This series of articles began long before Theresa May announced her resignation. Now that the Tory leadership contest is well and truly underway, it is clear one of the key battlegrounds will be who is best placed to remake the case for the market. In Boris Johnsons’ words, who can extoll “the merits of free-market capitalism”?

The surprising return of socialism to the top of the Labour party has left many on the right shell-shocked and bewildered at how a debate they thought they’d won in the 80s has re-emerged. And for those that have waded into the debate once more too, the virtues of free trade and capitalism are too often presented in theoretical terms. Worse, some present capitalism not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself.

But this theoretical absolutism does nothing to challenge the conclusion many people have arrived at, which is that free trade, globalization and capitalism have resulted in an unjust, unfair and inequitable allocation of resources.

Globalization has been defined by the outsourcing of production to lower cost and lower income countries (such as China, Vietnam and Thailand) while middle- and higher-income countries have become increasingly service-orientated economies. There are some anomalies: Germany has a thriving manufacturing industry, for example.

In Britain, the loss of manufacturing jobs coincided with an explosion of wealth created in the financial services industry (geographically focussed in London) which drove inequality higher in the 1980s. The popular resentment towards capitalism in Britain is partly down to this confluence of factors. Theoretically, free trade and capitalism may be good at efficiently allocating resources and boosting production, but practically many feel that they have only witnessed the disappearance of blue-collar jobs that delivered identity and dignity.

So, this final article in a series on ‘the rights record on poverty’ targets this inaccuracy. It makes the case for capitalism, free trade and globalization in terms of what it has achieved for the poorest in our society. Using data not theory, it becomes clear that the era of hyper-globalisation (which began in the 1980s) has done huge amounts to lift living standards and reduce poverty in Britain.

Wages, Jobs, GDP and Poverty

The late 20th century was largely defined by exponential increases in global trade, technological advancement and an expanded role for the role markets in our economic system.

Between 1960 and 2017, total global trade in goods increased form $130bn to $17.7trn. In 2017 total trade in services also came to $5.5trn. The UK has been at the centre of this global economic revolution. In 1961 we exported just £4b in goods, this grew to £80bn in 1988 and reached £350bn in 2018. In services the UK exported £1.4bn in 1961, £30bn in 1988, and £283bn in 2018. Up until the mid-80s the UK maintained a neutral trade balance, however since then import growth has driven record trade deficits. In 2017 we imported £102bn more than we exported.

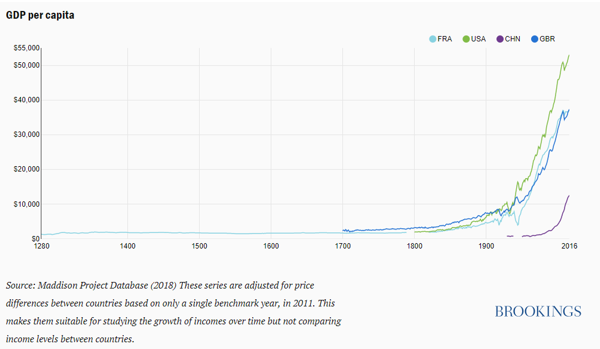

Why is this relevant? Because it spurred an unprecedented period of investment and growth for the economy that has delivered for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged in Britain. The economy has quadrupled in size since the mid-60s. More than 8 million new jobs have been created.

These jobs are also better paid; in 1970, a male worker could expect to take home just £455 per week in 2018/19 terms, (a female worker could shockingly expect half of that), today it would be closer to £721 (and the gender pay gap is closing). More of those jobs are ‘highly skilled’, safe and with perks; higher skilled occupations now make up nearly half of the total workforce, whereas as low skilled clerical work will soon take up less than a third.

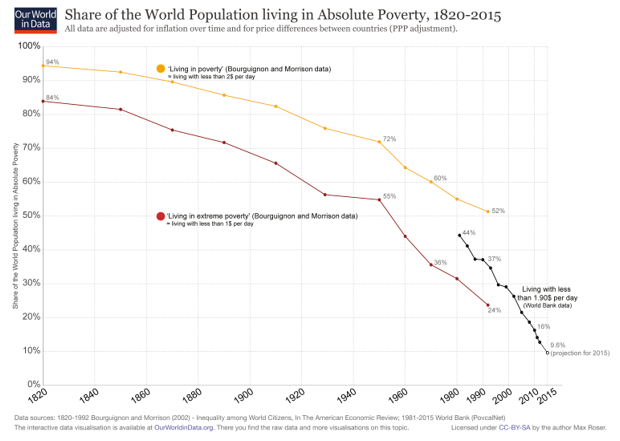

Between the early 19th century and the period after the second world war, global extreme poverty rates had declined by approximately a third. Between the early 80s and today extreme poverty has declined by approximately 80 per cent.

