There is no doubt we live in exceptional political times. What happens in Parliament this week will be of huge significance to Britain’s future. However, amidst Brexit I fear we have lost sight of policy and politics on what really matters, namely improving the life chances and opportunities of the most disadvantaged people in Britain.

The sooner this changes, the better. I think it is high time the Conservative Party got back to talking about tackling poverty and social deprivation across our country. It would be the right thing to do in terms of good governance. It is also a conversation Conservatives need not be shy about. Since 2010, their record on tackling poverty and social deprivation is strong.

The left has always had a strangle hold on compassion. Today, the Labour Party is more pious than ever in its assertion that only they speak for the poor. This has fed through to voters. Speaking to people about politics, it is a given that the Conservatives are trustworthy on the national finances, defence and managing the economy. But it is a tougher sell to suggest the Tories, and not Labour, are the party of compassion, life change and tackling poverty. Our record on jobs, education, welfare, economic mobility and growth has been lost.

This article is the first in a series of four in which I hope to debunk the myth that being right wing is mutually exclusive with compassion. I want to prove that contrary to the left-wing narrative, the right’s record on tackling poverty is something to be proud of.

In this article I will talk about the Conservative record on welfare and employment. The next instalment will focus on home ownership and the family. After that I will talk about education and how reforms to our schools have benefited the most disadvantaged in society. In the fourth article I will talk about free markets, capitalism and technology and how being pro-trade is fundamental for alleviating economic hardship. I hope these articles can reignite the discussion on social justice in post-Brexit Britain.

Welfare vs work

A compassionate society needs a strong social safety net to protect people against shocks to their income and in times of emergency. However, the division between left and right is most obvious on what role welfare plays in reducing poverty.

The left is adamant that incremental increases in welfare spending can lead to incremental reductions in poverty. The Labour Party have led the attack on ‘Tory austerity’ by linking it to ‘record levels of poverty’.

Welfarism isn’t just confined to political parties. The Child Poverty Action Group argue for just two policies to reduce child poverty in Britain; more generous working age welfare benefits and increases to child benefit allowance. Russel Gunson for IPPR argues for the same as a means of reducing poverty in Scotland. Blairite think tank Progress have called for more generous housing entitlements and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have called for an end to the benefit freeze as a means of reducing poverty in Britain. The Guardian has always laid blame for the perceived increase in poverty squarely at the foot of ‘Tory cuts’.

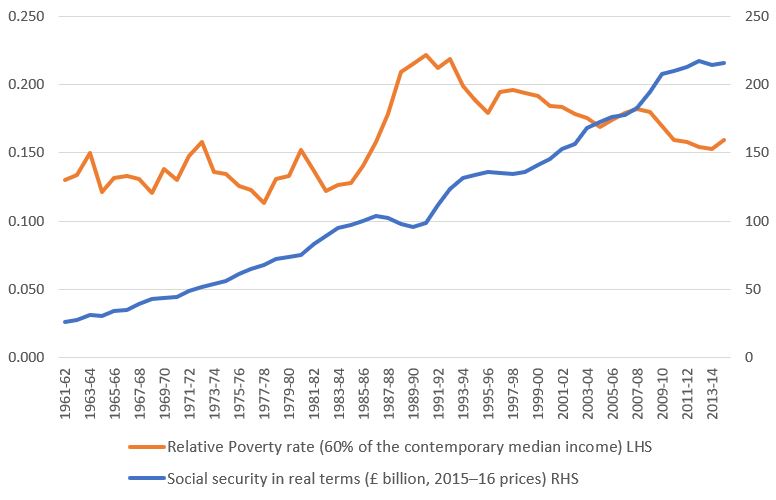

However, what is the evidence to back this claim that welfare is the single most important tool in reducing poverty? Firstly, figures from the IFS show that while the amount of social security spending has risen exponentially, the relative poverty rate has pretty much stayed between 15 per cent and 20 per cent (with a general downward trend since the early 90s).

It is also worth remembering what the welfare state looked like when the Conservative’s came in to Government. The huge increase in welfare entitlements (including tax credits) and their complexity had created a welfare trap. By 2010, 12 million people were claiming some form of benefit. Despite almost a decade of uninterrupted economic and job growth, 2.6 million had spent the majority of that time claiming out of work benefits.

A higher proportion of British children were growing up in a workless household than in almost any other EU country. As the Government said about welfare dependency in 2010, it is “strongly linked with poverty and reduced well-being, poorer physical and mental health and an increased likelihood of becoming involved in the Criminal Justice System”. Between 1997 and 2009 annual social security spending had increased by 53% from £135 billion, to £207.9 billion while relative poverty rate (see above) had fallen from 19.6 per cent to 16.9 per cent – just 2.7 percentage points.

While the left is unabashedly ‘welfarist’ in their approach, the Conservatives have generally been more focussed on improving employment prospects for all people. Of course, not everyone can work. The young, the old and those who face mental and physical health issues cannot be expected to work and should expect support.

However, for working-age people, work confers benefits that the welfare system simply cannot. The Royal College of Psychiatrists are unequivocal: work is good for both someone’s mental and physical health, as well as their sense of purpose and dignity. In a recent interview with ex-offenders I was told by many of how losing their job had been one of the biggest issues they faced in jail and gaining employment had been the most catalytic and positive moment after being released.

The data backs this up – being unemployed increases the probability of being poor by a factor of four. The Department for Work and Pensions Households Below Average Income survey data shows that the poverty rate for adults in workless households was 38 per cent compared to 10 per cent for adults in working families. A child from a workless household is twice as likely to fail at every stage of their education compared to a child in a working household.

