The UK’s decision to leave the EU has created huge uncertainty: over what sort of trade agreement we might have with them in the future and the resulting tariffs that UK firms can expect to pay in order to export from the UK to the EU.

Leaving the Customs Union will also open up firms in the UK to further potential trade restrictions introduced by the EU under the World Trade Organization’s laws on anti-dumping orders, countervailing duties and safeguards.

This uncertainty has been compounded by the Trump administration’s action over UK access to the valuable US markets. As a result, firms in the UK now have to decide whether to enter new foreign markets, continue in established markets, or invest in their productive capacity without knowing much about their future access to these markets.

Such uncertainty can have permanent effects on an economy by reducing the incentive for firms to invest.

In the case of trade policy, a recent study quantified the impact of an increase in trade policy uncertainty on Chinese exporters and found that threats of tariff increases – that never actually materialised -reduced Chinese exports by at least $28 billion over 2001-2009. Even when the current uncertainty about UK access to markets around the world is resolved, a concern is that decisions being made or delayed today will be likely to have permanent negative impacts on the UK economy.

To try to clarify matters, we conducted a detailed analysis of the exposure of UK exports to EU tariffs under a “no deal” scenario. We identified, by product classification, the value of UK exports to the EU facing trade policy uncertainty.

Our view is that there are four major sources of trade policy uncertainty facing firms in the UK:

(1) uncertainty over the baseline tariffs and quotas the EU will impose on imports from the UK in the future;

(2) uncertainty over the special trade barriers that the EU might impose in the future under antidumping rules, countervailing duties and safeguards;

(3) uncertainty over the baseline tariffs and quotas in 77 of the UK’s trading partners which maintain Free Trade Agreements with the EU;

(4) uncertainty over special trade barriers that the US is imposing under the Trump administration.

The first two, which we shall discuss here, represent the most pressing and quantifiable sources of trade policy uncertainty facing firms in the UK following statements by both the UK and EU that “no deal” is a realistic potential outcome.

Regarding the first source of uncertainty, our starting point is that the UK is a full member of the WTO and has the right to remain a member of the WTO after leaving the EU. Therefore, the highest possible import tariffs that firms in the UK will face to export to the EU in a “no deal” scenario are determined by the EU’s WTO commitments. This means that some products will be able to enter the EU tariff-free, but others might be subject to high tariffs or restrictive quotas.

Turning to the second point of uncertainty, we observe that around the world, members of FTAs frequently use anti-dumping duties against one another – thus, the UK could easily become the target of antidumping duties into the EU.

This is not as far-fetched as it sounds: the EU is one of the most active users of trade remedies in the world, with 8.1 per cent of imported products subject to a trade remedy over 1995-2013. Moreover, high income countries frequently target each other with these import policies.

Currently, the US restricts imports of British steel wire rod because a 2016 US investigation found that British firms were dumping steel in the US market, while a major concern for the UK today is the US anti-subsidy tariff against Bombadier jets from Canada, which will hit UK exports of aircraft wings.

