Over the next five years, the European Commission intends to issue €1 trillion of European Union debt to finance Europe’s recovery from the pandemic. Naturally, most of that issuance will be made more palatable and attractive by calling the new EU financings “Green Bonds” – defined as green by a framework the EU itself is writing. Ahem…

Now some folk might be labouring under the impression the EU is a customs union that got around to currency union and asking why Brussels, and not the sovereign states of Europe themselves, is financing recovery? After all, there are no treaties to say the EU is responsible for the financing of Europe, or that it should set fiscal plans and objectives.

Hah. You haven’t been paying attention then…..

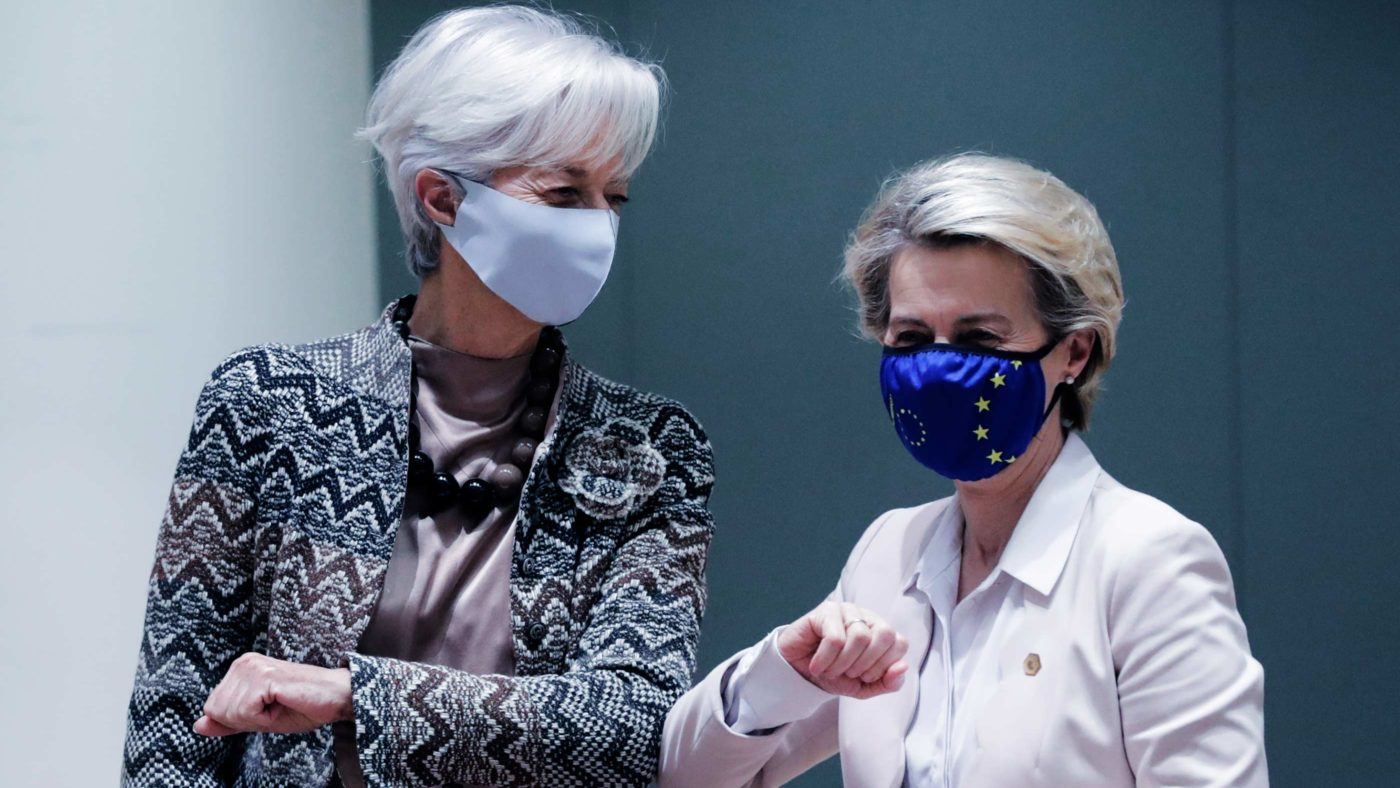

Perhaps the Euro is ‘democratised finance’ in that it’s a monetary union agreed by and overseen by every member nation in the ECB. But central banks are not democracies – if every member nation got to determine policy, it would be chaos. That’s why the ECB is presided over by a former French politician, Christine Lagarde, to ensure stuff gets done, that stuff is the right stuff, and the membership falls into line. Being head of the ECB is not your typical central banker gig.

