Muhammad Ali was the greatest. We can say that with a high degree of certainty because he repeatedly told us he was ‘the greatest’ and, as we so regularly do with our celebrities, we believed him. Once he started to tell us about his greatness, we could no longer detach his greatness from his character. Ali became a point of cultural compaction: the embodiment of a socially appropriate egoism attached to superstardom. It remains part of the Ali legacy that modern America, and indeed, much of Western culture, exists in a state of overt but poorly defined ‘greatness’. From Donald Trump to Kanye West, our world is filled with extroverts who proclaim their own genius but have questionable delivery. ‘Make America great again’ might be Trump’s deliberate reminder of Regan’s slogan, but ‘great’ in what respect? That ‘great’ is the very same ‘great’ as found Ali’s ‘greatest’, in that it is defined by something peculiar to the individual. In Trump’s case, it is a greatness based upon of profligate wealth and arbitrary power. In Ali’s case, it was more noble. It was a self-proclaimed greatness that stood in the place of the greatness that white America had refused to grant him. When Ali returned to America after winning the Olympic gold medal in 1960, he was refused service in a cafe in his own home town of Louisville. The legend has him throwing his gold medal in the Ohio River. If his nation would not acknowledge his greatness, he would do that himself and that he did with spectacular results.

It was this genius for self-definition that made him iconic; the giant with a mouth as big and as powerful as his Claymore fists. There was surely no question why people’s wills were bent to his. He attracted the key players of their day to his training camps and he, in turn, became the subject of one of the twentieth century’s greatest pieces of journalism in the form of Norman Mailer’s The Fight (Mailer eulogised the champion, believing ‘a modern Mohammad Ali might become the leader of his people’), as well as what Rolling Stone‘s publisher Jan Wenner called ‘the biggest, f***ed-up journalistic adventure in the history of journalism’. That ‘adventure’ was later relayed by illustrator Ralph Steadman who had accompanied Hunter S. Thompson to cover the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ in Zaire in 1974 only for Thompson to miss the fight (he’d sold the tickets to buy drugs) in favour of lying drunk and stoned in the hotel swimming pool. Ali’s role in this was simply to be Ali. Only somebody as great as Ali could define the scale of Thompson’s insanity.

