First drafts of history are sometimes wrong. According to the results of the British Election Survey, the most authoritative study of voting patterns in UK elections, there is one big mistake in the first draft of what happened on June 8, 2017. The youthquake – the surge in turnout among young voters that supposedly deprived Theresa May of her majority – never actually happened.

The youthquake theory started with a constituency-by-constituency correlation: seats with younger electorates were, generally speaking, experiencing increases in turnout from 2015 to 2017. The not unreasonable assumption, then, was that young voters were turning out – and overwhelmingly voting Labour – in a way almost no one had anticipated. That assumption was reinforced by vivid anecdotal evidence: the crowd at a Labour party rally is younger than Labour voters in general; chants of “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn” at Glastonbury made the youthquake theory seem watertight.

But, as the BES team explain, all that aggregate constituency data told us was that there was a big turnout in the types of places where young people tend to live – i.e. cities. In fact, the British Election Survey findings suggest that the relationship ends there. According to their numbers, there has been no meaningful increase in turnout among 18-25 year olds.

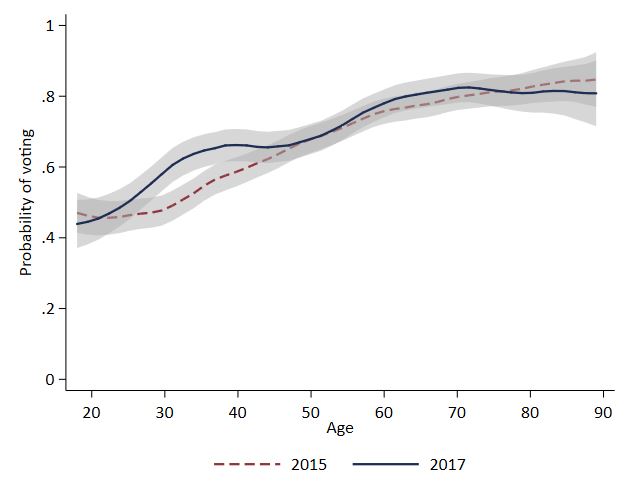

And, as the chart below shows, the demographic where there really was an uptick in turnout was for voters in their thirties, a far cry from the caricature of the indebted student who thinks Jeremy Corbyn is “the absolute boy”. And, in general, the BES team say that “none of these changes are statistically significant”.

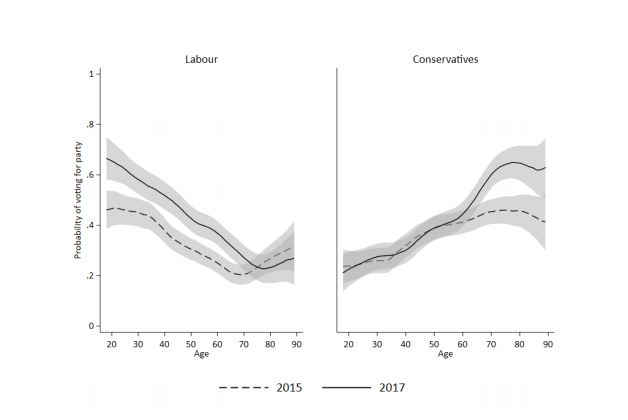

The survey results are a chastening reminder not to get to get carried away with narratives that, before we really know if they are right or not, can very quickly build up a head of steam. Even the ones that are true soon become misleading exaggerations. These days the stereotypical Labour voter is young. As is the stereotypical non-voter. But only 12 per cent of Labour voters in 2017 were under the age of 25, while at least four in five non-voters were over the age of 25.

Political commentators and even politicians themselves have made the same mistake when it comes to Brexit. Trends that show certain parts of the country lent a certain way in the EU referendum have become misleading caricatures: a bitter and left-behind Brexitland at odds with cosmopolitan and content urban Remainers. This account squeezes out all nuance and writes millions of voters out of the story. What do we know about the Leave voters of North London? Or the Remainers of Skegness?

No one saw last year’s election result coming. There is a natural temptation to think that a remarkable outcome must have a remarkable cause, such as a huge surge in young voter turnout. But, according to the BES, the “explanation for the large increase in Labour’s vote share is more prosaic – Labour increased its share of the vote across a wide spectrum of the electorate.”

Does the youthquake mistake mean Conservative are wrong to be so worried about what they are offering young voters on tuition fees and housing? The short answer is no. Even if there was no surge in turnout among young voters, the Conservatives lost ground among young voters at the last election. And polling since the election suggests that trend has continued. Youthquake or otherwise, the party writes off younger voters at its peril. And so the efforts of its more thoughtful Tories to ask hard questions about why the young take such a dim view of their party are as important as ever.

The big picture for the Conservatives is more heartening now the young voter surge theory has been disproved. The thing about Jeremy Corbyn that had Tory MPs so worried immediately after the election wasn’t only that he had massively outperformed expectations, but that in mobilising a previously ignored cohort of young voters that he now had at his disposal, he had changed the rules of the game. If there was no youthquake then that simply wasn’t the case.

The further away from it we get, the less remarkable the 2017 general election appears. Yes, the result caught everyone by surprise and transformed the fates of the two main party leaders involved. But, with the important exception of Brexit, which clearly realigned votes in a way that hurt the Conservatives, the causes of that result are nothing new: a tired-looking incumbent party, Labour promising popular policies, the Conservatives failing to do so, one side fighting a better campaign than the other. In other words, the Conservatives got just about everything wrong and still won.