Those on the left always used to have a simple diagnosis for the housing crisis. Housing was in short supply because, from Thatcher onwards, government stopped building council houses. The state became to reliant on the private sector for delivery. There are criticisms to be made of this argument, but its main thrust – that the housing crisis results from a housing shortage caused by underbuilding – is at least in keeping with economic consensus.

However, a different strand of thinking has gained prominence lately. It is epitomised by Labour’s Land for the many report, published this week, which blames Britain’s housing shortage not on a lack of houses but on the ‘financialisation’ of land. Housing costs, they claim, have soared over time mainly because of an expansion of mortgage lending and speculative investment by buy-to-let landlords and anonymous foreigners.

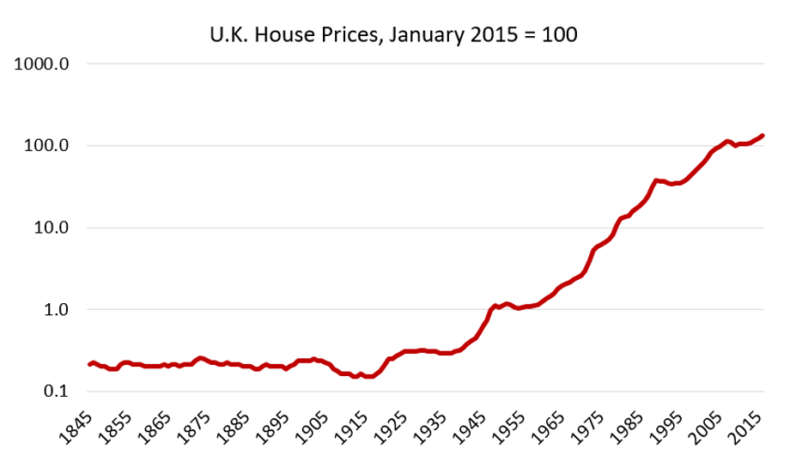

The main argument is that since the 1980s, financial deregulation under Thatcher has led to large-scale speculation of land which has made housing unaffordable. The primary problem with this claim is that it is at odds with the history of house prices in Britain, which have been on the rise since the 1940s.

The beginning of this increase does not coincide with the introduction of mortgages, buy to let or wealthy foreigners. However, it does coincide with the introduction of the modern English planning system in 1947.

The act created a distinction between land in general and land with planning permission which could be built on. Before this act theoretically any piece of land could be built on, afterwards only land which had been given permission by the government could be developed. This led to a rapid restriction on the amount of land available. This event, according to the late planner Sir Peter Hall, caused ‘the inflation of land and property values on a scale never before witnessed’.

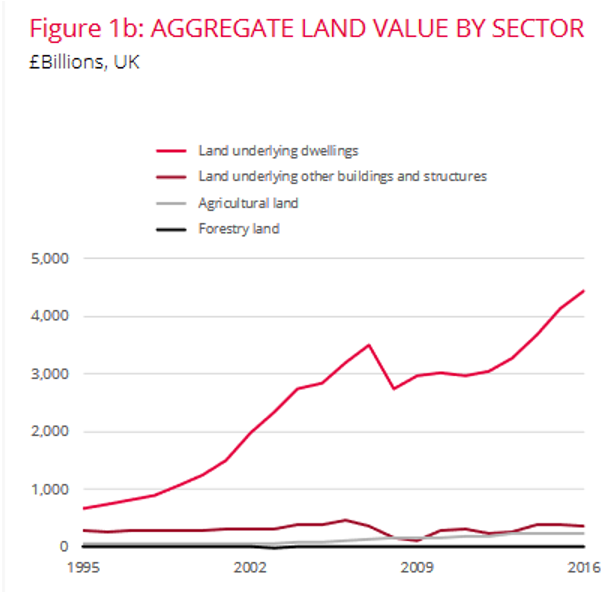

Underlining this point, it is only the land with permission to be built on which has grown rapidly in price. This is the distinction that the labour report fails to make, although it is evident from the data.

Who owns the majority of this lucrative land? Which capitalists have gained the fruits of this ruthless speculation? The answer is simply ordinary homeowners, who own 77 per cent of it. Yet their report is effectively silent on how to decrease the value of this land or use it more efficiently. All it suggests is some minor reforms to council tax, ruling out more substantial reforms on the grounds they will be too unpopular.

So here we find the crux of the problem: any reform that affects the bulk of the land value in this country is politically impossible because homeowners are a majority of the British population. This is why their proposed reforms only ever tinker around the edges and will never be able to implement the financial reforms required to stop homeownership from being financially lucrative.