The acceleration in the decline of global poverty was largely driven by growth in Asian and Latin American economies. However there have been significant reductions in prevalence of poverty in Western economies, including here in Britain. Studying absolute poverty rates, the proportion of the population in absolute poverty (measured as 60 per cent of the 1996/7 median wage) has fallen from 66 per cent in 1961 to 27 per cent in 1988 and to just 11 per cent in 2018.

However, some claim that capitalism and free trade have caused stagnation in wages for the lower middle class of higher income economies between 1988 and 2008, an idea popularised by Christoph Lakner’s ‘Elephant Curve’.

Analysts at the Resolution Foundation, however dispute this, and claim that when you tidy up the data (controlling for country selection and dropping the consistent anomaly that is Japan) you see that the entire income spectrum in the UK has done well in the period. In fact, the bottom decile of earners in Britain has performed better than most other countries.

There is of course no doubt that inequality remains a problem in western economies. However, while Britain saw a significant increase in inequality in the 1980s, IFS data shows that in the periods before and after, income growth for earners at the 20th percentile kept up with the richest at the 80th percentile. Between 1961 and 1979, real income growth (after housing costs) for the 20th percentile grew by 37 per cent, while at the 80th percentile it grew by 44 per cent. Between 1990 and 2018, real income growth at the 20h percentile was 60 per cent, while at the 80th percentile it was 50 per cent.

The notion that globalization and capitalism have driven wage stagnation for the poorest in the West is not backed up by the data.

The post-80s era of hyper-globalisation and free markets hasn’t just helped to deliver jobs and wages for the most vulnerable in Britain. A larger economy has also boosted tax receipts which in turn has helped create the compassionate social security net that we have today. Public Sector current receipts grew from £9b in 1961 to £753b in 2018 (although tax rates are lower).

As a result, spending has increased in line with income. Total Government spending in 1961 was approximately £10bn, by 1980 it was over £100bn, in 2019 it will be more than £800bn. In the early 80s, the UK spent approximately 4 per cent of national income on healthcare (approximately £40bn in 2017/18 prices). Today those figures are 7 per cent of national income, and more than £150bn. In the 1980/81, the UK spent £74.9bn (in 2015/16 prices) on social security. By 2015/16 this increased to over £217bn. All of this has helped drive lower poverty rates. According to data from the IFS, the number of people in poverty has halved since the late 90s.

Life, Death and Human Necessities

Free trade, capitalism and globalisation haven’t just helped increase economic opportunity. They have also helped deliver a vastly better and safer quality of life for many. Life expectancy in the UK has increased by 10 years since the 1960s. Infant mortality rates have collapsed. Better standards of food production, the use of technology in agriculture, as well as the proliferation of safe preservatives have helped people live healthier and longer lives.

Of course, some would say these improvements are more than just a function of economic systems. However, compare the UK to a closed economy that hasn’t got free trade, capitalism and enterprise – Venezuela. The South American country has a life expectancy 5 years lower than the UK (North Korea is 10 years lower) and very high child mortality rates; “Infant mortality in Venezuela reached 21 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2016, according to the study, a rate not seen there since the 1990s. That’s well above the average 15 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2017 for Latin America and the Caribbean”.

The Venezuelan murder rate is 81.4 homicides per 100,000 people. In 2018, Venezuela tallied 23,047 violent deaths, 10,422 of which were homicides. This is expected to be the highest, ahead of El Salvador and Honduras. US homicide rate is about 5 while the UK is at just 1.2.

It is also worth pointing out that conflict-related deaths have declined as capitalism and trade have increased. Deaths as a result of conflict have fallen since the end of the second world war, only for a spike to occur as a result of the tragic Syrian civil war. Alistair Heath explains why “It is often wrongly argued that armed conflicts are the handmaiden of capitalism; in reality, they are the worst thing that can happen to a liberal economy, destroying lives, families and capital and triggering state control, militarism and deglobalisation.”

Material Advancement

Markets have delivered huge advancements in our material wealth. Jesse Norman, writing in the recently released book from the Centre for Policy Studies Britain Beyond Brexit, highlighted how markets, competition and innovation have, over time, improved and enhanced the most basic practice of written communication; “Today markets changes are often driven by shifts in technology. Take the capacity to communicate in writing: thousands of years ago, hominids could draw on sand with their hands or with sticks, or scratch marks on stone; then came stylus and ink on papyrus, quill pens, pencils, the fountain pen, the ball point pen, the typewriter, the desk printer, the keyboard, the keypad, predictive text and automatic speech recognition”.

This technological and material evolution has triggered an unprecedented era of consumer choice. In real terms consumers in Britain spend over £1.2tn every year. This is roughly 50 per cent more than just 20 years ago. In 1997 per household spending on good and services was £10,290, in 2018 it was more than double that at £19,985 (and this does not take account of all the digital services we consume but do not pay for).

