It is the talk of British political Twitter and second place on the Sunday Times bestseller list. Professor Matthew Goodwin’s new book Values, Voice and Virtue: The New British Politics is hot property.

I should start by saying that I’ve long admired Goodwin as both an insightful author and a trendsetting ‘entrepreneurial academic’, combining his scholarly work with writing punchy op-eds and making his case on TV and radio. He’s also been personally very helpful to me and is someone I regard a good friend.

There is much I agree with in his latest book, including his central thesis that progressive liberals have a disproportionate level of presence in some of our public institutions. This results in the kinds of absurdities where extreme right-wing cases outstrip Islamist-related cases when it comes to radicalisation risks referred to the Government’s anti-terrorism Prevent scheme – even though the principal terror threat in the UK is very much Islamist extremism.

Likewise, there is a movement in the education sector which seeks to ‘decolonise’ the curriculum in our schools – which is code for portraying Britain as a historical villain wherever possible. In the NHS, we have seen the championing of pro-BLM material and blogs lecturing Brits about ‘white privilege’.

And nowhere is the intrusion of US-style identity politics more prevalent than in Goodwin’s own field of academia, where ultra-Wokery thrives and conservative academics are few and far between. In this sense, Goodwin – who holds a professorship at the University of Kent – should be commended for sticking his head above the parapet.

He’s also right to emphasise that this isn’t just irritating culture war flummery, but a serious issue of the public becoming more and more distant from those meant to represent them. That undercurrent of disaffection and anti-politics sentiment in turn means people will turn to radical alternatives.

Who are the ‘new elite’?

Much of this important debate has been lost, however, in an online debate about Goodwin’s book that has focused almost exclusively on the idea of a ‘new elite’.

As he tells it, there is a cadre of metropolitan progressives who shape much of our national conversation, and do so in a way that either excludes or actively belittles the views of working-class communities who already find themselves on the margins, often battered by the forces of globalisation. This group of largely middle class Russell Group graduates wields ‘enormous power, influential and control over the country and its institutions’. They are financially secure white-collar types in the professional and managerial classes who are tied together by their ‘strongly liberal cosmopolitan or radically progressive values’.

