Looking at China’s move from a “peaceful rise” to border conflicts with India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Bhutan, Indonesia, Japan, and Pakistan – not to diplomatic conflicts with Canada, Australia, and a new Cold War with America, it struck me – why is China taking on everyone at once?

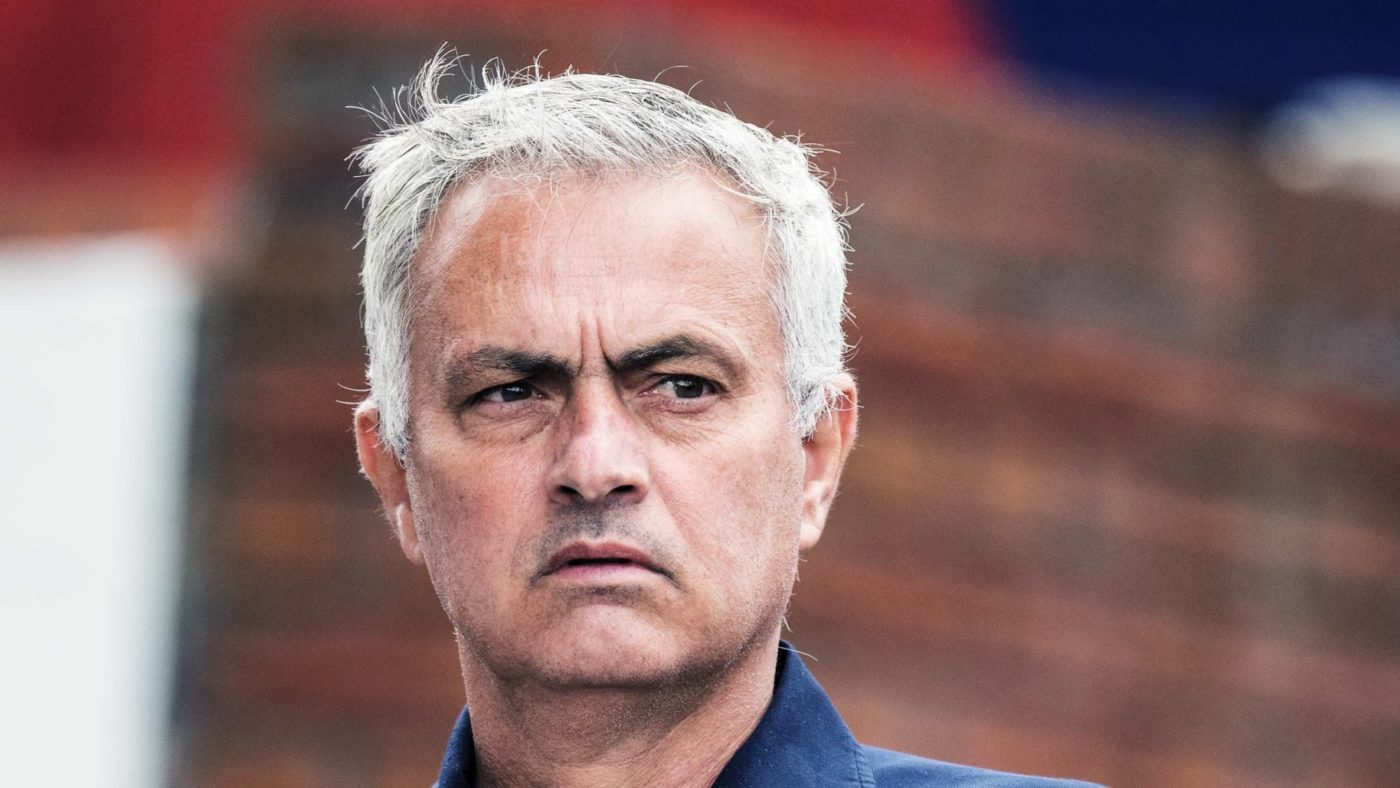

Surely this is the opposite of effective diplomacy, which is about enhancing your capabilities by getting others to buy into your story. So why the multilateral aggression? Let’s look at it through the prism of another leader-as-pugilist: Jose Mourinho.

