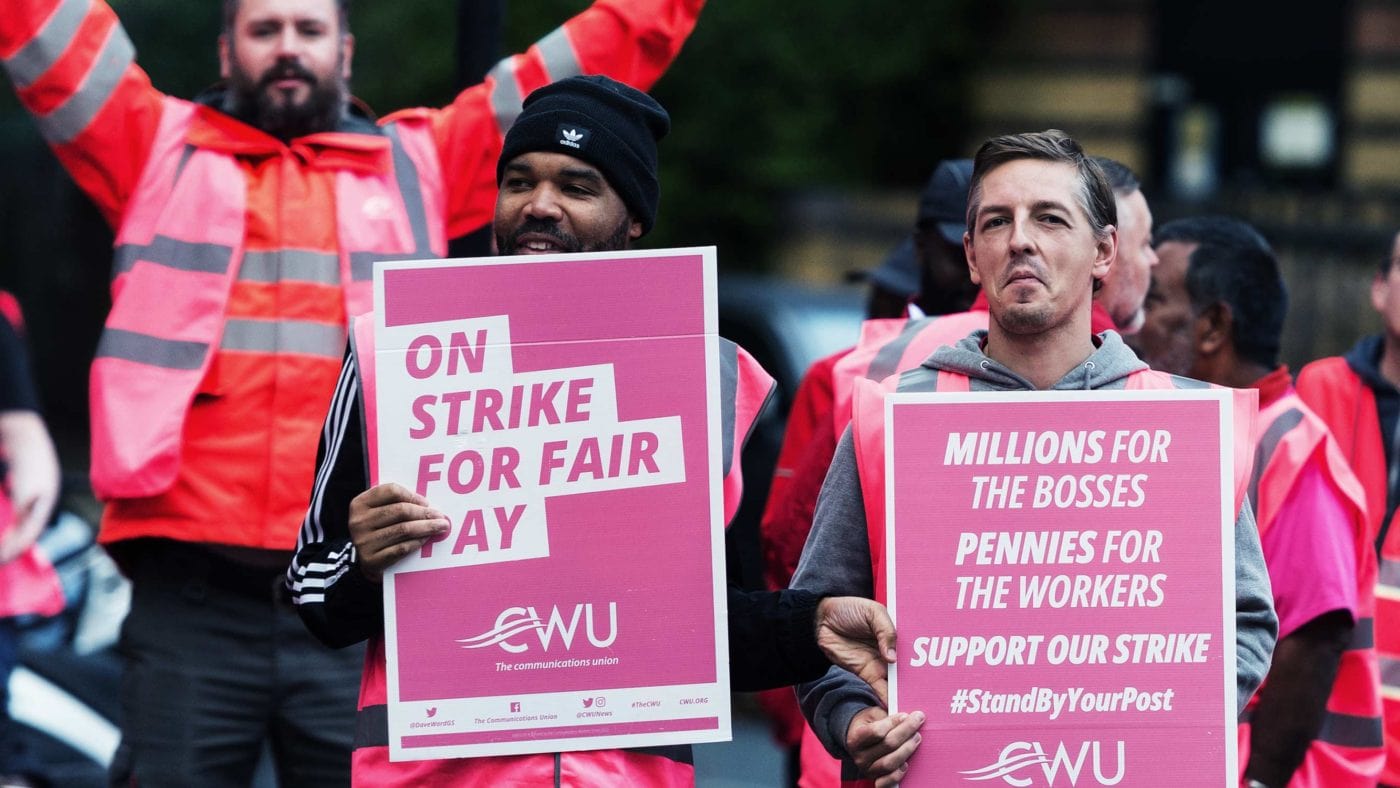

With a new government, the Queen’s death and now the Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget, industrial unrest has not been in the headlines much recently – but a month ago the explosion of strikes was on all our minds.

And there’s much, much more to come as we head into winter. Nineteen days of strike action are planned for Royal Mail between now and Christmas. There’s an eight-day strike beginning at the port of Felixstowe, while similar action at Liverpool is in its second week. UNISON is going to bring out university support staff. A London bus strike may have been called off, but four more days of bus strikes have been announced in Kent. Scottish NHS staff are considering action. Tories heading to Birmingham for their annual conference will be reminded that the long-running strikes on the railways are continuing, with the three big rail unions now being joined by Unite, which organises Great Western Railways engineers.

