Dementia has become the leading cause of death in the UK. That, at least, is how the latest mortality tables from the Office for National Statistics have been reported.

Anyone who has known anyone with dementia – which is pretty much all of us – will know that it’s a terrible condition. And it’s obviously very bad news that it’s on the rise.

But there’s another story here – one that is much more optimistic.

The reason that dementia is on the rise isn’t anything to do with our lifestyles. First, it’s because we’re better at detecting and diagnosing it. And second, it’s because far more people are living long enough to develop it.

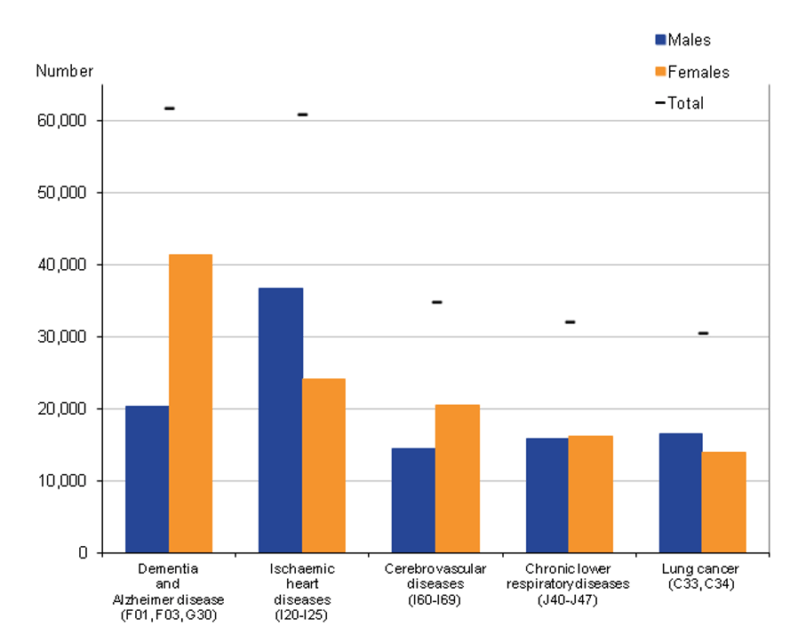

Here is the chart put out by the Office for National Statistics today of the top five causes of death in the UK. (Apologies for the quality – their graphics, not mine.)

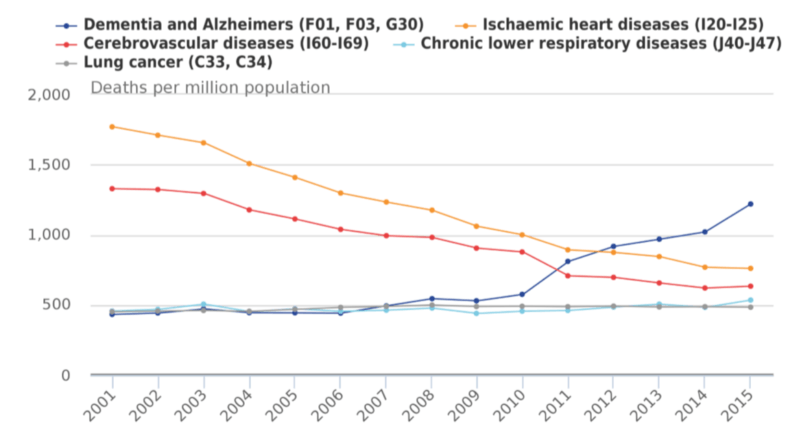

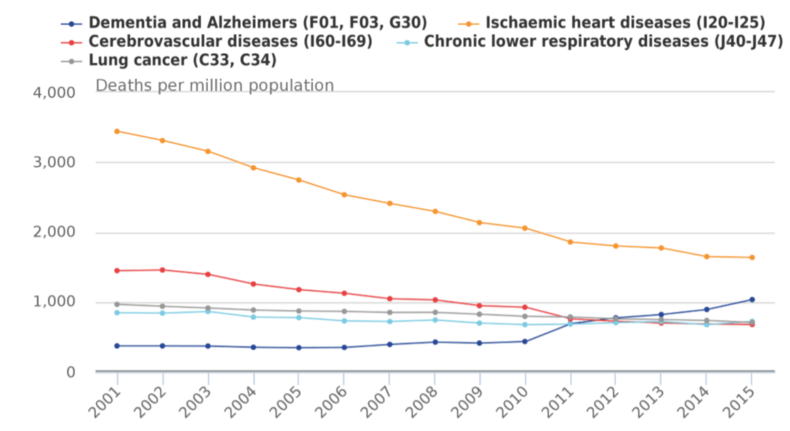

But here are the same conditions, for men and for women, tracked over time:

The surge in dementia deaths, for both sexes, is obviously concerning. But it’s been more than matched by a decline in the other big killers, in particular heart disease.