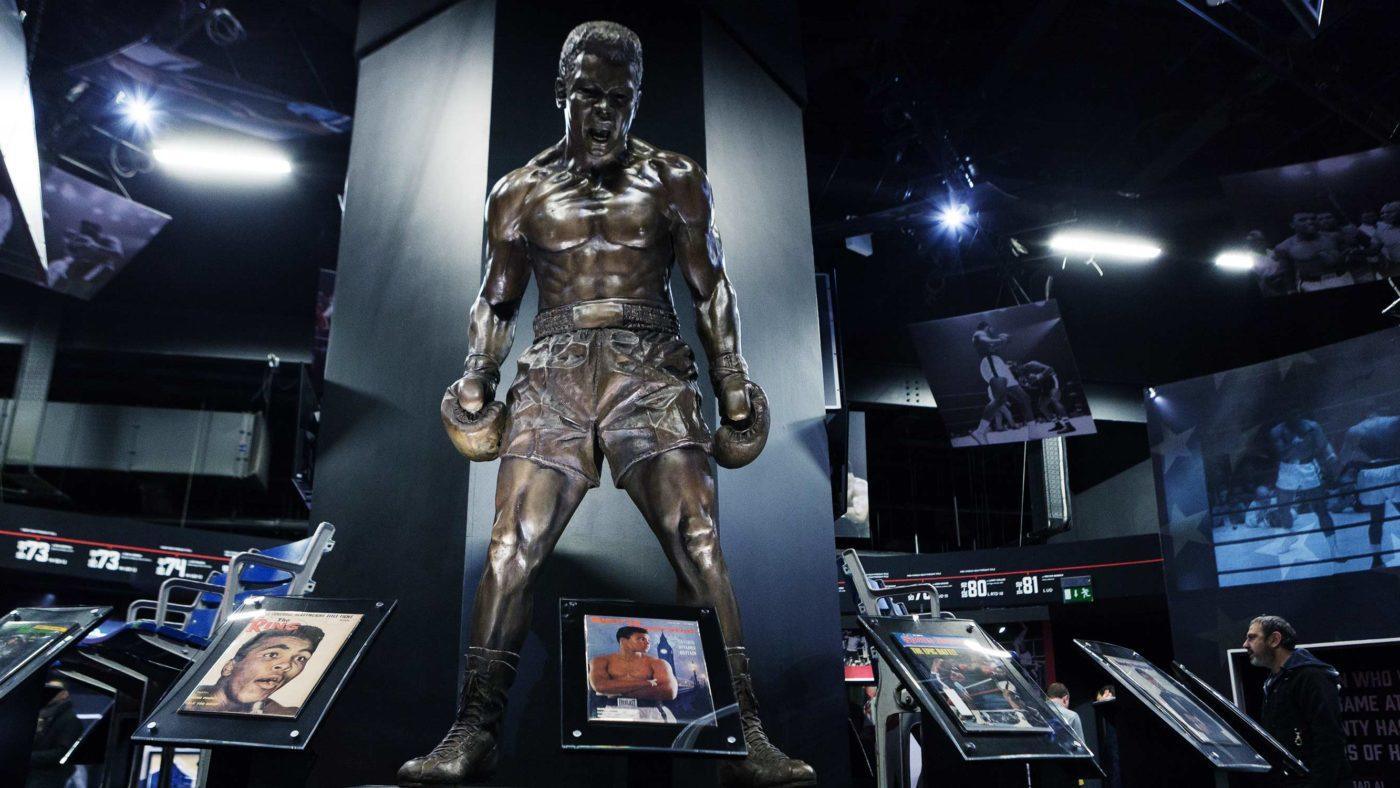

In the wake of Ali’s passing, social media has been buzzing with the memes, the memories, and the tributes. It is all worthy of the man who was three time world champion yet Ali will rightly be remembered for his opposition to the injustices of white America and its role in Vietnam more than his boxing. As the tributes are raised, caps doffed, knees lowered, there is, however, an unmistakable simplification of the truth going on. Piers Morgan was ridiculed on Twitter and castigated in this morning’s press for reminding people that Ali’s story was not a simple story. There was a complicated side to Ali that is too often treated as though it simply did not exist. That was the Ali who espoused the language of black supremacism, who once explained to Michael Parkinson that he believed in the segregation of the races. It was Parkinson who rightly reminded us that Ali was ‘a man of great genius, but was not without his flaws’. Ali once told David Frost that ‘all Jews and gentiles are the devil’.

‘Everything black people do that’s wrong comes from you. Drinking, smoking, prostitution, homosexuality, lying, stealing, gambling. They all come from you.’

What is shocking isn’t that Ali expressed these views but that he was pressed so rarely on them that they did little to damage the gloss of his stardom. Collectively we all looked the other way and we still largely do, whilst, at the same time, castigating another World Champion, Tyson Fury, for similar, if far less eloquent, remarks. Do we do that because Ali was more charismatic and often spoke through a smile? Did the twinkle in his eye excuse his excesses? In some warped version of our logic, do we think that Ali was simply righting some wrong? Wasn’t it only right and welcome that he took pride in his people and his colour? Didn’t Ali balance the centuries of black oppression even if he overstepped the bounds of what many a rational person would consider fair?

