ISIS, he said, were waging “a campaign of genocide”: “All over Europe it’s happening. It’s gotten to a point where it’s not even being reported and, in many cases, the very, very dishonest press doesn’t want to report it. They have their reasons and you understand that.”

When the White House followed this up by publishing a list of ISIS or ISIS-inspired attacks that, it said, had mostly been underplayed by the media, there was widespread derision. Online galleries showed front page after front page devoted to the attacks that had apparently been ignored.

For many, this episode represents the latest instalment of Trump’s war on the media. But actually, I think it reflects something more profound.

The new President, and his policy chief Steve Bannon, see the world not through rose-tinted glasses, but through blood-splattered spectacles. They see an America in which crime is rising, the inner cities are in flames, the factories are closing, the Chinese are rising, and Islamist fanatics lurk in every mosque.

“Make America Great Again” is a statement that America has fallen from greatness. And if the media’s reporting fails to reflect this, then it must be the media that is deluded – or actively conspiring to hide the truth.

The irony is that this narrative is simultaneously exactly right and exactly wrong. Exactly right because the media’s reporting is indeed distorted. And exactly wrong because it is distorted in precisely the opposite way.

The media is in fact, as I have argued before on CapX, biased towards pessimism and drama. And it distorts the world not by presenting it as a better place than it is, but a worse one.

Here, for example, are just a few things that it gets wrong.

Overreported: Terror attacks in the West

Underreported: Terror attacks elsewhere

President Trump’s travel ban on nationals from seven Muslim-majority countries was not, Rudy Giuliani insisted, due to religion, but “danger”. But as Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute points out, that’s nonsense.

Between 1975 and 2015, foreigners from those countries killed precisely zero Americans on US soil.

Yes, six Iranians, six Sudanese, two Somalis, two Iraqis and one Yemeni were convicted of attempting or carrying out terrorist attacks, but many others accused of terrorist-related offences were, in fact, common or garden criminals – like the three men accused of trying to purchase a rocket-propelled grenade launcher, who in fact went down for receiving two truckloads of stolen cereal.

As for the ban on refugees, only three Americans have been killed in terrorist attacks committed by them – and those were Cubans in the 1970s. As Nowrasteh says (emphasis his): “Zero Americans have been killed by Syrian refugees in a terrorist attack on US soil. The annual chance of an American dying in a terrorist attack committed by a refugee is one in 3.6 billion.”

Where Trump and co do have a smidgeon of a point is that the danger is higher overseas. As the Global Terrorism Index 2016 points out, deaths from terrorism in OECD member countries “dramatically increased in 2015, rising by 650 per cent when compared to 2014”. All told, 21 of the 34 OECD countries experienced at least one terrorist attack.

But this rise was from a blessedly low base. It is still the case that the overwhelming proportion of terrorist attacks are in Iraq, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan and Syria – in other words, where the terrorists are. These five countries, says the GTI, “accounted for 72 per cent of all deaths from terrorism in 2015” – which actually decreased worldwide by 10 per cent.

In other words, terrorism as a global phenomenon is not a product of religious fundamentalism, but the broken states in which it can thrive. All told, the GTI reports, “only 0.5 per cent of terrorist attacks occurred in countries that did not suffer from conflict or political terror”. Yet those 0.5 per cent of attacks end up getting vastly more of the coverage.

Overreported: Terror attacks (everywhere)

Underreported: Lightning, toddlers, lawnmowers etc

Within the context of terrorism as a problem, the media tends to focus far too much on the West and far too little on the countries where it’s actually happening.

But the truth is that outside of those five hotspots mentioned above, terrorism isn’t actually that much of a problem, full stop – certainly not in comparison with the resources that are lavished on preventing it.