Amid headlines that shriek about war, famine and pestilence, this is one of the great underappreciated stories of our time. We have, over the past few centuries, mounted a remorseless, inexorable and astonishingly successful assault on death and disease.

In 1998, for example, the mortality rate in Britain – the proportion of people dying per year – was 8,967 per million among men and 5,928 per million among women. That was already gob-smackingly low by any historical standard.

By 2008, those figures had fallen to 6,854 and 4,898 respectively. That’s a drop of 23.6 per cent and 17.4 per cent within a single decade.

And, of course, it’s this process that has put the NHS under such financial strain: in essence, we’ve become too good at curing diseases.

What that means is that, instead of dying cheaply of strokes and heart attacks in late middle age, people arrive at hospital decades later, suffering from much more complicated – and expensive – conditions: in particular, what is known as “co-morbidity”, when a patient has multiple illnesses at once.

“We had a junior doctor fairly recently who had never seen a heart attack, because they’re now so rare,” Dame Julie Moore, chief executive of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham, told me back in 2015. “Twenty or 30 years ago, loads of people in their forties or fifties would be dropping dead. That’s a success for the NHS.”

“People with multiple organ failure, which we’re now seeing in intensive care – we never thought we’d get that,” added another senior administrator.

But our success in keeping people alive isn’t just about the elderly.

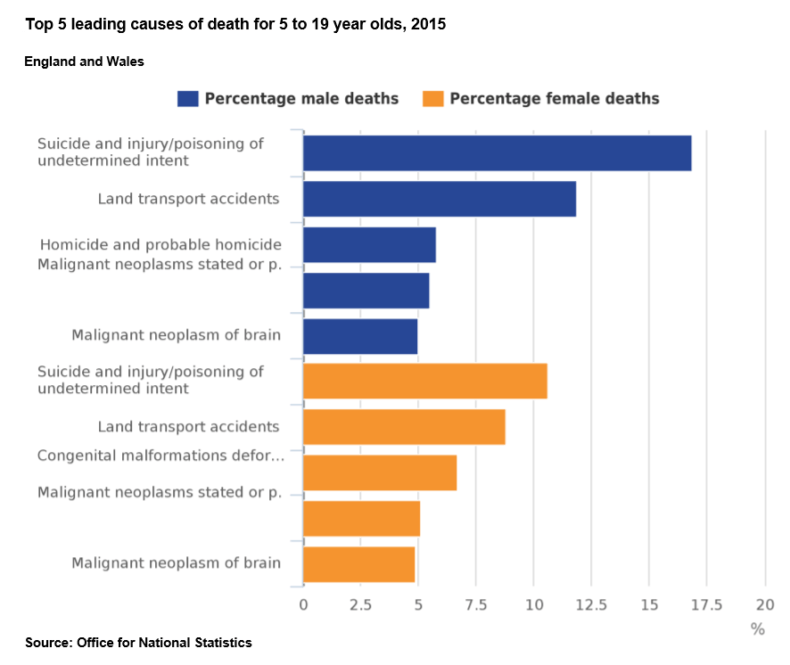

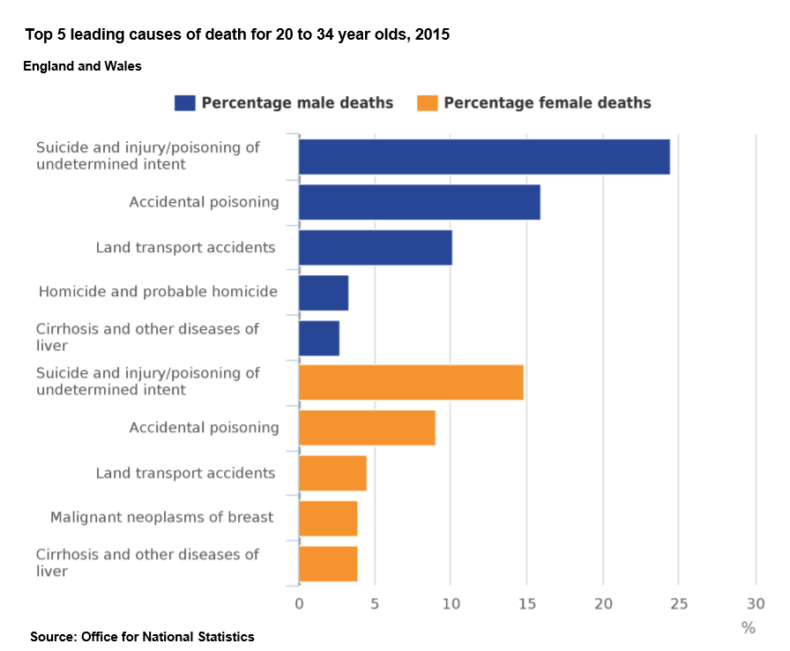

I was shocked, at a recent fund-raising event for Samaritans, to hear that suicide is now the biggest cause of death for men under 40. But it’s true, as these ONS tables show:

