Bizarrely, the front-line debate on the economics of leaving the EU now centres on whether Britain should stay or remain within the EU’s customs union. This is bizarre because, unlike with the single market, Brexiteers of all stripes took the departure from this customs union as given and a boon.

By definition, a customs union is an agreement between countries to embrace tariff-free trade between members but impose common tariffs on goods imported from non-members. At an EU-level, this means a Common External Tariff (CET), a dizzying array of over 12,651 different taxes (and some quotas to boot) imposed on goods from the rest of the world. The long and short of it is that the EU is internally trade liberating but outwardly protectionist.

The argument for remaining a member of this block (as articulated by the UK Chancellor Philip Hammond) seems to be concern at the impact leaving might have on “complex pan-European supply chains where often components and self-assemblies move backwards and forwards across European borders several times”.

That’s because outside of the customs union, and in the absence of a bilateral free-trade deal with the EU, UK exporters would face the EU’s common external tariff and importers would face the UK’s decided tariff rates under WTO rules (applied equally to EU imports). In other words, businesses could face two-way tariffs if they import and export simultaneously.

This is certainly a possibility. But the degree of disruption is dependent on the Government’s own policy decision on tariff rates. In my view, the case for remaining in the customs union is overwhelmed by the advantages and opportunities from leaving.

After leaving, the UK would be able to set its own import tariffs to prevent the hike in input prices. Most UK Brexiteers desire a free-trade agreement with the EU. In the absence of such a thing, the UK would set its own tariff structures, applied to all countries as per WTO rules.

Any new tariffs faced by those importing inputs from the EU post-Brexit would therefore be self-inflicted, decided by the UK government. The UK Government is perfectly at liberty to abolish tariffs entirely, allowing manufacturing industries to import inputs more cheaply from anywhere in the world.

Exiting the customs union likewise grants the UK the opportunity to lower prices for consumers more broadly and to improve the productive capacity of the economy. The CET, coupled with non-tariff barriers imposed by the EU, has resulted in agricultural and manufactured goods prices being around 20 per cent above world prices.

Such protectionism also distorts the economy away from trading according to its comparative advantages. Leaving the customs union would allow tariff cuts or even give us the opportunity to embrace unilateral free trade.

This would act like a big dynamic tax cut through the economy – lowering goods prices directly, but also leading to more efficient industry as all face competition at world prices. If there were “disruption”, it would be positive disruption leading to a more productive economy.

Using the language of the referendum, leaving the customs union is the only way to fully “take back control” of trade policy too.

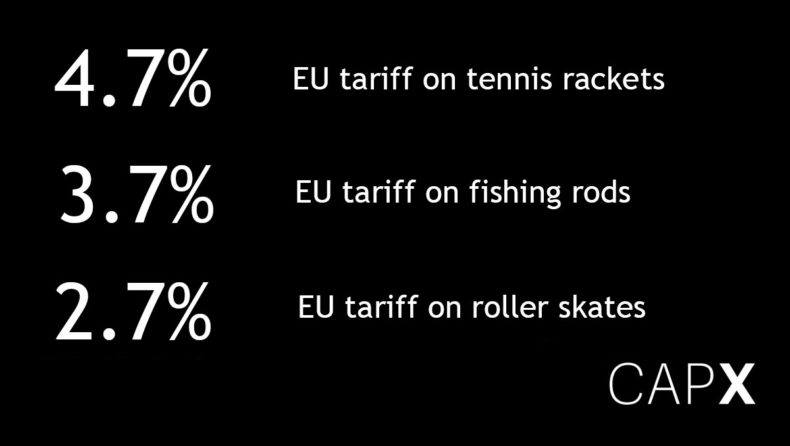

When one looks at the sorts of tariffs the EU imposes (4.7 per cent on tennis rackets, 2.7 per cent on roller skates, 3.7 per cent on fishing rods), one has to wonder: how are these tariffs being decided and by whom? Certainly, they are not for the benefit of the UK’s consumers.

This is particularly obvious when one sees certain tariffs, like those on oranges, applied seasonally as protection against the South African harvest. Quotas on meat carcasses lead to questions about what factors are affecting these decisions on amounts and why. The most credible explanation seems to be overt protectionism, the price of which is paid by UK shoppers.

Exiting the customs union would, therefore, allow the UK to decide tariff policy in a less opaque manner. Even if it were deemed appropriate to “protect” certain industries (a path I would not advocate), the UK would surely cease imposing seven different tariff rates on coffee, a product for which it has no producer interests.

Remaining within the block would mean the UK had no say on tariff rates, despite suffering the consequences of their imposition.

Finally, remaining a member of the EU customs union would severely hamper the ability to sign free trade deals with other countries too. Contrary to popular belief, the customs union in itself does not preclude Britain signing free trade deals (the EU’s common commercial policy does). But without being able to offer up tariff-free deals to third parties, continued membership would in reality severely limit the UK’s leverage and attractiveness for trade agreements.

Since the EU referendum, many politicians in large economies, including the United States and Australia, have expressed desire for striking free-trade deals with the UK. Dealing with the competing interests of 28 different member states, the EU has until now been relatively poor at securing comprehensive trade deals with some of the world’s largest economies. Leaving the EU enables the UK to be nimbler in making deals.

Yet if she cannot offer reduced-tariff access to her markets in goods, it is unlikely that trade negotiators will grant the UK better access in services in the negotiator’s own markets. This tit-for-tat mercantilism is regrettable, but a well-known feature of trade deals worldwide.

All this is not to say that leaving the customs union will not lead to some costs for certain firms and industries, or disruption. There will be more in the way of customs checks (though these would likely quickly become routinised). But the aggregate benefits of a UK controlling its own trade and tariff policy, particularly for consumers, are likely to be much greater.