Meanwhile, the European Commission – another not-a-democracy – will allocate the recovery funds and is run by a former German politician, Ursula von der Leyen, a lady who has been having such success with the European’s union vaccination programme. Do you discern a theme?

The key thing about the EU bond programme – which has been quietly taking shape for years – will be its eventual scale and its status as, effectively, the European Sovereign Debt market.

If you want bond exposure to Europe – what would you buy? Naturally the lowest risk is the incredibly tight and undersupplied Bund market for German debt? Or maybe the slightly more whoosh French OAT market? Or for a bit of a dare, like Italy? These are all relatively small, insular markets, best used to play themes and hunches in terms of their relative spreads and, critically, how much more the ECB is prepared to spend in terms of QE buying them on the open market.

But, but, and but again…none of these European national bond markets are truly sovereign debt. All the members of the Euro gave up their financial sovereignty when the joined the single currency. In effect the member states are merely sovereign credits – as they don’t hold the keys to the Euro printing presses, they rely on the whim of the ECB to allow them to borrow. The ECB does this by setting rules – which all the member states struggle with – which constrain them from printing money to reflate their own economies. Such constraint breeds political unrest as we saw in Greece and Italy, and now elsewhere.

Its size makes the new European Commission programme look very attractive as it lays out its alternative recovery programme and financing plans for both “Green” and “Social” bond flavours. As it effectively controls the ECB, it has monetary sovereignty. The EU has now clearly signposted its objective – to replace all the national bond markets, and compete in scale terms with the US Treasury bond market (the largest and most liquid of all). The EU is demonstrating its bonds are therefore a much better bet than the Bunds, Oats, BTPs or Bonos issued by member nations.

Except…there is no such thing as a riskless or free lunch.

The big, the massive risk, to European Commission bonds is politics. The Euro’s existence rests on the willingness of member states to stick with it, just as it’s theoretically possible – although in practice very difficult – to exit the EC. By combining all the national markets of Europe, it would become even less likely. The mutualisation of Europe’s debt is therefore a political objective for the Eurocrats in Bruxelles. But mutualisation and Brussels control will raise the level of dissent. It’s a difficult square to circle.

The big risk buying EC debt is a rupture in the political process – nations pushing back politically over the mutualisation of their debt. We know that is a massive concern for the German constitutional courts, which have pointed out the lack of any treaty signed by Germany to agree to such a burden on the German taxpayer. It’s also a cornerstone for pushback from the far-right across France and Northern Europe.

Even worse would be European nations gaming the EC debt programmes – refusing to sign or agree on vital European matters unless they were guaranteed specific pork-barrel funding from Brussels, which might just end up in shady places, heaven forbid.

At this point it might be interesting to look at an example of what happens when politics impacts markets. I thought about the unpleasantness in the Americas between the Union and Confederacy in the 1860s. Surprisingly even the domestic yield on Confederate bonds remained relatively low until the end – driven by patriotic buying. What is fascinating is that US (Union) government debt rose from $77mm when Lincoln took office in 1861 to over $3.4bn in 1865 – largely financed by government bond sales pushed to investors on the basis it was the patriotic thing to do to preserve the Union.

Somehow, I don’t see much appetite across Europe for saving Brussels on the same patriotic basis. It’s also worth noting that the EU will be launching its new bonds at an interesting moment, with a long-term bear bond market on the horizon. With US consumer price inflation at 2.6%, it’s a clear sign of a developing inflationary bias. That’s hardly a surprise as the global economy prepares for the pandemic reopening, global supply chains remain taught, and fiscal stimulus plans abound.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.