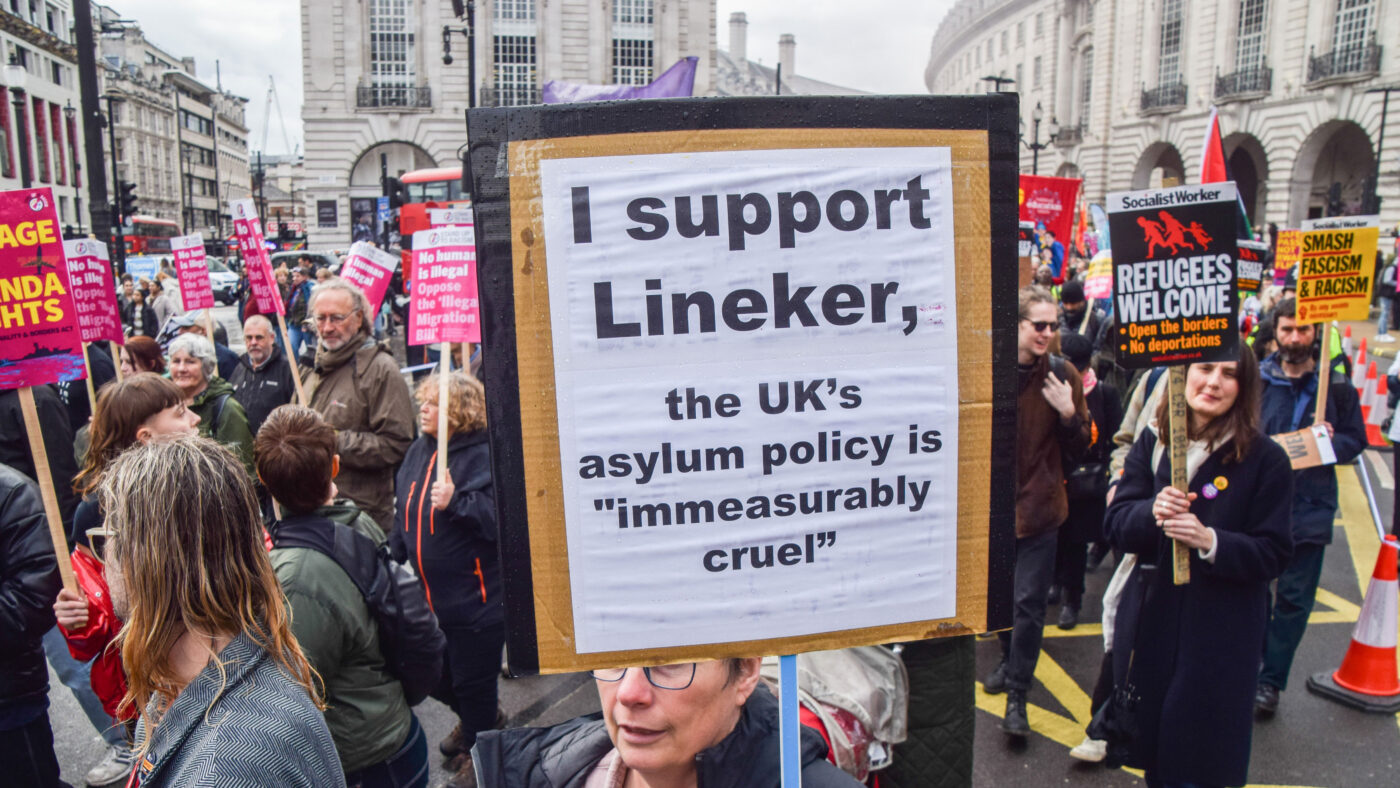

So far, so understandable. It seems plain to me that there is a group of well-off people, extending from the professional managerial class to well-known celebrities, who have the luxury of supporting exceptionally liberal policies – especially on issues like immigration and asylum – while being entirely insulated from their economic, social and cultural effects. The recent Gary Lineker ‘1930s Germany’ row was a perfect encapsulation of this phenomenon. And like many people, I find these people insufferable: sanctimonious, smug but almost completely unsympathetic to the concerns of their own compatriots, so often glibly dismissed as ‘Little Englanders’ with backwards views.

Where I do take issue with Goodwin, however, is the idea that there is a coherent group that wields a huge amount of cultural power and shape conversations on a national level.

Looking at some examples of ‘new elitists’ in Goodwin’s own recent articles, they include everyone from Carol Vorderman to Emily Maitlis, Jon Sopel, Mehdi Hasan, and Sam Freedman. While Vorderman is a bona fide celebrity, and Maitlis and Sopel are certainly well known, Hasan and Freedman are very far indeed from being household names. Hasan is not even based in Britain. Freedman himself has joked that he isn’t even the best known person in his own family, never mind among the wider British public. They might all be able to rack up retweets and Likes on Twitter, but have they really hijacked Britain’s national conversation?

Getting fixated on a largely middle-age, well-off metropolitan ‘elite’ also risks obscuring a broader, more serious problem. In my view the reason our institutions often suffer from progressive-liberal biases is not just the managerial class, but the views of their younger colleagues: younger, disgruntled, degree-educated staff desperate to exert cultural influence in order to compensate for their lack of socio-economic resources.

For while the cult of ‘Wokeness’ is undoubtedly an exercise in exerting cultural influence, it’s one that ultimately stems not from strength, but economic powerlessness. For many younger people, an expensive degree has not secured the kind of income or lifestyle they originally anticipated, while traditional markers of socio-economic status such as home ownership are a distant dream. Is it any surprise that many cleave to an identitarian ideology that maintains that the world is a thoroughly unjust place, riddled with prejudice and inequality?

More galling still for younger Brits, the ‘gammons’ and ‘thickos’ in the provinces who have worked in skilled trades most of their lives have often ended up owning their own homes, and have made their voices heard politically in both the 2016 referendum and the 2019 general election.

Equally disappointing for the decolonisers and social media poseurs is that for all their endless rhetoric about injustice and racial disparities, Britain stubbornly continues to be one of the world’s most successful multi-ethnic democracies. Indeed, a new study shows that residential segregation along ethnic lines is at an all-time low in England and Wales. Interestingly, according to the authors, this is something that has happened organically, ‘without major government interventions on integration’.

The biggest issue facing Britain, to my mind, is not inter-racial strife, but the fraying of the contract between the generations. We now have a deluge of young, embittered, progressive-minded graduates faced with impossibly high housing costs, inflation and an atmosphere of near-constant economic gloom. They are seeing a Labour Party once led by Jeremy Corbyn adopt increasingly small C conservative positions on immigration, crime and national security ahead of the next election. Nor does Keir Starmer even include housebuilding as one of his five ‘missions’ for Britain, despite a recent Centre for Cities report stating that the UK has a backlog of 4.3 million missing homes.

So while Goodwin may well be onto something when he refers to a ‘serious and far-reaching rebellion’, we shouldn’t rule out that the rebellion will come not from the populist right, but from the progressive, disenfranchised left.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.