In my beginner’s guide to socialist economics I noted that communism, which was supposed to lead to greater equality, has in fact led to a return of feudalism.

Like feudal societies, communist societies have an aristocracy composed of the communist party members.

Like feudal societies, communist societies have a population of serfs with limited or no rights and little possibility of social mobility.

Like feudal societies, communist societies are held together by brute force.

As if to prove me right, The Daily Mirror, has just released footage from North Korea’s northeast province of Ryanggang, where hundreds of children can be seen breaking and carrying rocks during construction of a local railway.

The children are eight or nine years old and work up to 10 hours a day in the heat of the blazing sun. Neither they nor their parents are compensated for this back-breaking labour.

[The image is provided courtesy of The Daily Mirror]

As the newspaper points out, these are the children of North Korea’s working class. Familiar class stratification has emerged in North Korea, with the communist party and the government employees at the top, and the underclass at the bottom.

The children of the former attend newly-constructed schools and enjoy, as much as they can in the Hermit Kingdom, a semblance of a normal life. The latter are barely surviving in a state of abject poverty and servitude. So much, then, for the communist commitment to equality.

In the Daily Mirror footage:

“In one film … a forlorn lad of around eight or nine, wearing an England football shirt, is ordered to break rocks at a cliff face. Girls pair up as they struggle to lift heavy loads into piles. One young boy winces under the strain of his work. Teachers shielding their faces from the glaring midday sun bark orders at other youngsters bent double from lugging sacks as big as their bodies. Mounds of massive sandstone broken up by the dusty child slaves can be seen piled high.”

It is worth noting that child labour was once a completely unobjectionable part of human existence. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, which started in Great Britain in the late 18th century, no society thought twice of eschewing child labour. As Johan Norberg noted in his book Progress, “Prior to the mid-19th century it was common for working-class children to start working from seven years of age.”

It is, therefore, somewhat ironic that child labour should come to be so closely associated with the process of industrialisation – a topic well worth exploring in greater depth below.

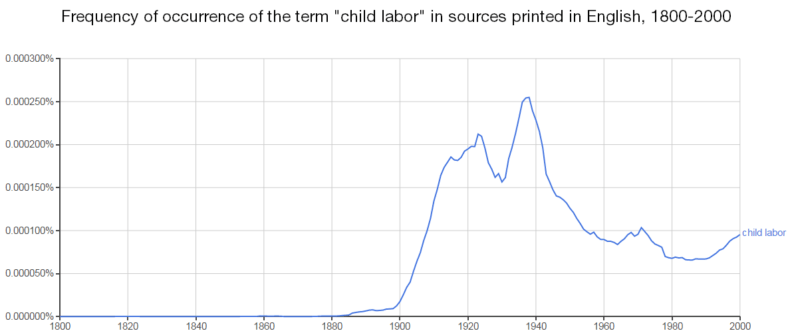

As the chart above illustrates, people did not write about child labour prior to the 19th century, because working children were so ubiquitous. Prior to industrialisation, which massively increased productivity of the farm, there were no food “surpluses.” All of the food that the farm produced was consumed by the peasant families and their beasts of burden.

An idle child or, for that matter, an idle man, woman or donkey, was a waste of precious resources. “The survival of the family demanded that everybody contributed,” writes Norberg.

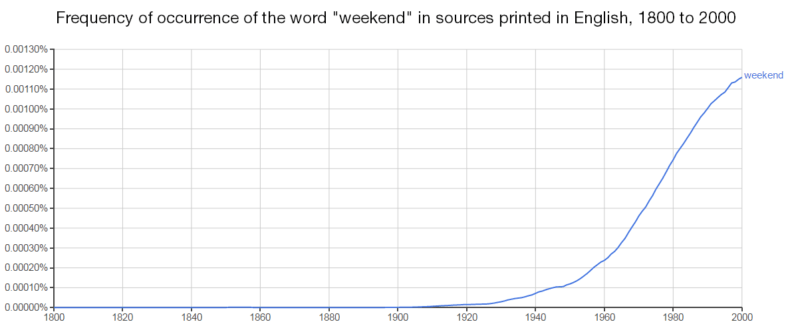

Bemoaning child labour, in other words, made about as much sense as complaining about a lack of plans for the weekend—since most people worked at least six days a week. It was industrialisation that changed all that.

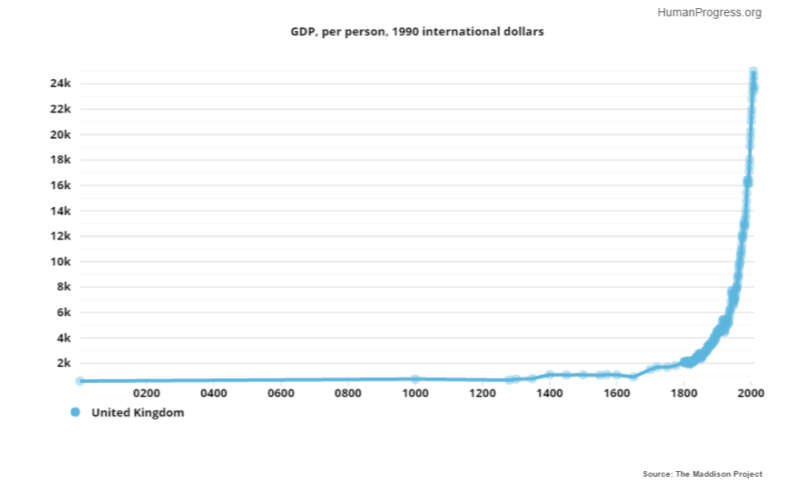

As farm productivity increased, people no longer had to stay on the farm and grow their food. They moved to the cities in search of a better life. At first, living conditions were dire. Medieval cities were not prepared for the influx of millions of people from the countryside. Slums arose and disease spread.

By the mid-19th century, however, living and working conditions started to improve. Economic expansion led to an increased competition for labour and wages grew. That, in turn, enabled more parents to forego their children’s labour and send them to school instead.

It is crucial to remember that it was only after a critical mass of children stopped working that people realised that life without child labour was possible. Legislation limiting child labour got more stringent as the 19th century progressed, but it was not until the Factory and Workshop Act of 1878 that the British Parliament banned labour for children less than 10 years of age and required that all children under 10 receive compulsory education.

Over the course of the 20th century, prosperity spread to other parts of the world. Today, child labour in Asia and Latin America are at an all-time low. It remains a problem in Africa, large parts of which remain stuck in the subsistence economy.

It flourishes in North Korea – a modern slave-state that, in the pursuit of communism, has returned its children to an impoverished, servile working class.