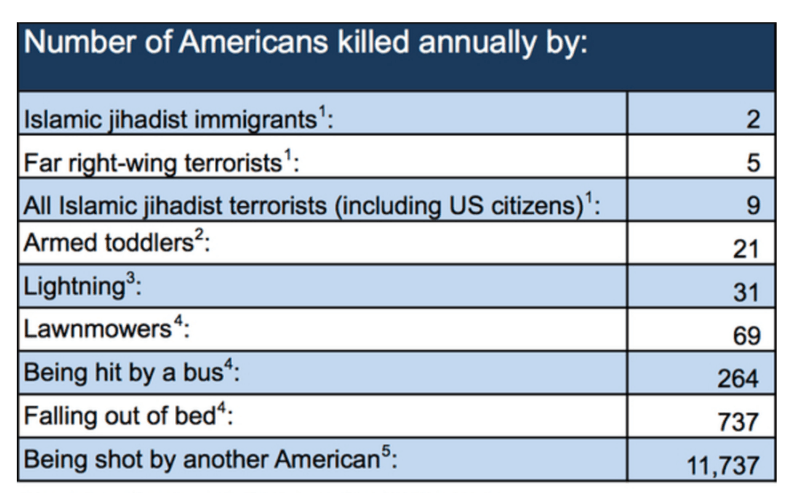

Back in September, Todd R Miller wrote a piece for the Huffington Post setting out just exactly how uncommon terrorist attacks are as a cause of death in the US, compared to all the rest of life’s hazards, such as getting struck by lightning, getting hit by a bus – even getting shot by a toddler or falling out of bed.

But even globally speaking, terrorism is a tiddler. As the World Health Organisation’s statistics on causes of death show, there are all sorts of things that kill vastly more people – road accidents, for example. Falls, drownings, epilepsy, fires, poisonings, alcohol, syphilis, tetanus, appendicitis – all are far deadlier threats, numerically speaking.

Overreported: Gun deaths (murder)

Underreported: Gun deaths (suicide)

During the Obama presidency, it seemed that every week brought news of another mass shooting in America.

But the fact is that most gun deaths in America aren’t the result of deliberate shootings – or even accidental ones, despite those trigger-happy toddlers mentioned above.

Even back in the 1980s and 1990s, when violent crime rates were (contra Trump) far higher, more people in America were using guns to kill themselves than to kill others. In 2010 – to take a sample year – guns were used in 11,078 homicides in the US, comprising roughly a third of all gun deaths and two thirds of all homicides.

But in that same year, firearms were used in 19,392 suicides – consisting around three fifths of all gun deaths. Suicide is, as the New York Times points out, the second most common cause of death for Americans between 15 and 34, causing 1.6 per cent of all deaths in 2012. And a majority of those suicides involve the use of a firearm – usually in the hands of a white male.

Of course, in this instance there is an argument in mitigation: the media (at least in the UK) tends not to report on the details of suicide, given that such reporting has been proven to cause copycat deaths.

But it is certainly the case that the media underreports the one and overreports the other – as well, for that matter, as focusing disproportionately on mass shootings as opposed to everyday gun crime, the victims of which in the US are overwhelmingly black.

Overreported: Violent crime

Underreported: Fraud

If there’s one thing that the reading public can agree on, it’s that they love a juicy murder. From Mr Whicher to OJ Simpson, a sensationalist trial has long been just the thing for boosting circulation.

Various attempts have been made over the years to calculate how much of our media diet (both fiction and non-fiction) consists of a bit of the old ultra-violence. In 1973, Jack Katz reported that “on an average day, crime and justice represent about 15 per cent of the topics actually read”. In 1980, one estimate was that it made up 22 to 28 per cent of newspaper stories, 20 per cent of local US television news, and 12 to 13 per cent of US network news.

Yet however you define it, or measure it, there is no doubt that violent crime gets a disproportionate share of our attention. The odds of any one individual in Britain experiencing a crime of any kind, per year, is just over 1 in 10 – in 2015-1, 6.7 million adults aged 16 or over were the victims of at least one crime.

