The importance of a good education in improving life outcomes cannot be overstated. A good school, passionate teachers and inspiration in the classroom can break the cycle of inter-generational poverty that is still all too common in Britain.

For a child growing up in a low-income household and neighbourhood, with a single workless parent, exposed to crime or drug abuse, the probability of repeating their parents’ story is too high. A school is the best chance of intervention and correction; early in a child’s life and outside of the home.

The Economic and Social Research Council recently said, “Education is often used by people to shape their ‘social identity’, framing their understanding of themselves and their relationships with other people. A positive, affirming social identity is associated with a range of positive outcomes in life, such as increased well-being, health, social trust and political engagement”.

The economic value of a good education is equally important – there is clear evidence that incremental increases in each level of educational attainment are associated with higher earnings later in life.

The Coalition years and the Gove reforms

Back in 2010, the Coalition Agreement announced promised “to give greater powers to parents and pupils to choose a good school” and, among other things, to ensure “robust standards”. It laid out a raft of significant reforms to the way schools were set up and run in Britain, the curriculum, support for disadvantaged students, as well as a new means of measuring student attainment.

The best-known reform introduced in the early Coalition years was the arrival of Free Schools and the expansion of the number of Academies. The policy was rooted in the principle that giving teachers and parents more control over a school (specifically its budget and curriculum) increases the opportunities for innovation and competition.

Prior to the 2010 General Election there were 203 Academies in England. There were a further 598 schools converted to academies in 2010/11, as well as 24 new Free Schools. By 2015 there were over 4,500 Academies, today there are over 7,000 Academies and Free Schools, approximately a third of all state-funded schools that taught nearly half of all students in the UK.

One of the more ambitious types of academy that were introduced were University Technical Colleges, serving students aged 14-19. The brainchild of former Education Secretary Lord Ken Baker, UTCs were the first real answer to the UK’s longstanding problem of substandard vocational and technical education.

While Germany, the Netherlands and other more productive advanced economies have a strong technical offer, many felt Britain’s education system was monotone, focusing too heavily on ‘traditional’ classroom-based subjects.

UTCs had to offer students EBacc subjects, but they also offered courses in areas such as engineering, graphic design and health technology. There are currently 49 UTCs in the UK.

Outside of school reform, one of the most significant recent changes has been the emphasis on teaching children to read using phonics (learning how letters sound and decoding words from there). From 2012 teachers were tasked with screening a child’s literacy by asking them to read words. From there, the new method of phonics was employed to help those that proved barely literate. Between 2012 and 2014, the proportion of pupils meeting the expected standard increased from 58 per cent to 74 per cent (we go in to more detail later the educational outcomes born from these reforms).

As part of an effort to enforce rigour and higher standards in the classroom, SATs held in 2016 were made harder with the introduction of tougher Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar (SPAG) tests. The English Baccalaureate (EBacc) was introduced to focus students on studying core subjects of English, Maths, Science, Geography, History and a language, and not being syphoned off in to ‘low value subjects’. School performance is measured according to student performance on the EBacc, and the Government have set the ambition that 90 per cent of students will study the EBacc by 2025.

Alongside the new EBacc there was a new measurement of student and school performance introduced in 2016, Attainment 8 and Progress 8. Progress 8 was the first attempt to help measure performance of students over time – who had helped their students outperform national or local performance.

The most significant piece of funding reform was the Pupil Premium. Introduced in 2011, a core part of the Coalition agreement and originally a Lib Dem idea, it is a sum of money that a school will receive based on the number of disadvantaged pupils they currently have on their roll. If a student qualifies for free school meals, is currently under Local Authority care, or receives a child pension from the Ministry of Defence, a school can claim between £300 and £2300 for their teaching. Finally, universal free school meals were introduced in 2014 for students in reception years 1 and 2.

Education outcomes

The outcomes achieved by these reforms speak volumes. In August 2010 4.8 million, or two-thirds of children, were learning in a Good or Outstanding school (as defined by Ofsted). In 2018, that figure had grown to 6.7 million, or 86 per cent of the school population.