All of these, I think, are true but it means that Ali’s greatness sits with a small parenthesised warning that reads something like: ‘might display symptoms of a less enlightened age’. His rapid decline to Parkinson’s meant that he retreated quickly into private life and there were few reassessments of his beliefs in his lifetime. Notice how President Obama said that ‘Ali shook up the world – and the world is better for it’. It was a fine tribute but clever in that it disguised criticism in that ever-so-carefully selected word ‘shook’. Ali was not a simple hero. He was disruptive at a time when American culture needed disrupting. In some muddled way, Ali’s wrongness was a symptom of a cultural wrong and we excused him because, in his limited case, the second wrong did go some way towards making the totality feel right.

In that respect, Ali was unique and it’s that uniqueness we should celebrate. Yet it does his legacy no good to simply gloss over his faults. Ali’s role in the twentieth century was simply too significant. His story is a story of greatness because his character was, like all great characters, ridden with frailties. His relationship with Islam was itself part of a greater narrative of this and the previous century. It was also Ali who made room in the world for a new boastfulness; a brash form of superstardom that now too often lacks his charm, grace, and wit. Ali was the original and, by being original, he managed to carry off an attitude that today has grown stale. Yet a capacity for staleness was also there in Ali. He often promised style but sometimes lacked substance. ‘The people want to see a fight, not a dance’ as Joe Frazier once memorably said to Ali on The Dick Cavett Show.

The ‘Ali shuffle’, the ‘trash talking’, and all the floating butterflies added little to boxing beyond making a sport even more entertaining to the audience it had found in television. Unable to separate his growing fame from diminishing ability, he allowed his career to go on for too long. As early as 1976, he was part of a shameful event in Japan when he shared a ring with a wrestler. The bout is now thought of as a precursor to modern mixed martial arts (itself a questionable accomplishment) but it made for a sad spectacle. Wrestler, Antonio Ioki, spent the entire match on the canvas from where the convoluted rules allowed him to launch savage kicks at Ali’s knees. The ’bout’ ended as a draw but Ali hobbled away on badly injured legs.

It was a minor note in Ali’s long career – he went on to fight more notable opponents before he retired in 1981 – but it was the Japanese exhibition that still feels the most modern: an event promoted beyond its capacity to satisfy. Ali’s posturing has become all too familiar in a sport that is now more memorable for the spectacle around the fights than the brawls themselves. Mixed martial arts is rapidly growing in popularity as boxing struggles to provide the fights in an era of managed hype.

When Ali affirmed his own greatness, he did so in a day and age when self-esteem was a private matter. People were taught humility, often the humility of a working class who were told not to stray or aspire. The great achievement of British conservatism in the late 1970s was to unlock people’s aspirations; its great failure in heralding an age of relativism, in which the ‘greatness’ of the plumber was suddenly a greater ‘greatness’ than, say, the evolutionary biologist, mathematician, or poet.

Is it any wonder we that we find ourselves today without a means to measure greatness? To those in the know, the experts who understand the fight game, Ali earned his place among the true greats of boxing but fell a little short of the very top. He was perhaps the greatest heavyweight (though I find it hard to believe anybody could beat Mike Tyson at his youthful rampaging best) but heavyweight champions are a peculiar breed of fighter. Watching those great ‘Rumbles’ and ‘Thrillers’ now, they are characterised by tired lumbering men stumped on the hard breathing end of slow jabs. In terms of technique, you’d need to look to a lighter man (or at Ali at his peak before television made him a superstar). You would look to Sugar Ray Robinson who, more than any boxer, could claim to have been the best.

Yet Robinson isn’t ‘The Greatest’ or, at least, popular opinion doesn’t rate him that highly. That title belongs to Ali and only to Ali because he was the first (and loudest) to say it on TV. What that ‘greatest’ means is still vague, couched in his personality, his politics, his religion, his rebellion, as much as it is in his athletic prowess. It is, ultimately, the single more memorable expression of self worth. But Ali was always a product of his self and, perhaps, that’s why his life and now his passing are so significant to so many people. He was as much a fiction as he was a fact, an emulated and virtualised person as much as he was flesh and blood, and in that, he was perhaps the very first of us to be truly modern.