The struggle for women’s liberation is often framed in terms of the campaign to secure the vote in the early years of the 20th century. Less heralded is the way women in several Western nations acquired property rights in the middle decades of the 19th century.

Prior to that, the system of ‘coverture’ meant a woman transferred all her cash, bank deposits and any other moveable property to her husband upon marriage. Although she could own a house or some land, her husband was entitled to rent it and keep the profit.

The moral case for ending such an arrangement needs little explaining, but a new study shows that countries who expanded women’s property rights also saw a tangible economic benefit.

As academics Moshe Hazan, David Weiss, Hosny Zoabi explain, the discrimination of coverture had serious economic as well as social consequences:

Consider the perverse incentives that coverture created. It would have been imprudent for a single woman to put money in a bank, or to hold any other asset except real property, because her future husband would simply take it away from her. Parents who wanted to give their daughters gifts or bequests would have been equally hesitant to put money in a bank, and would have used real estate instead.

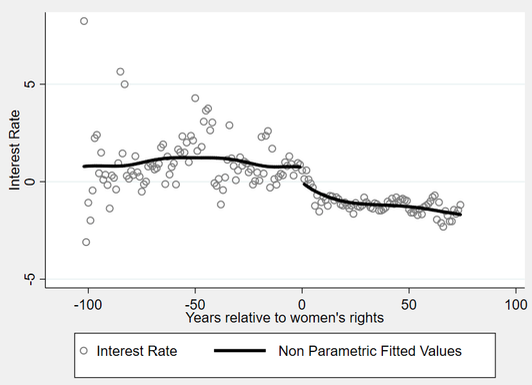

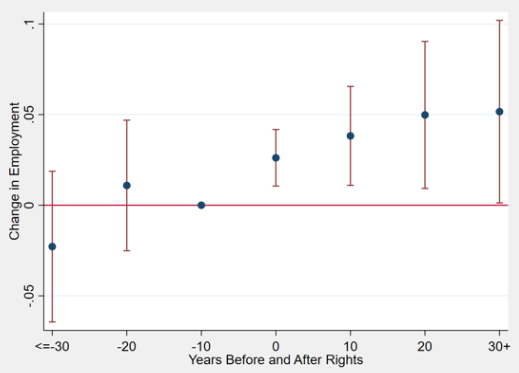

The trio’s research of the United States in the period before and after the end of coverture shows that enhancing the status of women galvanised the American economy. As the graph below shows, In states where women had more property rights, bank deposits and loans both grew, while interest rates fell.

The knock-on effect of lower interest rates and more money being loaned out, according to the trio, was an increase in industrialisation. That meant that the beneficiaries of non-discrimination were not just women, who now had more control over their own finances, but men who moved from punishing agricultural work into slightly less punishing and better paid industrial jobs.

None of this should come as any great surprise. As the likes of Paul Romer have shown, developing human capital is a crucial element of sustained economic success. That has profound implications for discrimination. Certainly, we ought to end unequal treatment as a moral affront. But a less discriminatory society is also one in which a greater number of people are able to realise their potential, to develop their human capital, which enriches us all.

This is another example of the way in which liberal social policies based on the rule of law are the handmaiden of successful economies. It’s certainly possible for a country to become wealthy without treating all its citizens equitably, but as the research above amply demonstrates, doing so is much quicker and easier when everyone gets a fair crack of the whip.

And while much of the discourse about the future focuses on the risks and opportunities of various tech panaceas — AI, automation, robots and so on — for the 40 per cent of countries where women still do not enjoy full property rights, there are easy economic wins just waiting to be realised.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.