But of the 4.7 million offences recorded by police, only 1.3 million were violent crimes. This, in itself, was a spectacularly low total: the rate in 1995 was 65 per cent higher. And of these violent crimes, fewer than 20 per cent involved serious injury.

Also, bear in mind that most violent crime is, like gun crime, concentrated in a few unlucky, impoverished areas – and committed, at least in the case of murder, by people who tend to know their victims rather than random predators.

And it’s not just that we over-focus on violent crimes – we ignore crimes which are far more common. According to the Crime Survey of England and Wales, there were 5.6 million cases of fraud and computer misuse last year, almost as much as every other type of crime put together. Yet in the police statistics, just 700,000 cases of fraud show up – because the vast majority, including the 1.9 million cases of bank card fraud, aren’t reported to police.

It’s also worth pointing out here that increasing personal debt – let alone government debt – is likely to do far more damage to the average household’s prospects than any number of knife-wielding hooligans. Yet even compared to that’s a topic that gets virtually no attention by comparison.

Overreported: Bad teens

Underreported: Good teens

Teenage misbehaviour is another staple of the tabloids. As I pointed out in my recent book, it’s hard to go a day without seeing a headline about sexting or cyber-bullying or increasing mental health problems or all the other things the internet is doing to turn the next generation into vapid, shallow, frazzled creatures.

Except that that’s not actually the case. Young people today drink less, smoke less, take fewer drugs, work harder. There are fewer teenage pregnancies, fewer kids dropping out of school – to the point where Fraser Nelson can claim that Britain is actually entering a period of “social repair”.

It’s the same with other social problems. The fact is that we cover stories about homelessness, or drug addiction, or other issues not because they are so common, but precisely because they are relatively rare – and therefore newsworthy.

Yes, we’ve all got our problems. But most people are basically happy, healthy and stable.

Overreported: Bad news

Underreported: Good news

Take a look at this chart from Max Roser.

We live in exceptional times: Poverty was never lower, global education and health never better.

My global history https://t.co/SfZ0w3kDHq pic.twitter.com/mtvMAiBnyK

— Max Roser (@MaxCRoser) January 15, 2017

That doesn’t exactly seem like a planet that’s on the brink of apocalypse. And that’s because it’s not.

Contrary to President Trump, the world is becoming a better place – at a startlingly rapid clip. As Marian Tupy, Daniel Hannan, Johan Norberg and others have argued on CapX, recent decades have seen collapsing rates of poverty, disease and malnutrition, and soaring rates of literacy and prosperity.

Or read our recent articles by Professor Andrew Scott on our remarkable advances in longevity. Even as the headlines are dominated by death, we are getting better and better at pushing it further and further back. To the point, as Prof Scott says, that we may need to seriously rethink the shape of state spending.

On all of these issues and more, headlines are full of bad news because we are biologically programmed to notice it – to find it simultaneously alarming and exciting.

But in doing so, we trick ourselves. We pay more attention to a stock market crash that happens within a few hours than to the months in which the same index steadily ticks upwards. We pay more attention to famine than to agricultural immigration, to pandemics than to vaccinations, to scare stories about overpopulation than to declining birth rates.

The forces of progress are incredibly powerful, but often incredibly subtle. And it’s not just the media’s fault that we fail to recognise them: however optimistic we are about our personal prospects, our cognitive biases lead us to have an in-built pessimism about the state of the wider world, and of politics. The result is that when we look around to see where we are, we fail to realise how far we have come.

And to bring the argument full circle, this creates a broader problem – in that it is precisely our distorted view of the world which gives rise to Trump and people like him.

There is no doubt that there are many people in America who feel they have lost out in recent years – economically, culturally and even socially. But there are not enough to get Donald Trump elected without a media environment which is predisposed to report the bad rather than the good.

The biases I picked out above, and many others like them, show how the media tends to paint the world as violent, spectacular and alarming.

But that opens the door to those, like Trump and Bannon, who claim that the bad stuff is all there is – because it is all that they can see.