More households now enjoy goods and services that were once the preserve of the rich; car ownership has increased from less than 50 per cent in the 60s to almost 80 per cent of households today. Now one in three households in the bottom income decile have a car/van. There are seven times more cars on the road in the UK today than there were in 1950. People are taking to the skies more often too, there were 195,000 landings and take-offs from British airports in 1951. However, there were 2.3 million landings and take-offs in Britain over 2017. Over that same period, the total number of passengers that arrived or departed from British airports has increased from 2.1 million (in 1951) to 95 million (in 1991) to 284 million in 2017. In 1997, just 16 per cent of the population owned a mobile phone, now it is closer to 95 per cent. In 1997 just 9 per cent of households had internet access, now it is 90 per cent.

Britain’s poorest have benefited from these goods and services becoming ubiquitous. A lot of things do cost more in real terms today than they did in the late 50s and early 60s. And while the budgets of the poorest have been hit hard by increasingly high housing costs, there is no doubt that material advancement has been facilitated by trade, globalization, and free enterprise.

The Environment

It is often argued that our own material advancements – more cars, international travel, increased consumption of electricity and the mass production non-degradable plastic products – proves capitalism and environmental preservation are mutually exclusive. Former adviser to Nick Clegg and Brookings scholar Richard Reeves said that “Capitalism doesn’t care about the climate crisis, but it is not supposed to. Blaming capitalism for climate change is like blaming distilleries for drunk driving”.

But history just doesn’t back this up. Mark Littlewood in the Times recently showed this, “Communist eastern European governments oversaw an environmental catastrophe. In the late 1980s, as communism entered its death throes, particulate air pollution was 13 times worse in Warsaw Pact countries than it was in western Europe. Gaseous air pollution was twice as high and wastewater pollution three times as high. In East Germany, 60 per cent of the population suffered from respiratory illnesses. Nearly half of all children in Leningrad had intestinal disorders because of contaminated water.… In Venezuela, the Maduro regime has opened up more than 100,000 sq km to mining. This amounts to about 12 per cent of the country’s land mass, including rich tropical forests, as well as the Orinoco and Caroni river basins”.

In the UK, total carbon emissions have fallen to their lowest level since 1890. In London, overall air pollution of particulate matter has fallen by 98 per cent over the same time period. In the United States, CO2 emissions are now at their lowest level per capita since the early 1960s. Even the global picture is positive, “In 1900, one person in 550 globally would die from air pollution every year, an annual risk of dying of 0.18pc. Today, that risk has fallen to 0.04 pc, or one in 2,500; by 2050, it is expected to have collapsed to 0.02pc, or one in 5,000. Many other kinds of pollution are also in decline, of course, but this shift is the most powerful”.

Why is this relevant to the most disadvantaged in society? Because it is the poorest who are most likely to suffer from air pollution and environmental damage. The World Health Organisation said in 2018 that “Poverty can compound the damaging health effects of air pollution, by limiting access to information, treatment and other health care resources”.

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds are already more likely to be at risk of poor health outcomes, while air pollution has been shown to increase the risk of both reduced lung capacity and anxiety. Simply put, creating a cleaner environment is good for helping the most disadvantaged in society live a healthy and prosperous life, and free economies are synonymous with cleaner environments.

Conclusion

The data is clear, free trade, enterprise and capitalism have helped pull billions out of poverty across the globe and improve the lives of millions of the most disadvantaged here in Britain. It has made more jobs available that pay higher wages.

Markets have helped drive down mortality rates by supplying us with medicines, healthy food, and other basic necessities that keep humans healthy. Someone born poor in Britain will generally be healthier and live longer than at any time in history. While housing is more expensive, other material goods have become more available for the poorest in Britain; car ownership, mobile phones, internet access and even international travel.

But while a rising tide has lifted all boats, that has not allayed concerns about inequality.

Inequality remains higher today than it did before the era of hyper-globalization began in the 1980s. While wages of the highest earners dipped in the aftermath of the 2008/09 recession, asset price inflation has helped the asset owning classes become much wealthier. Combine this with recent decline in rates of home ownership and it is less surprising that capitalism is perceived to be a system that is rigged in favour of the already rich.

In 2016, a YouGov survey found more people felt favourably towards socialism than capitalism, and more people felt unfavourably towards capitalism than felt favourably towards it (which was not the case for socialism). The success of Jeremy Corbyn is a function of this.

Richard Reeves rightly reflects that capitalism only works when the people are confident that it will continue to provide improvements in our living standards: “If the promise of a better future starts to fade, a vicious cycle sets in. Why save? Why sacrifice? Why stick at education for longer? If doubt creeps in, people may work less, learn less, save less – and if they do that, growth will indeed slow, fulfilling their own prophecies. The biggest threat to capitalism is not socialism. It is pessimism”.

The purpose of this series has been to use data to prove that right-of-centre policies have really delivered for the poorest in Britain.

In this article data has again proved that capitalism and free trade, contrary to what Jeremy Corbyn would say, has and continues to deliver safer, healthier, more prosperous lives for millions.

The argument for capitalism should be made in terms of what it has achieved, not simply why it is theoretically justifiable. Considering the economy has grown by a factor of four in the last 60 years, winning this debate could be a matter of £6trn in GDP growth over the next 60 years.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.