There are wide and far-reaching issues behind the fall of the stock exchange in recent weeks and the drop in business confidence in China.

Initially, SOEs and politicians took Xi Jinping’s reform drive lightly.

A recent commentary in the People’s Daily hinted at this, underscoring that “the uncanny, complex, ferocious, and stubborn (ways) of the forces opposing the reforms possibly exceeded what people imagined.”

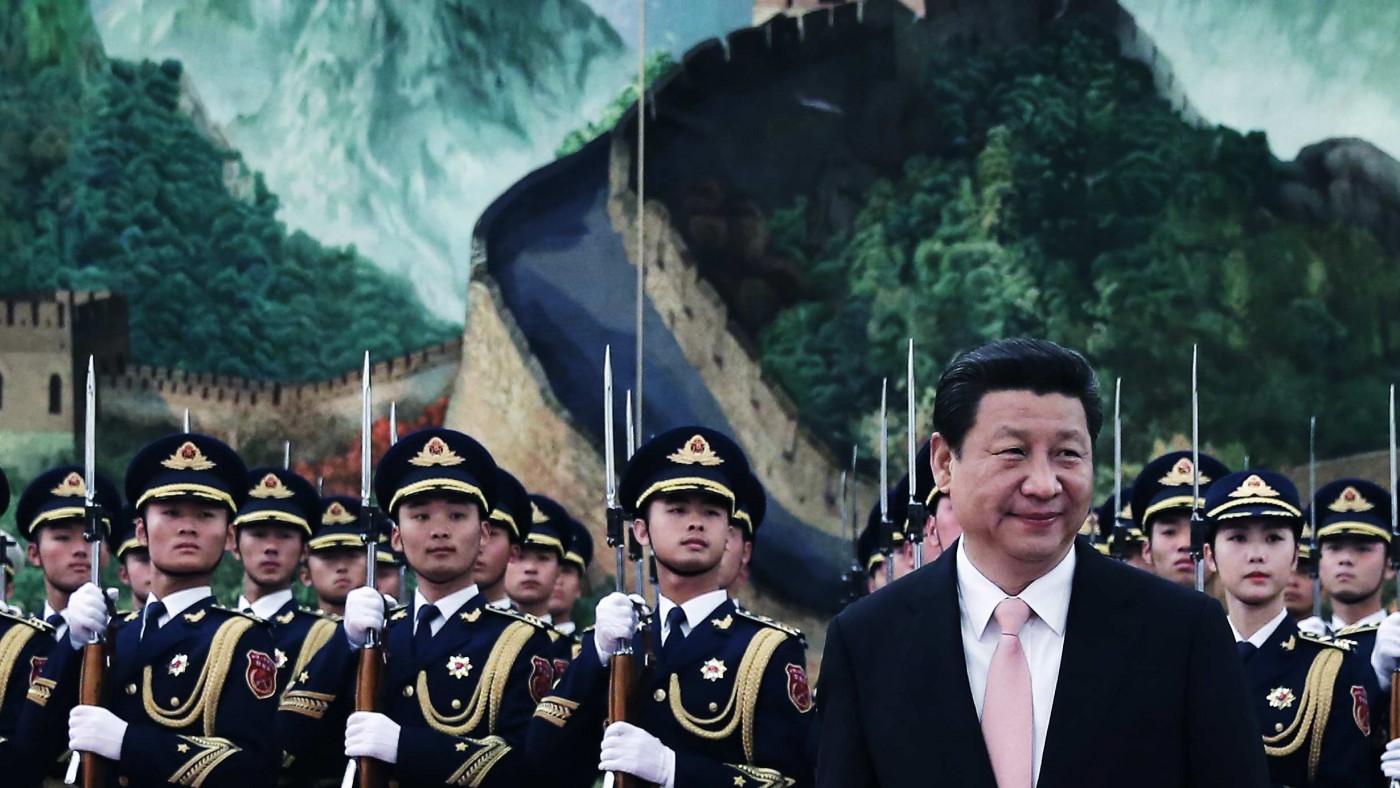

This recent process of reform so bitterly opposed was started because of an economic analysis. In a nutshell, President Xi Jinping and his people realized they had to put a stop to the action of the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that were disrupting the economy and thus endangering the long-term well-being of the country.

The SOEs could marshal trillions of RMB to advance their own particular interests and hijack the policies and interests of the country by directly or indirectly influencing leaders and political decisions. They could do that for two reasons: They could dispose of the cash flow without any real checks from national and party institutions; and they had privileged access to finance, which they then could distribute at a premium to private companies that were and are the main force of development for China.

In other words, if one could restrain and slowly shrink the role of SOEs in the Chinese economy, the government could indirectly help private companies get easier access to cheaper money (with cheaper interest rates from banks), check the unfair competition of SOEs against private companies, and clean up the political atmosphere of the nation overall allowing politics to think more freely about its direction. Just for these reasons, SOEs and politicians linked to SOEs are bitterly opposed to these reforms, which would deprive them of power and enormous amounts of money.

Possibly at first, these SOEs and politicians underestimated the latitude and determination of Xi Jinping’s reforms. They possibly might have thought that his anti-corruption campaign was some kind of window dressing, and after a few months, things would go back to the old ways; or they thought the reforms would never end up touching the former top echelons of the party. However, Xi has proved he is genuine and wants to change the economy and the state of China. This is what he is doing now.

The problem is that after decades, SOEs and private enterprises often are an almost integrated body. SOEs and officials have groups of private entrepreneurs behind them, so when the anti-corruption campaign hits SOEs and officials, private entrepreneurs linked to them are also scared of being dragged into the crackdown. They are, therefore, growingly timid and scared of the economic climate in China: The old way of doing business is gone, and for them it is not clear what the new way is or should be.

