It’s a pattern as predictable as the water cycle itself. Britain has a drought. The newspapers discover that billions of gallons are being wasted through leaks. There is unanimous agreement that the water companies must be punished. The Guardian calls once more for nationalisation.

It’s not just the left that get agitated. In the last few days, both Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss have weighed in to castigate the water companies for permitting too many leaks.

Ed Davey, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, has gone even further. He told The Independent that consumption targets ‘feel utterly pointless whilst Thames Water waste a quarter of all their water from leaking pipes’. He added: ‘It is time someone stood up to these companies. That should start with a sewage tax to clean up rivers they pollute and a ban on CEO bonuses until pipes are fixed.’ But this entire narrative rests on a galactic misunderstanding about how the water industry in the UK operates.

The way everyone thinks of the water industry is as, well, an industry. The private companies running it get up to whatever mischief they like, while the hapless regulator tries in vain to stop them.

But the reality is that the water companies are essentially contractors. They are running the water network on behalf of the state, in a fashion agreed with the state, to targets laid down by the state.

Let’s take the issue of leaks. The reason that just over 20% of Britain’s water is lost to leaks (although drought is pushing that number up) is because that is the level set by the regulator.

Way before privatisation, economists came up with a concept called the ELL – “economic level of leakage”. (The water regulator Ofwat later added the word ‘sustainable’, to create the SELL.) The basic idea is that some leaks are too expensive to repair, not least given the fact that much of our water infrastructure is inherited from the Victorians. So it can be more cost-effective just to pump more water to compensate.

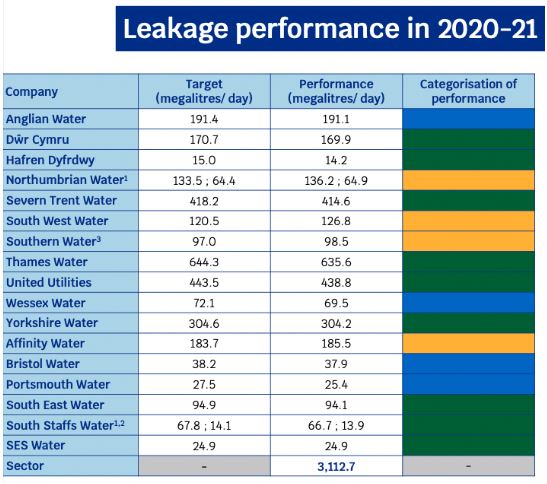

This chart, taken from Ofwat’s annual Service Delivery Report, shows how the companies have been doing in terms of leaks. As you can see, all of them are at or near the level of leakage agreed with the regulator.

.

.

So if we want to bring down leaks, there is a very simple solution. We don’t shout at the companies. We shout at the regulator.

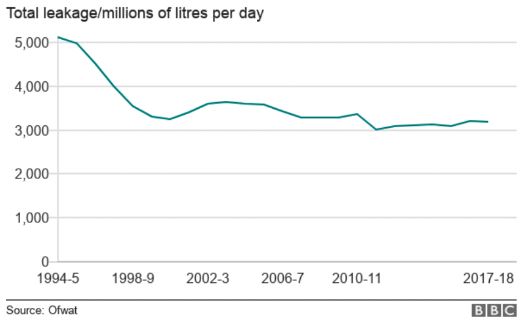

In fact, this is precisely what happened in the late 1990s. The Government decided (particularly in the wake of another nasty drought in 1995) that too much water was being lost to leaks. So the ELL was adjusted. Leakage miraculously fell.

.

.

And by the way, this is obviously not a purely British problem. Below are the latest pan-European figures on leakage, from the European Federation of National Associations of Water Services, which goes by the rather brilliant name of “EurEau”. It turns out the Germans, Danes and Dutch are very good at preventing leaks. The rest of the continent, not so much.

.

.

