Europe has its swagger back. The eurozone seems to be putting its economic woes behind it. Emmanuel Macron has just won a legislative landslide to accompany his triumph in France’s presidential election. Populist insurgencies, including those by the PVV in the Netherlands, the AfD in Germany and the Front National in France, seem to be fizzling out. And Theresa May’s electoral humiliation has emboldened Michel Barnier and his team just as the Brexit negotiations finally begin.

The result of all of this is a bullish mood in Brussels. Even a sense in some corners that the challenges the EU faces – not least Brexit, which was initially painted as a devastating blow to the European Project – has inspired a level of continental unity that has been absent for years.

But is Europe really that united? A detailed answer comes in the form of a Chatham House report, published this week, which looks at the attitudes of the European public and elites.

The Future of Europe, by Thomas Raines, Matthew Goodwin and David Cutts, is a reminder that even though the EU has managed to avert disaster lately, there are whopping great questions about its future – and all too little consensus on what the answers to them should be.

Based on polling 10,000 members of the public and 1,800 members of Europe’s “elite” – politicians, businesspeople and journalists – across 10 member states, the report finds three main problems. The gap between Europe’s elites and the public; the growing and increasingly entrenched division within the public between liberals and authoritarians; and the utter lack of consensus among the elites over what direction the EU should be heading in.

In terms of the first problem, the elites and the public don’t just disagree over this or that policy. Only 34 per cent of the public feel they have benefited from their country being part of the EU, compared to 71 per cent of the elite. Most voters think things were better 20 years ago. The elite disagree.

When it comes to the divisions within the public, voters are increasingly clustered at either end of a liberal-authoritarian spectrum – with their views on the European Union tied closely to their position. That means that Europe (like Britain) is split between two increasingly distant and increasingly hostile political tribes.

Of course, this disunity can be overplayed. It would be odd if there weren’t disagreements within any polity over difficult decisions. The European Project can still draw on a well of cross-border solidarity: half of the public think richer member states should provide support for poorer ones, while only 18 per cent disagree. (Though voters in countries such as Germany doubtless have trenchant views on how extensive that support should be.)

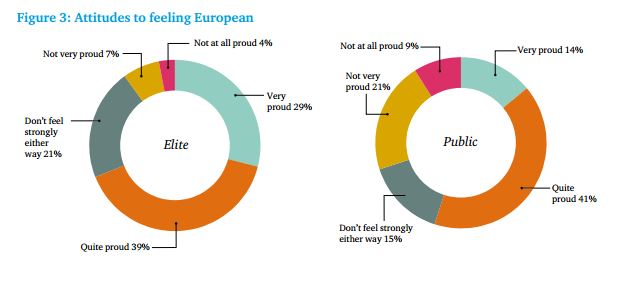

Similarly, when asked about their European identity, 56 per cent of the public and 68 per cent of the elite said they feel either “very” or “quite” proud of being European.

But the wider problem is that there isn’t anything close to consensus among the elites as to the direction Europe should take.

We in Britain tend to believe the EU is inexorably turning into a super-state – and there are certainly those within Brussels and outside it who have devoted themselves to that goal (France’s new president, for example, can’t get enough of federalism).

But even among Europe’s elites, there isn’t any consensus for this. On the contrary, they are divided in a way that all but guarantees inaction: 37 per cent think the EU needs more powers, 31 per cent think some powers should be returned to member states, and 28 per cent support the status quo.

These dividing lines don’t just run along borders. They cut through every level of European society. And they are especially important at a time when the EU faces a long list of threats. One of the report’s most striking findings is that, according to Europe’s elites, Brexit doesn’t even make the top 10.

From a British perspective, the report is also a reminder of just how imperfect both options were in the EU referendum a year ago. In the intervening 52 weeks, we have been reminded time and again of just how risky a decision the Leave vote was. What is forgotten – and what this report inadvertently makes clear – is just how unsatisfactory the alternative would have been.

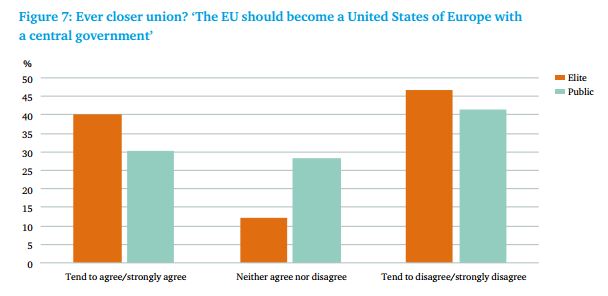

Remaining would have meant the British people casting their lot in with other electorates whose attitudes to the EU – and further integration – they were fundamentally at odds with. When asked whether the EU should become a United States of Europe with a central government, 40 per cent of the elite and 30 per cent of the public agreed. And yes, as the graph below shows, more people disagree than agree with that statement. But that is still a very different situation from in Britain.

In other words, if we’d voted to Remain, we might have found ourselves proceeding down the road towards a federal Europe. Or we might have found ourselves members of an organisation that frequently seems paralysed in the face of the challenges facing it.

As for both the people and the elites of Europe itself, it might seem like the EU has rediscovered its strength and stability. But tackling the obstacles that lie ahead will require more original ideas than are currently in evidence – as well as political leadership that can bridge the divides which this report lays bare.