The French are hardly a people noted for their humility. But this week, as Donald Trump visited Paris, the air was particularly thick with self-satisfaction. In Emmanuel Macron, the French have a president who is confident, cultured and popular. In Donald Trump, the Americans have a know-nothing blowhard who can’t even shake someone’s hand without things getting really, really weird.

It fits with a broader theme. A couple of years ago, it was Europe that was the political trauma patient and Britain and America that were the islands of stability. A few referendums and elections later, it is the Anglo-Saxons who are tottering and the Europeans who are feeling distinctly smug about it.

Yet the strains and stresses afflicting the European continent will not be resolved by one election result – or even two, assuming Angela Merkel wins her expected victory in September.

Last month, Oliver Wiseman wrote for CapX about the divisions within and between Europe’s people and elites. And now the latest Authoritarian Populism Index from the Swedish think-tank Timbro has reminded us that the long-term trajectory of European politics is not a good one.

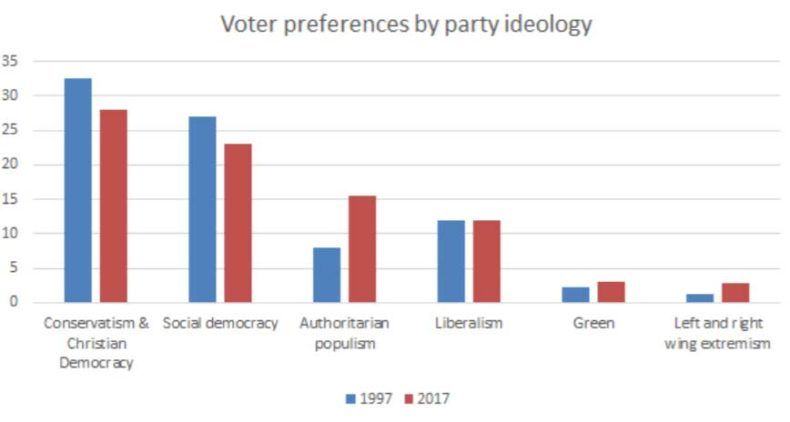

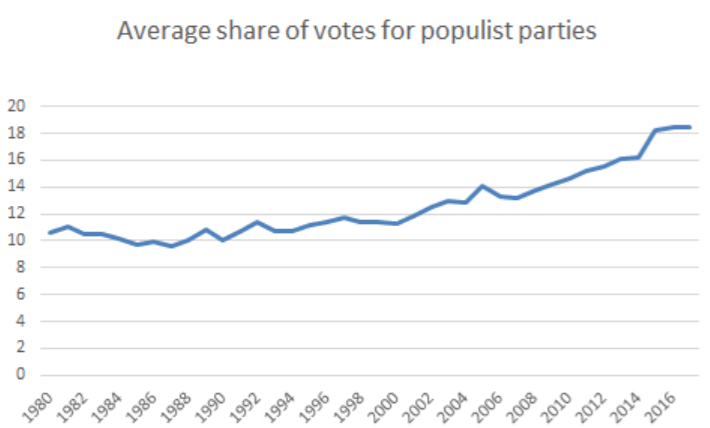

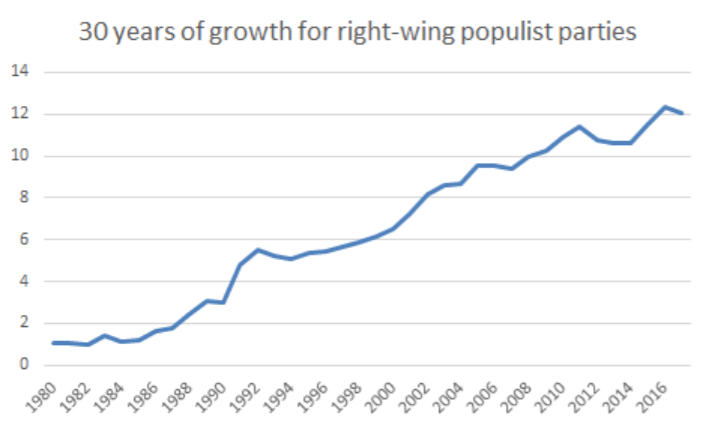

What it finds is that there has been a sustained surge in the popularity not of extremists – fascists and communists – but of “authoritarian populists” who explicitly challenge the post-1945 consensus.