Now, you might say that it is not ideal in the modern age to set levels of acceptable leakage so high, given climate change, water shortages and whatnot. And do you know what? Ofwat would agree. That’s why, in 2019, it ditched the SELL and told the water companies that they had to start reducing water leakage – without raising bills. And, as if by magic, they have. Since 2017/8, the final year in the chart above, water leakage has fallen by 11%. Between 2020 and 2025, Ofwat expects leakage to fall by 17% – the equivalent of the entire water consumption of Manchester, Leicester, Leeds and Cardiff. And the ultimate target is to halve leakage by 2050.

In other words, leaks are already falling. And if we want them to fall faster, we should adjust the targets – not blame the companies for doing exactly what they’ve agreed with government to do.

But what about pollution? Aren’t those companies all pouring far too much sewage into our beloved rivers?

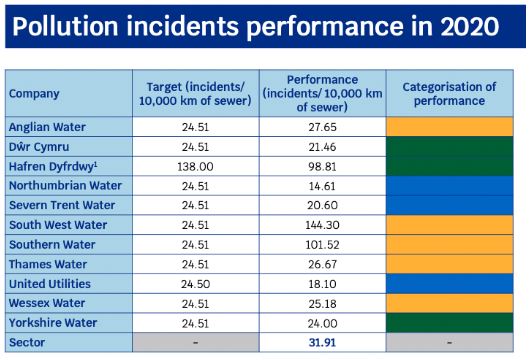

Well again, unsurprisingly, this is an area which is heavily monitored by government. Here’s the chart, from the same report..

.

The results here are not as good as on leaks. But they are distorted by the monumentally bad performance of Southern and South West Water, both of which were fined millions by the regulator as a result.

In other words, Ed Davey’s ‘sewage tax’ already exists. He may think it is inadequate. But again, the way to fix that is to tell the regulator to toughen up its punishments.

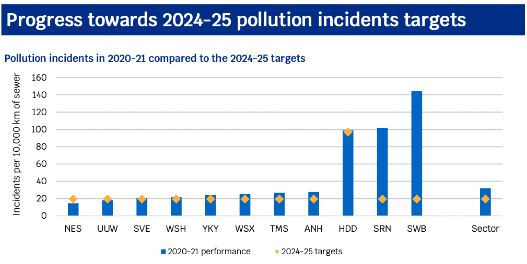

In fact, again, that’s exactly what is happening. Ofwat and Natural England have told the water companies to cut pollution. And pollution is (with those two glaring exceptions) being cut. Most of the other companies are already at or near their pollution reduction targets for 2024/5.

.

.

Then there is the issue of domestic water use. This was the focus of the Independent piece in which Davey was quoted, under the headline: ‘Water firms fail on targets to cut household leaks and domestic use as drought looms.’

The story did not actually provide any statistics on household leaks – although, as we have seen, leaks from the network as a whole are already falling. But it is certainly true that every water company missed its targets for domestic water consumption.

However, as Ofwat points out, that has rather a lot to do with the fact that a lot more people have been spending a lot more time in their homes, thanks to the pandemic. I imagine that any targets there may be for cutting water use in Britain’s offices have been going swimmingly.

What about the rest of the charge sheet against the privatised water sector? That Guardian editorial provides a useful summary. Companies have racked up debt. They have failed to adequately invest in infrastructure. Prices have risen. Private-sector efficiency did not provide better service.

On the point about debt, the companies are certainly guilty as charged. Though, of course, one reason the companies have taken on so much debt is that they were so limited by the regulator in terms of the profit they can make: they have effectively been borrowing against their own future, heavily regulated, revenue streams.

As for the point about private-sector efficiency, the water industry estimates (using figures from Ofwat) that bills are £120 lower than they would have been thanks to the current regime. It points out that customers are five times less likely to suffer supply interruption and 100 times less likely to encounter low pressure than 30 years ago, and that bills have not risen in real terms for the last two decades.