A common feature of this wave of militancy is a demand for inflation-busting pay increases, with little willingness to consider changes in working arrangements to increase productivity. Those kinds of reforms are the only sustainable way to boost pay – something everybody wants to see.

Though there has been sporadic industrial action in the last decade, we’ve not seen anything on this scale for a long time. Today’s ministers have no experience of handling disputes which in many cases are squarely aimed at their government. There has even been over-excited talk of a general strike to bring down the Government; Now, that would be illegal, and the TUC would never give the idea the time of day – but even loosely synchronised strikes will increase the pressure on what is already, just three weeks in, a beleaguered administration. It all adds to the general mood of crisis.

However, the new government is more likely to fight back against union militancy than some of its predecessors. Back in July, the relevant section of the 2003 Employment Agencies regulations was repealed, allowing employers to draft agency workers in to cover for striking workers. Around the same time, when he was still Business Secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng vetoed plans for electronic strike ballots, which were thought likely to encourage more industrial action.

Last week, Mr Kwarteng announced that unions would soon be obliged to put pay offers to members during negotiations. He also reaffirmed the Conservatives’ commitment, spelt out in the 2019 manifesto, to require transport unions to maintain a minimum level of service. Although this has not yet been announced as policy, Liz Truss also indicated during the leadership campaign that she would support raising the voting threshold for strike action – perhaps to insist that 50% of the entire workforce must vote in favour before a strike can take place.

Such proposals have predictably outraged the unions and their political supporters, who see the right to strike as a fundamental human right. Maybe so, but it is a right which has always been circumscribed, even in the most liberal of liberal democracies. Some of the measures proposed are common in other countries; for example, minimum service agreements exist in Spain, France and Italy. We ban outright strikes in the armed forces and the police; Germany, Poland, Denmark and Estonia ban strikes by many types of public employees including university teachers, firefighters and health and social care workers. Compulsory arbitration has been required in Australia and Canada; at one time Boris Johnson wanted it for London’s transport system. Where to draw the line on strike restrictions is seems pretty arbitrary.

Leaving theoretical principles aside, a more pragmatic question is this: will the proposed measures work in limiting or reducing strike action? A recurrent problem is politicians naïvely believing that passing a law against something will stop that thing happening. Changing laws simply changes behaviour. In the case of laws against strikes, unions are not passive. They will think of ways round restrictions to achieve their goals.

Take for example, the fashion for one-day strikes, which has been so successful at maximising disruption on the railways (by messing up services before and after strike days because of rostering and timetable complexities) at minimum cost to workers’ incomes. One-day strikes also make it much harder to replace strikers with agency workers. While an old-style months-long strike of the kind we used to see in the past might make it worthwhile to train up and bring in replacement workers, one-day strikes, often arranged at fairly short notice, are quite another matter. The effort and cost involved are just not worth it.

I also have doubts whether the minimum service agreements would add very much to the Government’s anti-strike arsenal. Although there may be such laws on the statute book in a number of countries, there is little published evidence on how they work in practice.

A figure of 20% service coverage has been bandied around for the UK. However, that level is sometimes already reached during bus, train and tube strikes, as non-strikers and management manage to keep things moving. More to the point, a stripped-down service is not much use to anyone who wishes to make a complicated cross-country journey or be sure of getting back home after a night in town.

The plan to get union members to vote on pay offers is more promising, though we need to know more about how this would be done, at what stage of negotiation, how a new offer would be treated and so on. Organising a ballot – maybe several ballots – might paradoxically add to the length of time a dispute continued, and a firm rejection of an offer might strengthen the resolve of negotiators when they might otherwise have reached a compromise.

It may be worth persisting with these measures, whether or not they are particularly effective, simply as a statement of intent, to stake out a firm position that the Government will not back down in the face of union militancy, and to encourage private sector employers – who may take their cue from government – to resist unreasonable demands. Private business decisions, however, depend on a company’s own circumstances and we should not drift into an informal 70s-style incomes policy where private employers are pressured to toe the Government’s line.

It remains to be seen whether current levels of strike activity are the product of a particular cluster of factors – the end of Covid restrictions, the cost of living crisis, a febrile political situation – or whether they are likely to persist year after year.

If unions persist in a political turn, and resist proposals for modernising working practices, I suspect, the Government will need more than the current proposals to face them down – perhaps outright strike bans in some areas, compulsory arbitration in others. A project to boost economic growth cannot afford to revert to the industrial relations environment of the past.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.