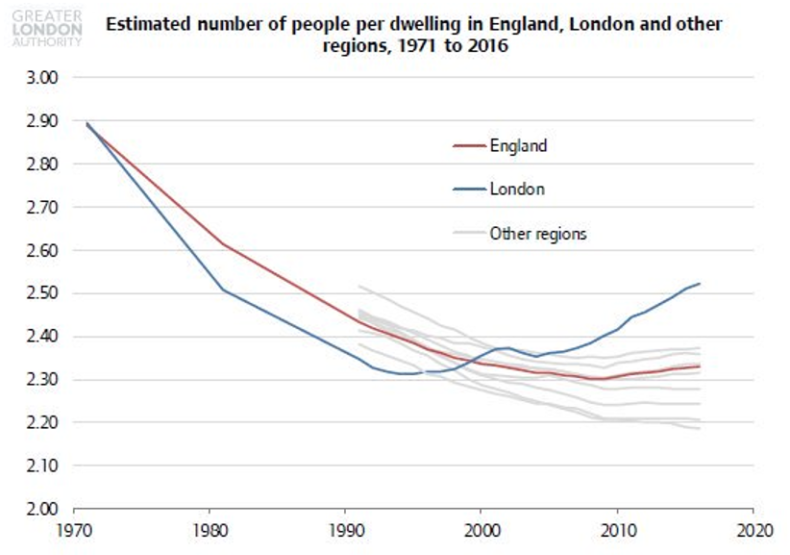

The report also completely sidesteps the issue of land use and housing supply, embracing NIMBY arguments that there is no housing shortage because housing supply has outstripped household formation. This ignores the research that shows that high housing costs are suppressing household formation by forcing young people into co-living or living with their parents. That trend is also evident in the increase in average household sizes experienced recently, particularly in high demand areas.

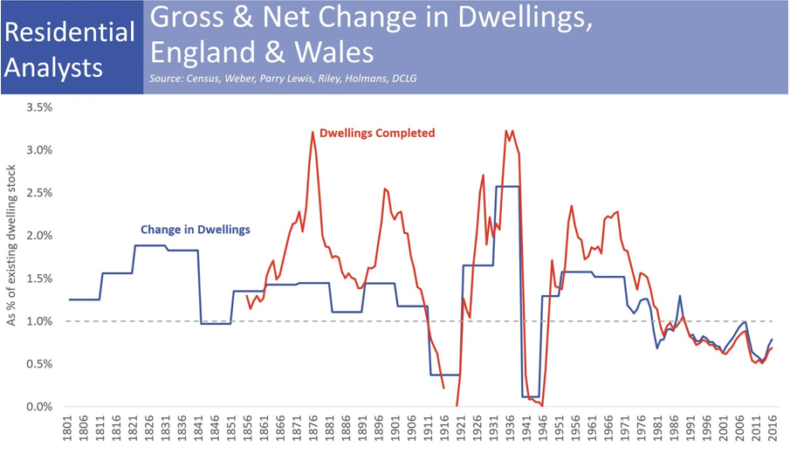

Historical data once again shows that the current system of planning has led to reduced levels of growth in housing supply. Since 1947 we have never been able to grow the housing stock at the rate achieved in the 1930s, or even the 1830s for that matter. This, of course, coincides with the growth in house prices mentioned above.

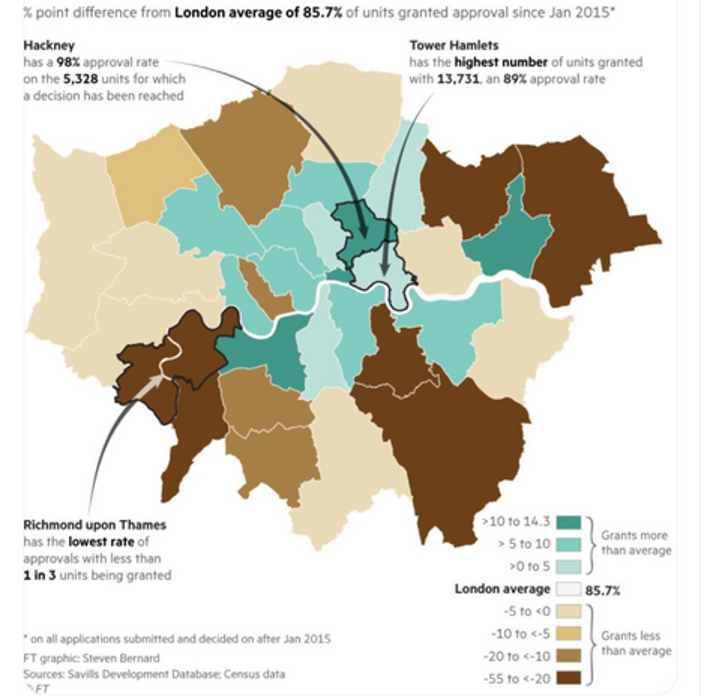

Likewise, areas in which supply is restricted the most are wealthy suburban areas with higher levels of homeownership. These areas approve far less housing.

You would have thought that left-wingers would want to open these areas up to higher density land use to make these areas more affordable. Equally an environmentalist like the report’s main author, Guardian columnist George Monbiot, should want to consider how to increase density near public transport and upgrade existing car-dependent sprawl into denser, more walkable neighbourhoods. Yet this is not mentioned.

They fail to realise that homeowners, like developers, are also holders of capital seeking to maximise the value of local commons and the value of their house. Therefore, the planning reforms that they suggest, which will increase local control over issues such as how many houses to build, will allow for more rent-seeking behaviour and the continued restriction of affordable housing by wealthy neighbourhoods. This will exacerbate Britain’s housing shortage and push up land and house prices even further as a result.

Land for the many attempts to launch an attack upon landowning capitalists without actually understanding who they mainly are, ordinary homeowners themselves. Instead of suggesting feasible ways to make housing more affordable in a society with this homeowner majority, it simply descends into the populist tropes of NIMBYism and the dog whistle of blaming non-existent wealthy foreigners. In doing so, it offers no solutions to Britain’s housing mess.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.