Donald Trump has repeatedly lamented the supposed decline of the American manufacturing sector. On the campaign trail, he asserted that Americans “don’t make anything anymore” and pledged “to restore manufacturing in the United States.” Yet there is no reason to think of manufacturing jobs as the gold standard in employment. The nature of work has been changing for about 250 years and it is likely to continue to evolve – thanks to declining birth rates and the rise of robotics and artificial intelligence – in the future.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, between 80 and 90 percent of the world’s population worked in agriculture. At the start of the 19th century, people in Western Europe and North America began to move into manufacturing jobs en masse. Factory jobs were not universally welcome. Factory jobs were criticised by philosophers, like Karl Marx, lampooned by comedians, and bemoaned by poets, like William Blake.

Marx felt that the factory production, in which products are generated using an endless sequence of discrete and repetitive motions, did not offer the worker enough psychological satisfaction. The worker, who did not design or market the product, was thus “alienated” from the latter. Chaplin turned the soul-and-body crushing assembly line mode of production into a hilarious comedy skit in his 1936 movie, Modern Times.

And, who can forget William Blake’s 1808 poem “Jerusalem”, in which the artist mourns the “satanic mills” that in his view pockmarked the bucolic face of the English countryside?

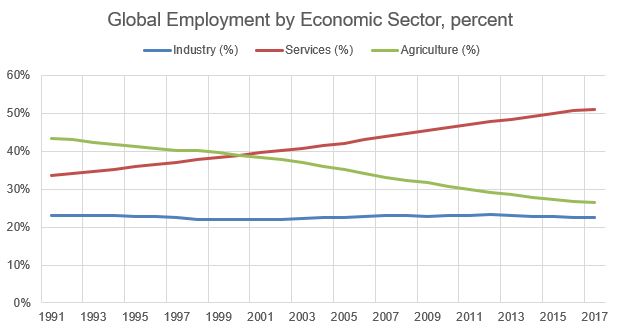

Today, we know that most people moved from agricultural work in the countryside to factory work in the cities willingly, for the latter provided higher wages, and greater independence and cultural stimulation. This trend continues to this day. Between 1991 and 2017, for example, agricultural employment fell from 43 to 27 per cent of the global workforce. Only in very poor countries, such as Bhutan and Zimbabwe, does agriculture continue to employ over 50 per cent of labourers.

In the United States, employment in the manufacturing sector continued to grow until the middle of the 20th century. In 1950, for example, manufacturing employed approximately 35 percent of all workers. Fifty years later, it employed only 15 per cent of all workers. Conversely, the share of workers employed in the service sector increased from approximately 18 percent in 1960 to almost 80 per cent in 2000. Similar trends can be observed in other advanced economies, such as the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan.

Meanwhile, manufacturing jobs have grown in countries that embraced industrialisation in more recent decades. Between 1991 and 2017, for example, industrial employment rose from 12 to 19 percent in Bangladesh, from 19 to 24 percent in China, from 15 to 25 percent in India and from 9 to 23 percent in Vietnam. History suggests that, as these populous and rapidly industrialising countries become richer, the service sector will play an increasingly prominent part in their economic development.

Are these employment trends from agriculture to manufacturing to services cause for worry? Far from it! The service sector consists of jobs in the information sector, investment services, technical and scientific services, healthcare and social assistance services, as well as arts, entertainment, and recreation services. Most of these jobs are less physically arduous, more intellectually stimulating and better paid than either agricultural or manufacturing jobs.

They are, also, less dangerous. In 2014, global fatality rates per 100,000 employees in agriculture ranged from 7.8 deaths in high-income countries to 27.5 deaths in South-East Asia and Western Pacific. In manufacturing, the range was from 3.8 in high-income countries to 21.1 in Africa. The range for the service sector was from 1.5 in high-income countries to 17.7 in Africa.

The evolution of the workplace is far from finished. With fully mechanised farms on the horizon, agricultural employment in advanced countries is heading toward zero. Similarly, the rise of the robots and artificial intelligence are likely to displace tens of millions of manufacturing and service sector workers in rich countries.

Collapsing fertility rates in rich countries, however, will likely prevent the emergence of mass unemployment. Moreover, high levels of human capital and relative openness of advanced economies are likely to unleash innovation in unexpected ways, thus soaking up displaced workers.

The employment picture is less sanguine in some poor countries. That’s especially true of Africa, the population of which is projected to go on expanding well into the 22nd century. Scandalously mismanaged state education systems retard development of human capital and lack of economic freedom, especially rigid labour markets, make African countries ill-positioned to respond to the challenges of automation.

Will the millions of young Africans without a prospect for meaningful employment force change upon their sclerotic governments or opt to migrate out of the continent? Time will tell.