When pressed on the details of her plans for leaving the EU in December 2016, Theresa May didn’t offer anything of substance. Her reply was simply that she wanted a “red, white and blue Brexit”. As we and colleagues show in newly published research, it seems the British public agrees with her – just as long as the red, white and blue she’s referring to are that of the Norwegian flag.

One of several key findings from our research was that, given how much value the public place on the UK making its own trade deals and having access to the single market, they would prefer to have a relationship with the EU similar to that of Norway. This allows for free trade with other countries, while remaining within the single market and accepting freedom of movement and some loss of sovereignty to EU institutions, such as the European Court of Justice.

To reach this conclusion The Policy Institute at King’s College London, along with RAND Europe and the University of Cambridge, used an economic approach known as “stated preference discrete choice experiments” to measure how the British public value different components of a Brexit deal. This is more rigorous than traditional polling, and involved interviews with 917 people, drawn from those who participated in the British Social Attitudes survey.

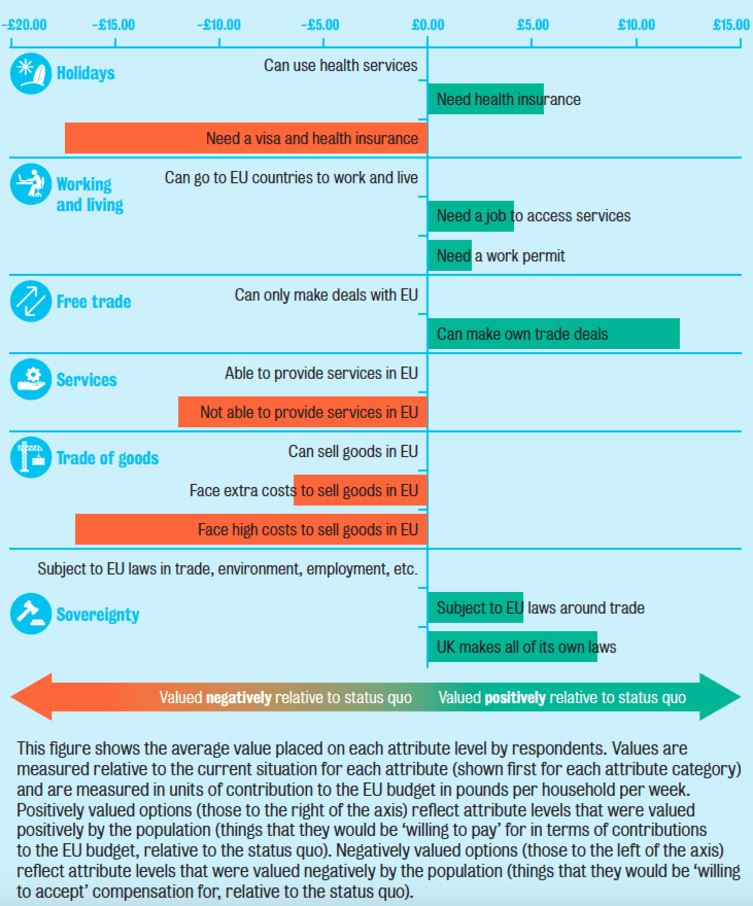

We asked people to make choices, and trade-offs, between hypothetical options for a Brexit deal, to elicit their preferences. This contrasts with opinion polls, which ask people to report their preferences directly, and by doing so can be subject to various distortions, such as the pressure to give socially acceptable answers. Our approach enabled us to also assess the relative strength of people’s preferences for each attribute of a Brexit deal, meaning we could quantify how acceptable a range of different scenarios are likely to be to the population as a whole.

Single Market trumps immigration controls

What we found contradicts some of the received wisdom about the Brexit vote. The outcome of the referendum has been interpreted by many as a decisive rejection of the UK’s approach to immigration. But our research showed that, for the public, restricting freedom of movement is not as important as the ability to make trade deals and retain single market access. In fact, it was not restrictions on freedom of movement per se that people cared about the most – their desire for such constraints seemed to stem from concerns about pressure on public services.

The research showed a preference for the requirement that EU nationals living or working in the UK must have a job in order to access public services – and correspondingly, for the same conditions to apply to UK citizens in EU member states. And on movement for holidays, while the public prefer everyone to have health insurance to cover emergencies, they were keen for there to be as little red tape as possible. Their desire for people to be able to travel visa-free – whether Britons visiting Lisbon, or Bulgarians visiting London – was the most strongly valued statement across all of the attributes included in the study.

Little appetite for “no deal” Brexit

The research also raised questions about another of the prime minister’s memorable declarations on Brexit – that “no deal is better than a bad deal”. This frequently heard mantra has come under increased scrutiny in recent days. In early July, a survey of British businesses found that 98% of those polled think “no deal” on Brexit is unacceptable.

A few days later the foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, seemed to suggest that leaving the EU without a deal was not in fact a realistic option for the government. “There is no plan for no deal because we are going to get a great deal,” he said.

Our study found that the British public also have significant reservations about a “no deal” scenario. Put simply, it appears that they would disagree with the prime minister’s claim: they want a proper Brexit deal, and do not wish the UK to fall out of the EU on World Trade Organisation terms.

![]() All of which suggests that the public are more conducive to compromise than some may have assumed. They recognise it is not possible to have everything they want – and are willing to make concessions. As the second round of Brexit negotiations begin on July 17, it remains to be seen whether the government will enter the discussions with a similar mindset. It may be eager to give the public what they want – but our research suggests that this isn’t a Brexit at any price.

All of which suggests that the public are more conducive to compromise than some may have assumed. They recognise it is not possible to have everything they want – and are willing to make concessions. As the second round of Brexit negotiations begin on July 17, it remains to be seen whether the government will enter the discussions with a similar mindset. It may be eager to give the public what they want – but our research suggests that this isn’t a Brexit at any price.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.