As I pointed out in a CapX piece back in 2018, analysis by Frontier Economics showed that in 2017, productivity in the water sector was up by 64% since privatisation, meaning that annual costs were some 27% lower than they would otherwise have been. This contrasted with productivity gains of approximately 30% in comparable sectors, and pretty much zero in the public sector as a whole. Seems pretty efficient to me.

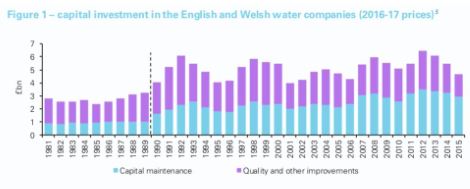

But the key point here is the one about investment. Yes, prices initially rose after privatisation. But they did so because there was an extraordinary backlog of investment to make up, which simply hadn’t been happening during the nationalised era. Just take a look at this chart – the dotted line, fairly obviously, represents the transition to privatisation.

,

.

Which is where we come to the single greatest justification for privatisation: competition for capital.

In response to the demands of climate change, an increasing population and so on, we are planning to spend very large amounts to upgrade our water infrastructure. That same Ofwat review that tightened the rules on water leakage committed to £51bn in capital spending between 2020 and 2025.

If the water network is in public ownership, then that borrowing requirement is in competition with every other piece of capital spending on the government’s wish list. And during the nationalised era it always, always lost out to schools and hospitals – and was always going to.

We don’t even need to look at the past to make the comparison. Northern Ireland’s water network is still publicly owned. And it’s in a terrible state, because it has never been given the funding it needs. Scotland is doing better. But that, as this report from industry expert John Earwaker says, is because it decided after years of under-performance to benchmark its publicly owned supplier to the standards set by England and Wales – effectively copying their homework.

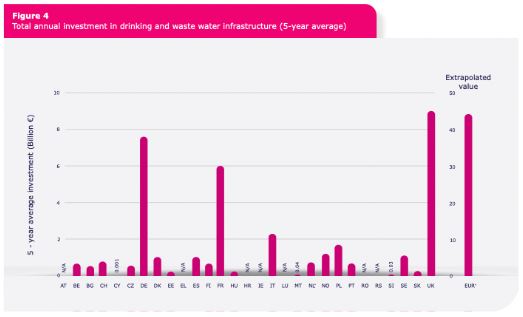

Again, it’s helpful here to compare our situation with the rest of Europe. Looking at EurEau’s figures, it turns out that one country is currently investing much more in repairing and upgrading its water network than anywhere else. That’s right: us. (Perhaps appropriately, we’re the one furthest to the right on this chart.)

.

.

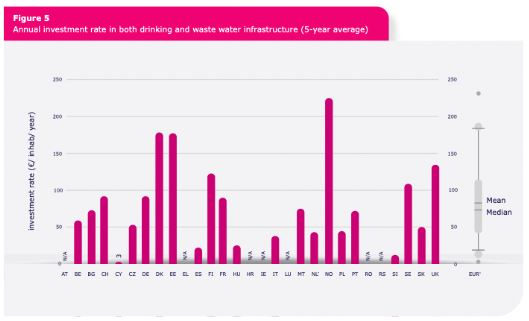

Admittedly, the picture changes when you adjust for population. But we are very clearly investing in our water infrastructure on a very serious scale.

.

.

I’m not trying to claim that privatisation is a panacea. There are plenty of things wrong with the current system: witness the way that the companies have piled on debt, as mentioned above. (If you want a fuller list of their failings, the best place to start is this speech by Michael Gove, during his time as Environment Secretary.)

But it’s a bit grating to hear knee-jerk calls for nationalisation from people who apparently have absolutely no understanding of how the water industry is structured, or the incentives it operates under, or the changes and improvements that have happened since privatisation.

And it’s also depressing to hear senior politicians threatening the water companies for their performance over leaks when that performance is a) entirely driven by the regulator’s requirements, b) improving dramatically and c) part of the largest water infrastructure investment programme in Europe.

‘It is time someone stood up to these companies,’ says Ed Davey. How about we try telling the truth about them instead?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.