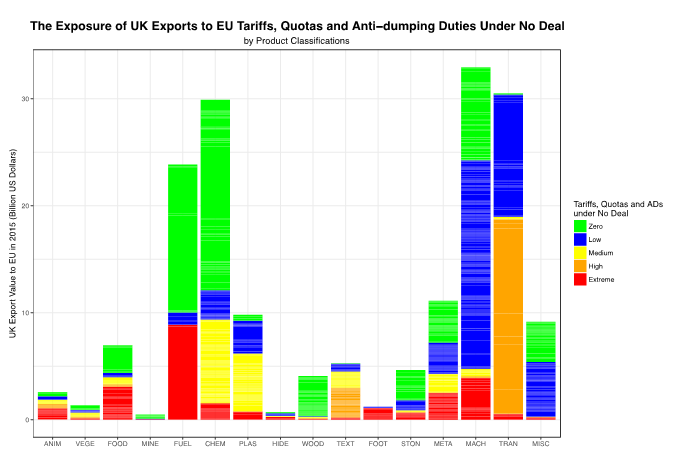

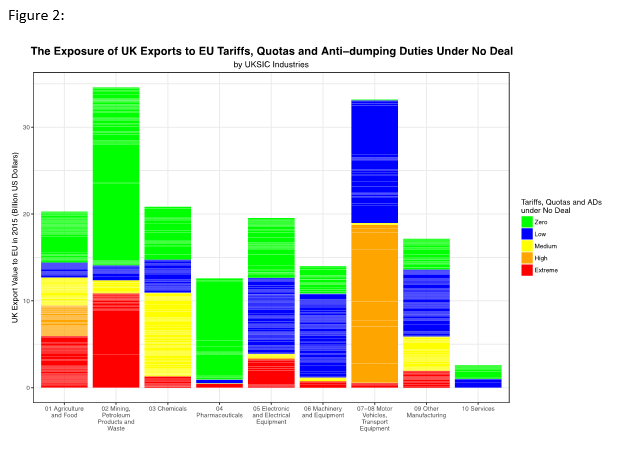

Figures 1 and 2 use data from the WTO and the World Bank on product-level tariffs, quotas and trade remedy measures along with trade flow data from UN Comtrade to quantify the trade policy uncertainty facing firms exporting from Britain to the EU. We use data on UK exports to the EU in 2015 and provide two granular breakdowns of this trade policy risk. In figure 1, we provide a breakdown based on product classification (the acronyms are provided in Table A). In figure 2, we organise the same information into UK Standard Industrial Classifications to show which industries are most exposed.

Figure 1:

To start with the good news, we calculate that 34 per cent of UK exports to the EU will remain tariff free under a “no deal” scenario, as long as the UK remains a member of the WTO. The green bars in both figures represent the value of UK exports that face no trade policy uncertainty in exporting to the EU – even under a “no deal” Brexit, these exports will pay no tariffs and face no quantitative restrictions in the EU.

From figure 1, we can see that these tariff-free exports are largely in fuels and chemicals. Figure 2 refines the large chemical product group into chemicals and pharmaceuticals and shows that most pharmaceutical exports will enter the EU duty-free even if the UK leaves the EU without a deal.

Similarly, blue bars quantify the value of exports that face low uncertainty – worst-case scenario tariffs of 1-5 per cent ad valorem. Concern rises for yellow exports where tariffs could rise to 5-10 per cent. The UK’s main concern comes from the orange exports suffering high uncertainty with EU tariffs that could rise to 11-15 per cent and the red exports exposed to extreme levels of trade policy uncertainty – a worst case ad valorem tariff over 15 per cent or the imposition of a quota or an EU trade remedy.

The bad news is that 27 per cent of UK exports face high or extreme trade policy barriers in a “no deal” scenario (this is represented by the sum of the orange and red bars in the figures). Products facing a risk of high or extreme trade policy barriers are predominantly concentrated in high-skilled and technologically advanced manufactured products including transportation equipment and machinery. There is also considerable risk facing one of the UK’s environmentally-friendly exports – biodiesel – a high-value export that has been the target of EU anti-dumping activity.

In summary, if the UK leaves the EU with no trade deal, firms in the UK will face significant policy barriers to export to the EU across a wide range of products. Under a “no deal” scenario, $47 billion of UK exports to the EU would face high or extreme tariffs, quotas or anti-dumping duties. If the UK chooses to leave the Customs Union and attempts to negotiate a bespoke trade deal with the EU, then these products should be the priority in the trade negotiations.

Table A: Acronyms from Figure 1

| Acronym | Industry | Harmonized System Sections |

| ANIM | Animal products, live animals | 01-05 |

| VEGE | Vegetable products | 06-15 |

| FOOD | Prepared foodstuffs, beverages, spirits, tobacco, edible oils | 16-24 |

| MINE | Mineral products | 25-26 |

| FUEL | Mineral fuels | 27 |

| CHEM | Chemicals | 28-38 |

| PLAS | Plastics and rubber | 39-40 |

| HIDE | Hides, skins, leather, etc | 41-43 |

| WOOD | Wood and articles of wood, pulp, and paper | 44-49 |

| TEXT | Textiles, fibers, apparel, etc. | 50-63 |

| FOOT | Footwear, headgear, umbrellas, etc. | 64-67 |

| STON | Stone, cement, plaster, ceramics, glassware, etc. | 68-71 |

| META | Base metals and articles of base metal | 72-83 |

| MACH | Machinery, mechanical appliances, electrical equipment | 84-85 |

| TRAN | Transportation: vehicles, aircraft, vessels | 86-89 |

| MISC | Miscellaneous | 90-97 |