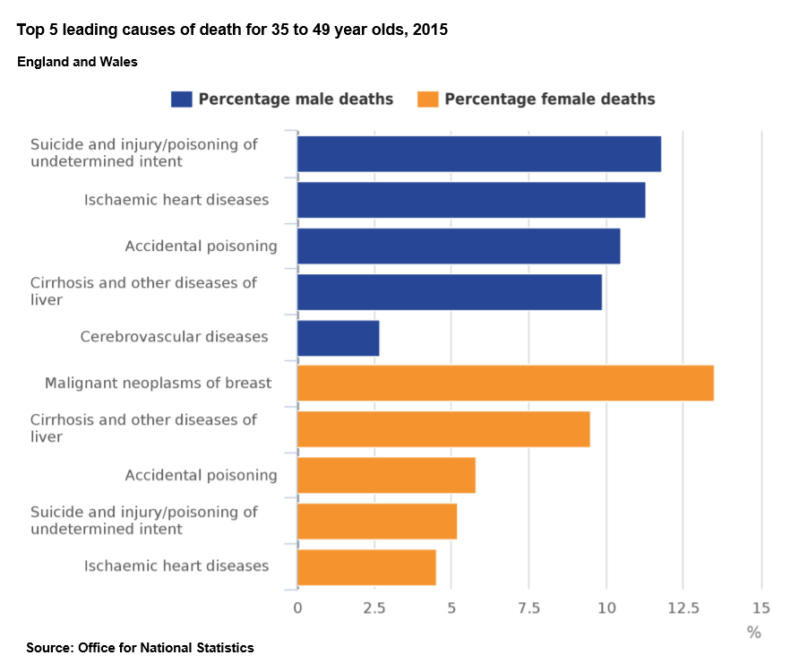

It’s not until the age of 35 to 49 that illness starts to displace suicide, as the latter rises and the former falls (although there are huge discrepancies here between the sexes):

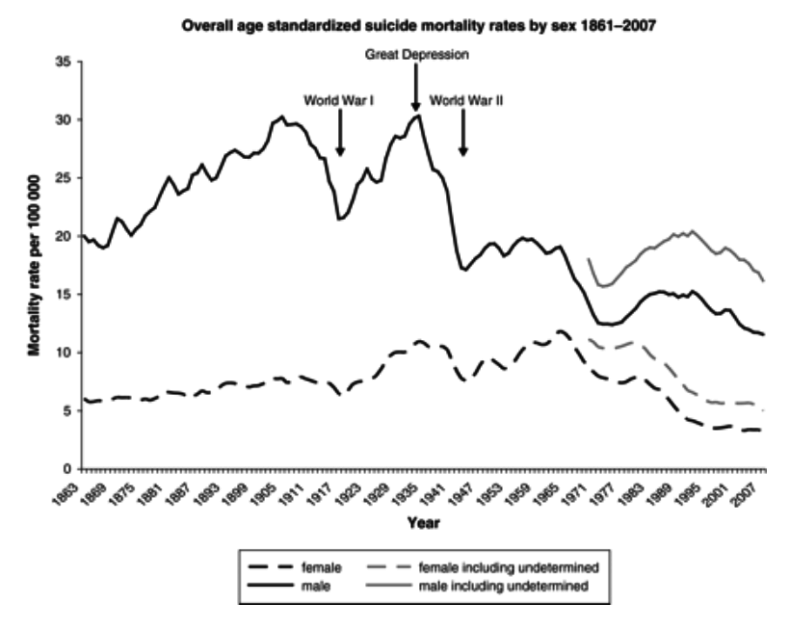

But again, this phenomenon is in many ways cause for celebration. We’ve got so good at keeping ourselves alive that those who actively choose to end their lives, rather than having them ended by illness or accident, are now dominating the statistics – and will continue to do so as we get better at curing diseases and at preventing things like car accidents, still a major cause of death among young men (which is one reason why self-driving cars can’t come fast enough).

This is, by any standards, an extraordinary accomplishment. And it’s not even as if it’s come because suicide is rising: as this academic paper found, it has been falling pretty steadily since the Great Depression (although there has been a slight uptick in the years since this chart was produced). It’s just that other causes of death have been falling faster.

Dementia is obviously, as I said above, an awful thing. But today’s news should be cause for us not just to be satisfied by our progress in extending our lives, but to marvel at it.