In early years, the percentage of children achieving a good level of development has increased from 51.7 per cent in 2013 to 71.5 per cent in 2018. The introduction of early years and a greater emphasis on phonics in the classroom has helped boost 9-10-year-old reading ability against international competitors, which has shown up in the PIRLS study. As the Guardian said in 2017, “English children who took part in the 2016 tests, the results of which were released on Tuesday, were ranked a creditable joint eighth out of 50 participating countries. They scored the same as their peers in Norway and Taiwan and climbed up from 10th position in the last round of tests five years earlier. They registered their best average reading score of 559 and are gradually climbing back up the rankings after a dramatic fall from third position in 2001 to 15th position in 2006”.

The extent to which improved educational outcomes for young students is down to availability of Universal Free School Meals is of course difficult to say. However, a survey of parents from the Education Policy Institute found that parents “cited significant financial benefits as a result of UIFSM and have appreciated the time that has been saved from not having to make packed lunches, [with] some, though generally less than half, of the school and parent/carer respondents to surveys [perceiving] positive impacts in the short term on educational, social and health outcomes… and Many school leaders [believing] UIFSM has improved the profile of healthy eating across their school”.

At the Key Stage 2 level SATs test, despite a ‘hardening of the test’, since 2016 there has been an increase in the percentage of children reaching the expected standard in reading, maths and the GPS test.

As then Education Secretary Michael Gove said in 2010, “A child eligible to free school meals is half as likely to achieve five or more GSCEs at grade A*-C, including English and maths, than a child from a wealthier background”. Now that attainment gap, although still big, has reduced significantly. According to the Education Endowment Foundation, that attainment gap has halved to just 25 per cent. As the school moves to being in less deprived neighbourhoods, the attainment gap closes (although this has more to do with less disadvantaged kids performing poorly). The attainment gap index, produced by the Department for Education, has fallen from above 4.0 to nearly 3.5 since 2011.

The number of level 3 qualifications has also increased, as the CSJ highlighted in a recent report “Department for Education data only goes back as far as 2004, in which time there has been a 43.7 per cent increase in the percentage of students reaching the Level 3 attainment level. In 2017, 373,855 students, 60.6 per cent of the cohort, had achieved a level 3”.

Finally, application rates for higher education institutions have risen significantly in England, Scotland and Wales (while remaining flat in Northern Ireland). Application rates have risen for disadvantaged students (even though they are still less likely to go to university). In England application rates for disadvantaged students has risen from 15 per cent in 2009 to 23 per cent in 2018.

The truth about school spending

School spending has become an ever more hotly contested political issue, in which little room is given for nuance and anything resembling a cut is decried as near criminal. Labour have put in a huge amount of effort in claiming the Conservatives in Government have cut education spending. Like all forms of spending, you can cut the data in different ways to suit your own purposes.

- Total education spending has fallen by 13 per cent in real terms since 2010 but risen by 52 per cent over a 20-year period. As a share of national income, total education spending in 2018 was 4.3 per cent, lower than in 2010 (5.8 per cent) but higher than 20-years previously (4.0 per cent). As the IFS say, total spending reductions were “mainly driven by a 55 per cent cut to local authority spending on services and cuts of over 20 per cent to school sixth-form funding. Funding per pupil provided to individual primary and secondary schools has been better protected and remains over 60 per cent higher than in 2000–01, though it is about 4 per cent below its peak in 2015.

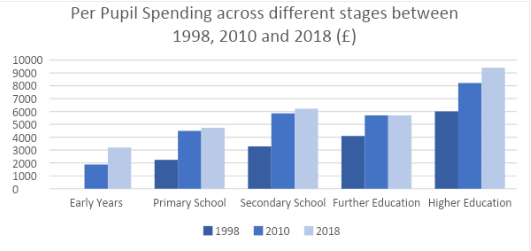

- Spending by education stage:

- Early years, a relatively new spending area, has grown significantly under the Conservatives in Government. Between 2010 and 2018 there was a total increase in spending of 13 per cent from £5.2 billion to £5.7 billion. In per pupil terms, spending has increased by 70 per cent (the largest increase of any area) from £1,877 to £3,194.