Mourinho’s key strategy is to create external conflict with everyone going, from other managers to referees to the media and the various governing associations. He usually does this verbally, but he wasn’t above poking Barcelona’s then-assistant manager, Tito Vilanova, in the eye. Heightened external conflicts mean stronger internal cohesion and a willingness to sacrifice oneself for the greater cause. It also conveniently means those inside are less willing to listen to external criticism, even when it seems things are going as smoothly as they once were. Former players like Benni McCarthy, Frank Lampard and Didier Drogba have all said they were willing to run through brick walls for Mourinho.

This is exactly how Xi has been operating in China. With the economy slowing down (from its breakneck 10% a year under Hu Jintao to probably less than 6% before the coronavirus), and the Communist Party facing torrents of criticism from inside China for corruption and cronyism, Xi needed something to hold things together.

Conflict with external parties – the US as an ideological enemy, but also territorial disputes – would serve nicely. There was little prospect of genuine harm, since Western countries were seen as weak-willed (the Great Financial Crisis shook China’s image of the west to the core), and China was already far more powerful than most of its neighbours. And so, fed the idea that their nation was being ganged up on, Chinese citizens grew less inclined to complain about the absence of democracy, or restraints on their access to information, or their extremely limited property rights. External conflict bonded the nation.

Another essential Mourinho tactic is to make himself the focus. He’s the one who puts his head over the parapet, and sets the agenda with the media. This has a dual function. It protects his underlings and absorbs media criticism if things aren’t going so well. But it also sidelines those who are supposed to work with him. He takes all the sunlight and no other trees can grow in his shadow. He has his coterie of trusted advisors, of course, his leading small group with whom his relations go way back, but he is the only sun in that system.

So too with Xi, whose blandly inscrutable countenance adorns almost every cover of the People’s Daily, and who does the travelling and diplomacy (rather than his foreign minister) and leads on the economy (which should be the task of the premier, Li Keqiang). He has his trusty cronies, like Li Qiang and Li Xi (no relation) and has ensured they get high-level positions, but no-one else gets the time to shine. The spotlight is all on Xi, and that’s how he wants it.

Maybe the best interesting parallel is that these strategies worked well when both of them were on the way up. But you can’t play the underdog when you are the manager of Real Madrid and Manchester United, or when you preside over maybe the world’s largest economy. Fighting against the established order can be an attractive proposition, but these behaviours make you look an arrogant bully when you are the top dog. Going out and claiming the entire South China Sea and upsetting Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Brunei might even be courageous if you were a plucky upstart. When your foreign minister dismissed them as “small countries, and that’s a fact” it seems like you’re following the “might is right” playbook of fascism.

Similarly, Mourinho’s counter-attacking play was marvellously effective at Porto and Inter Milan (where he won won a semi-final against Barcelona with just 24% possession in the away leg), but at Real Madrid and Manchester United teams are expected to dominate and play open, attacking football. The Mourinho style didn’t play so well there, though he still won numerous trophies. But the matter was more one of style. Attacking outsiders from the apex of the football pyramid looks like arrogant bullying. When you’re top of the pile, others expect a sort of benevolence. (Jurgen Klopp is very good at this). But being king of the castle and always punching down is not a good look, whether for Xi or Mourinho.

There’s also the undoubted fact that it’s easier to knock the old order down, but it’s much harder to stay on top. The endless conflict that enraptures can only last for so long. People tire and want stability. There have been occasional coded suggestions from inside China that the “wolf diplomacy” adopted under Xi is unpopular and ineffective, while his anti-corruption campaign has made the Chinese Communist Party an austere, monastic experience, certainly in comparison with the anything-goes money-to-burn Hu Jintao era.

And so Mourinho is finding: the old master whose ploys and strategies aren’t quite as effective as before. Fewer players seem to want to run through brick walls for him. The lethal efficiency of his earlier days seems to be slowly fading. The endless conflict that he relies on doesn’t quite burn the fires as they once did.

The comparison has its limits, of course. Xi is a lot more certain of his position since he removed term limits, while Mourinho – like all top managers – could be sacked at any time by his chairman. But both men understand power, and its vicissitudes.

Both men also had fathers who were dismissed at formative times in their lives. Mourinho’s father was sacked as manager of Rio Ave on Christmas Day, while Xi famously had to live in a cave in rural Henan province when his father, Xi Zhongxun, was purged in the early 1960s. Both men thus crave control, and see life as ceaseless conflict. This has brought both men huge success, but the signs are that as a strategy its effect is diminishing.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.