They are defined, says Timbro, by “1) the self-image that they are in conflict with a corrupt and crony elite; 2) a lack of patience with the rule of law; 3) a demand for direct democracy; 4) the pursuit of a more powerful state through police and military on the Right and nationalisation of banks and big corporations on the Left; 5) [being] highly critical of the EU, immigration, globalisation, free trade and Nato; 6) the use of revolutionary language and promises of dramatic change”.

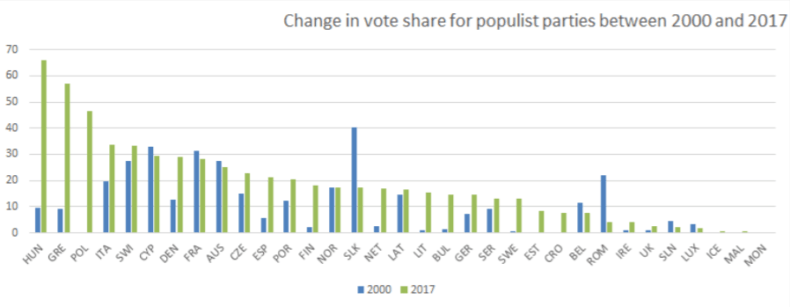

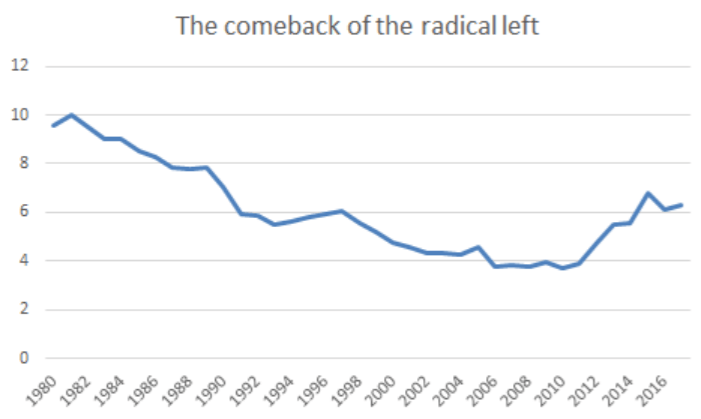

Parties representing these positions were on an upward trajectory even before the financial crisis. In the years since, the tribunes of authoritarian populism have surged in popularity in most European nations, and assumed outright control of several, including Poland and Hungary. In total, 55.8 million Europeans gave them their backing in their most recent national elections.

And it is this – and certainly not Brexit – that poses arguably the greatest challenge to the European order since it was first established. That order rests on consensus, and in particular on the creation of a supranational political infrastructure to regulate, monitor and arbitrate between the competing ideas and interests of its component nation-states. Yes, each country plays the game to its own advantage. But they broadly agree on the rules.

The reason the rise of authoritarianism is such a problem for this system is, like many of the EU’s other problems, down to the idealism (bordering on naivety) of its founders. To gain entry to the club, you had to be a civilised country – to contort your laws and politics into the desired shape.

What nobody ever considered was that countries that had already got their membership cards might then deviate from that blissful end-state – that their democracies might be polluted by populism, racism or gangsterism. Or, indeed, that EU members who had signed away their sovereignty might want to start making their own decisions again.

From the Brussels point of view, Victor Orban (for example) is exactly the kind of barbarian the EU was built to deter. Yet he is not merely at the gates, but inside the halls, banging his fist on the table.

This, of course, has been exacerbated by the Continent’s economic plight. Yes, growth is picking up. But the fundamental problem of the euro has not been solved: there is no interest rate that can suit 19 very different economies without causing wild distortions in some member states. And the only sustainable long-term solution – for there to be a genuine fiscal as well as currency union, probably between a rather smaller number of states than is presently the case – will stir up further political passions. All this before you even start to consider the impact of the migration crisis, or the threat of Islamist terrorism, on domestic opinion.

There is a long tradition, of course, of Anglo-Saxon commentators predicting the cracking-up of Europe. Certainly, we here in Britain, and our cousins in America, are hardly looking the epitome of strength and stability. But the rise of authoritarianism and illiberalism across Europe suggests that its leaders, and citizens, have precious little cause for complacency.

This article is taken from CapX’s Weekly Briefing email. Sign up here.