- Primary school: Between 2010 and 2018, primary school spending has increased by 5 per cent, from £4,487 to £4,737. However, since 1998, a 20-year time period, per pupil primary spending has more than doubled from £2,242.

- Secondary school: Between 2010 and 2018 per pupil spending at secondary level has increased by 6 per cent from £5,846 to £6,210. Since 1998 the increase has been 89 per cent.

- Further Education (part of the wider adult education budget) has seen some of the most significant cuts in recent years. In 2018 total spending was £3.5 billion, 15 per cent lower than in 2010, but 40 per cent higher than in 2002 (the oldest data available from the IFS). In per pupil terms, Further Education spending (calculated per Full Time Equivalent student) is flat since 2010, and 39 per cent higher over a 20-year period.

- Higher education spending is calculated by the IFS as teaching resources provided per student. Between 2010 and 2018, spending per pupil has increased by 17 per cent from £8,211 to £9,395. Over a 20-year time period, spending has increased by 56 per cent from £6,004.

The Labour alternative

Despite all the success of the last eight years and the financial constraints under which it was introduced, Labour has vowed to tear up the Government’s reforms. What is it offering instead?

Labour’s headline policy is a National Education Service. It encapsulates a number of ideas, of which the most significant is pulling funding for free schools and investing in Secondary Moderns. This despite Free School students outperforming the national average and Secondary Moderns not existing in British education landscape since the 70s. Outside of this structural change the party has made huge commitments to increase funding for both early years and further education, including the introduction of free higher education.

Labour also plan to scrap SATs. By doing so, the party risk making the most vulnerable worse off by getting rid of the best accountability mechanism schools have. As one teacher said recently in the Guardian, “we would probably fall back on teachers’ own assessments to measure children’s progress and attainment. This would be a reckless leap of faith, and would increase teacher workload, while leaving our most vulnerable children at the mercy of notoriously unreliable judgments”.

Getting rid of assessments has been tried before, with Science. Since then the percentage of students reaching the expected level has fallen from 88 per cent to 23 per cent. Wales scrapped tests for 7- and 11-year olds and saw performance in PISA surveys decline shortly afterwards. In Scotland SATs for 14-year olds were scrapped and not long after standards fell significantly, particularly for the most disadvantaged.

The Opposition also proposes increasing the power of Local Education Authorities. Remarkably, Labour want to return to a situation where councillors run schools. On their website they say, “Labour will ensure that all schools are democratically accountable, including appropriate controls to see that they serve the public interest and their local communities”. Many teachers believe increasing the power of Headteachers to make decisions has resulted in better schools and better outcomes for students. Giving councillors more control takes education out of the hands of educators.

What more can be done?

Why does all this matter? Everyone understands the importance of a good education. For some it can be the difference between achieving the good life or falling onto an altogether different path. It is worth remembering that the recent spike in knife crime has been linked (in part) to the exclusion of challenging children in schools and parking them in Pupil Referral Units.

Recent work at the CSJ found that “only 1 per cent of children who take their GCSEs in alternative settings achieve five good passes. And less than 5 per cent pass English and Maths, the two basic qualifications that unlock the door to future training, education and employment” resulting in non-mainstream schools becoming breeding grounds for gangs and drug dealers.

Considering all of this, Labour want to reverse some of the policies that have helped increase the number of good and outstanding schools in Britain, boost pupil attainment, improve literacy and numeracy rates, increase higher education application rates and reduce the disadvantaged attainment gap. Of course, more improvements can be made.

The appalling performance of students at PRUs needs to be addressed, there needs to be better technical education provision, the challenges that disadvantaged children face in the classroom is still too low, and white working-class boys are still lagging almost every other group.

However there is little doubt though that reforms to our education system have been among the most successful efforts to improve life chances for many of the most vulnerable in Britain. For this Conservatives should shout loud and be proud.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.