What about in-work poverty and bad jobs?

The argument against the importance of work currently revolves around the high rate of in-work poverty and the emergence of atypical employment (gig employment) that are considered bad jobs. Many claim that in-work poverty is the greatest challenge to solving poverty in Britain. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, for example, cite the fact that over “half of people in poverty in the UK live in a family where at least one person is in paid work”.

In-work poverty is a problem, but its growth has been almost entirely down to record employment growth. The Department for Work and Pensions explained the mathematical phenomenon in March 2018: “Overall, 32.3 million working-age adults were in working families, and 6.5 million working-age adults were in workless families. 10 per cent of 32.3 million is greater than 38 per cent of 6.5 million, meaning overall 57 per cent of all working-age adults in low income were in working families”. In work poverty is still poverty yes, but it doesn’t invalidate the theory that work is the best route out of poverty.

The notion too that someone is always better off on benefits than working on the fringe of the labour market in the gig economy is also mistaken. A University of Manchester study found that those with a poor-quality job fared worse in mental health terms compared to those who stayed in employment. I don’t think anyone can doubt that the mental and physical stress related to being low paid and over worked. James Bloodworth’s account of working in an Amazon warehouse in his book Hired was at times shocking. However, Bloodworth and the academics in Manchester say nothing about the long-term effects of keeping a job (even if it is a bad one).

Research on laid-off factory workers in America found that those who stayed in work (taking a demotion if necessary) as opposed to becoming unemployed (and taking up retraining opportunities) were better off in the long term. On average the cohort who prioritised work (over welfare) had higher employment rates and higher wages after four years.

The Scandinavian example

Of course, lots of people on the left also argue that the Scandinavian model of social security – incorporating higher cash transfers – has yielded exceptional results. However, despite having a higher employment rate, Sweden is no more generous than the UK, spending 28.7 per cent and 28.6 per cent of GDP respectively on social protection in 2015 (see Eurostat). In fact, the UK spends more than most other major European countries including Germany, Norway, Iceland and the Netherlands. Only Finland and Denmark stand out as an example of high social security spending in Scandinavia, both spending more almost a third of GDP. Incidentally, both Finland and Denmark incidentally have lower employment rates than the UK.

Conclusion: Winning the economic argument

The big (non-Brexit related) debate in Westminster at the moment is very much one between those who believe work is the best route out of poverty and those who do not. The evidence presented here is clear: economic empowerment and social mobility is best achieved by ensuring everyone has access to a safe job and a decent income.

The Conservative Party in government has helped power the labour market to record levels with the highest employment rate in recorded history.

Contrary to what you would might read in the Guardian, jobs created have been mostly full time and higher skilled. A CSJ publication released earlier this year found that:

Between 2006 and 2017, there was a significant increase in the number of high skilled occupations (Managers, Directors, Professionals and Associate Professional positions) in the UK economy in the order of 1.9 million new roles. Over the same period there was an increase of just 509,744 jobs that are considered mid and low-skilled… Over this period, low-skilled occupations declined as a share of the UK labour market. In 2017 they made up 36 per cent (a decrease of 2 percentage points since 2006) of jobs, compared to higher skilled occupations which made up 44 per cent (an increase of 4 percentage points) of jobs.

As the Resolution Foundation pointed out in January, the benefits from this employment boom have largely been accrued to the most disadvantaged in society:

We find that record employment has been progressive… Between 2007-08 and 2016-17, people living in households in the bottom half of the income distribution accounted for 62 per cent of the employment increase…The jobs-boom has brought some of the most disadvantaged groups into employment. Ethnic minorities and people with relatively low qualifications have been among the main beneficiaries, as have people with disabilities.

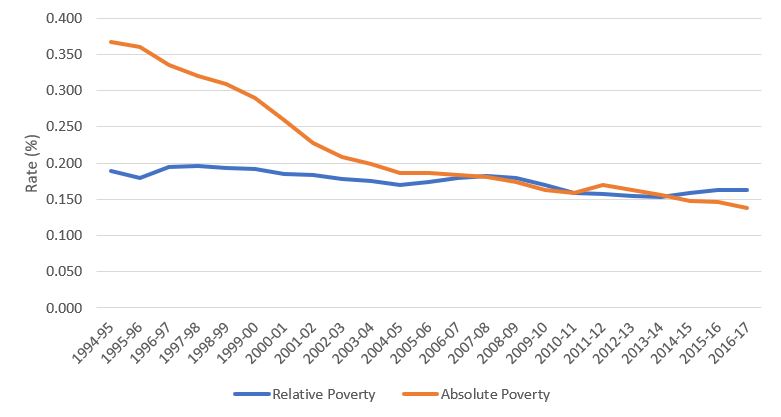

This success is starting to become more visible in the poverty figures. Poverty measures are controversial. People disagree with the use of relative poverty rates because a fall in the median wage can counterintuitively result in a decline in poverty. Absolute poverty is a more practical measure because it reflects long term material progression. The IFS figures show the number of people in absolute poverty (understood to be number of people with an income falling below the median wage in 2011) has fallen from 10.5 million in 2011/12 to 8.8 million today. As we mentioned earlier, even if you do insist on using the relative poverty measure, there has been a steady decline in the rate since the mid-90s.

So, in summary, the derision that many of the right receive on the issue of tackling poverty and social deprivation is not supported by the evidence. Since 2010, employment rates have gone up and poverty rates have fallen.

Work is consistently proven to be the best route out of poverty and while social security plays an important role in providing support for those in emergencies, it does not offer the answers to solving poverty in the long term.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.