The England that AJP Taylor wrote about in the introduction to English History, 1914-1945 is a very different country:

‘Until August 1914 a sensible, law-abiding Englishman could pass through life and hardly notice the existence of the state, beyond the post office and the policeman. He could live where he liked and as he liked… He paid taxes on a modest scale: nearly £200 million in 1913-14, or rather less than 8 per cent of the national income. … broadly speaking, the state acted only to help those who could not help themselves. It left the adult citizen alone.’

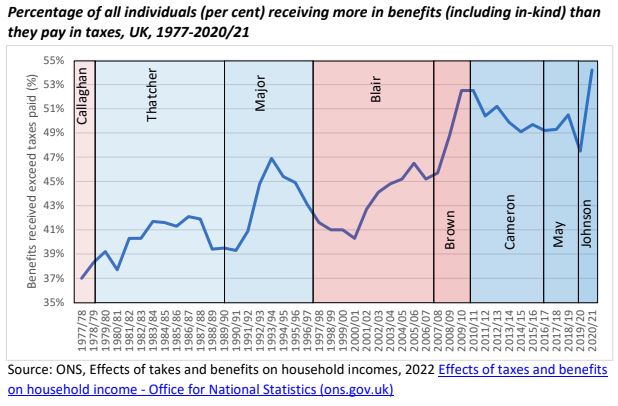

Things have changed. We now seem to expect fewer and fewer people to pay for an endlessly growing state while politicians compete to demand higher ‘investment’ (read spending). All this at a time when ONS data show that the top 10% of earners pay over half of all Income Tax (53.1%); and over half the population – 54.2% or 36 million people – now receive more from the state in benefits than they pay in tax (the ONS defines benefits as cash benefits plus benefits in kind such as the imputed value of state spending on health and education).

This dependency ratio is now at an all-time high. The upper lips of our Edwardian ancestors would twitch.

.

.

This chart shows how the dependency ratio spikes in reaction to major economic shocks: Black Wednesday in 1992, the financial crash of 2008 and Covid-19 in 2020. Yes, it can come down, as it did under John Major in the mid-1990s and Conservative ‘austerity’ in the 2010s, but the trend is clear. It is going up and up.

And things can only get worse: the impact of government measures in response to the pandemic is not fully revealed in these figures as the ONS counts the furlough payments made by the state as income, not cash benefits. Yet for almost 18 months millions of private sector workers were in effect being paid by the state.

On top of that, it is now clear that half a million people have left the workforce, probably never to return. Long-term health problems are further reducing employment, driving up the welfare bill. State pensions and Universal Credit will go up by 10% in April this year, while the Energy Price Guarantee has given every household an additional £400 in benefits. Meanwhile, NHS spending continues to increase inexorably.

All of this is paid for by fewer and fewer people. Income Tax has now become a ‘wealth tax’ by stealth: two thirds of all Income Tax is paid by a fifth of earners. These top earners pay over three times as much income tax as the bottom 60% – despite this group being six times bigger. And for the first time ever, middle-earning households now receive more on average from the state in cash benefits and benefits-in-kind than they pay in taxes.

Nor is this a sign of rising inequality: the Gini co-efficient – the main measure of income inequality – is exactly where it was in 2010. Inequality rose fastest under Tony Blair in the days when the Labour leadership was ‘intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their taxes’.

Are we happy, or even ‘intensely relaxed’, to see the dependency ratio rise and rise? Is it desirable to see more and more households dependent on the state? To what extent will this make welfare and tax reform possible? How much more of the income tax burden can the wealthy shoulder?

Yes, AJP Taylor recognised in his essay that state action had been increasing before the First World War: for since 1870, the state educated children up to the age of 13; it gave a ‘meagre’ pension for the needy over the age of 70 but that was when life expectancy was just 52; and it helped to insure some workers against sickness and unemployment. But for how much longer, now that over half of households receive more than they pay in taxes, can we see this dependency ratio increase? What will be the consequence of the dependency ratio hitting 65%? 80%?

If these numbers matter, then perhaps they should get the attention they deserve. They could, for example, become an integral part of the OBR budget forecasts; they could become part of any party’s manifesto or even their pledges; they could become the object of study for the OECD, which might monitor how the dependency ratio varies between advanced economies. But maybe, first of all, perhaps we can agree that the dependency ratio needs to be watched?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.