Here the problem gets extremely complicated because officials, who were active in supporting business, expected to get money in return. Now without their old incentives, officials just drag their feet and are not interested. For this reason, Xi is pressing officials to become proactive again, arguing that during their tenure they have to show some economic results, otherwise they will be dismissed. There is, therefore, the fear of punishment that should force them to be pro-active. Nobody knows how and if this negative spur will work, and certainly this goes against the grain of the business culture that has grown very strong in the past 40 years or so.

The risk in all of this is that the economy will be dragged down. Perhaps to try to jump-start it and to try to get the best and healthiest SOEs on the side of the reforms, the government encouraged the growth of the stock exchange, which took place at the beginning of this year. Unfortunately, as we saw, the stock exchange in China was not cleaned up beforehand.

SOEs went back to their old practice of insider trading, and in addition an underground shadow banking system abused the new financial instrument of “margin calls” to artificially boost the market. When authorities started investigating shadow banks’ activities in the market at the beginning of the summer, investors fled, driving the whole index down.

The first crash of the stock exchange was perhaps also meant to scare Xi Jinping, hinting to him that if he did not stop his anti-corruption campaign, there were forces in China determined to create havoc. Xi was undeterred, and as a result, investors grew even more timid, and we are now at a crucial juncture in the process.

Certainly, economic growth in China is still strong enough to withstand any short-term turbulence in the stock market. Surely, the new weakening of the RMB will in time help the healthy growth of private entrepreneurs who make up about 80 percent of all Chinese exports and who will hence benefit first from the recent devaluation. However, the recent editorial points at larger problems: How to root out the enemies of reform and how to restart the economy by giving confidence to some of the old and new entrepreneurs in China.

In a way, the order of actions should be clear, and at this stage it could be dangerous for Xi Jinping and his reforms to boost the confidence of entrepreneurs who might still have links with the old regime and its corrupt officials. Therefore, it may be necessary to first make sure that old corrupt officials are never again in a position to harm the business environment of China with their interference. This seems to be the argument of the recent commentary in People’s Daily. We do not know how far Xi is willing to go, but he definitely seems extremely determined to carry out his new policies and there is no time limit for the end of the anti-corruption campaign.

In any case, besides the negative, repressive measures, China eventually also needs some positive actions to encourage the growth of a healthy business environment, and these perhaps go hand-in-hand with passing some kind of amnesty for past economic crimes, which would put at ease businessmen who have grown wealthy in the past decades and who definitely have skeletons in the closets.

Moreover, this is also necessary because private businessmen have to be the backbone, both financially and managerially, of the privatization of the SOEs, which will be necessary to pay off the huge amounts of debt the SOEs and local governments have accumulated during the years of free-wheeling finance starting after 2008 to offset the American financial crisis. The scope and technicalities of the amnesty will be extremely sensitive.

Would the government allow a simple whitewash of all past crimes, or will it set some limits: say, tax evasion would be forgiven but not other crimes? Will they allow some kind of repatriation shield to let Chinese businessmen repatriate the hundreds of billions they have taken abroad in return for a small fine? What legal guarantees will the state grant to future private entrepreneurs who will come to dominate the economy? And so on.

Moreover, there is a bigger political issue here, which is the political feasibility of amnesty for economic crimes. Such an amnesty would de facto reward daring and ruthless entrepreneurs who defied the law and got away with it. It would punish law-abiding citizens who followed the norms, and would unjustly condemn and forget the business people who in the past were caught and put in prison because of their illegal economic activities.

There is also another angle to this. Some Chinese intellectuals are starting to argue that what took place over the past 40 years in China was a revolution which, as Mao said, is not a tea party. At the end of the revolution, somebody becomes a high official, many are dead, and most of the timorous population that just followed the rules are left at the bottom of the pile. It happened with the Communist revolution in 1949, and it has happened now. These entrepreneurs, who emerged from this 40-year period of wild growth, may not be the most ethical men. However, they are the ones who drove Chinese development.

What is most important perhaps is not forgiving past crimes but setting new rules for the right and legal business activities, making sure that these rules will be observed and create a healthy economic environment for China and for the rest of the world, which is growing linked with China’s development.

This new legal framework for business activities perhaps is the most important thing. Many of these entrepreneurs may deserve amnesty because of their contribution to the country’s expansion and in consideration of the special economic circumstances in which they grew. However, they cannot go on managing their businesses and their companies in the murky, nontransparent dictatorial way many of them have adopted so far.

Even private companies have a state and societal responsibility to employees and investors. Yet, so far, most of these responsibilities have been widely ignored and dismissed in Chinese private companies. Therefore in return for amnesty, these companies have to strictly abide by new rules of transparency and governance, or they should be put out of business. It is a long and complex task ahead for Xi Jinping and his people.

In the short term, it should be important to suggest the future outline of the society the government envisions to give new confidence to the market in China and in the world, which has grown so worried about China’s economic performance in the past weeks.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, China managed to greatly contribute to push the world out of the financial crisis and has been in the past years the single largest element of economic growth at a global level. Therefore, whatever it does hugely impacts all markets, which then can create a mirror effect in China: Chinese markets get scared, then they fall; the world markets see China fall, and they fall; China sees the world markets fall, and it falls even further; and this leads to a spiral.

The spiral must be stopped and in a way Xi Jinping now has the great opportunity to emerge not only as the leader of a new China but also as an important stakeholder in the leadership of the world.

This article was originally published in the Asia Times, and can be read here.