Public trust in the Chief Medical Officer, Chris Whitty, may have taken a knock during the pandemic, but the Government was fortunate to have a relative unknown in the post when the daily briefings began in March. How much worse it would have been for the credibility of official health advice if his predecessor, Professor Dame Sally Davies, had still been in charge.

By the time Dame Sally finally passed the baton onto Whitty last autumn, she had become a risible figure. Dubbed the ‘nanny-in-chief’ by the media, she falsely claimed that the health benefits of moderate drinking were an “old wives’ tale” and urged women to think of breast cancer every time they picked up a glass of wine. She declared herself “aghast to read about how crisp packet sizes have increased” (they haven’t) and complained that “food is everywhere”. She consistently opposed e-cigarettes and wanted vaping banned indoors, thereby putting herself on the wrong side of the most significant health argument of her day. She compared obesity to terrorism and called for taxes on various food products.

The press delighted in finding evidence of her hypocrisy, whether it was receipts for sugary treats in her expenses claims or signs of boozing in her Facebook pics. Although she claimed to get off the bus two stops early to nudge her into walking, it was revealed that she spent £5,000 a year on taxis, including for journeys that could easily be made on foot.

Shortly after leaving the post, Dame Sally took her nanny statism to comical extremes, demanding a ban on food consumption on public transport, banning restaurants from calling themselves restaurants if they sold food of which she disapproved, and putting any food deemed to be high in salt, sugar or fat in plain packaging. To the media, she reiterated her unfounded but longstanding concerns about crisp packets getting bigger.

Had Dame Sally been the face of the Government’s Covid-19 strategy, such as it was, there is a good chance the public would have assumed she was tilting at windmills again and that there was nothing to worry about. By standing down last year, she may have saved lives.

But now she’s back and doing interviews again. Having held the most senior role in public health between 2010 and 2019, she clearly has questions to answer. Why was so little PPE stockpiled? Why did we plan for an influenza epidemic and not a SARS epidemic? Why could our test-and-trace system only cope with five coronavirus cases per week in March?

Judging by her interview with Times Radio at the weekend, Dame Sally would rather talk about issues closer to her heart. With a book out later this week, she was singing her greatest hits, blaming the UK’s relatively high rate of Covid mortality on “our structural environment to which advertising, portion size, and many other things come into play”. She claimed that food portion sizes have increased “immensely” and asserted that: “There is a direct correlation between between obesity and a high mortality for Covid”.

Studies showing a link between obesity and Covid mortality have given her a life raft and by God is she clinging to it.

Has she got a point? It is true that ‘people living with obesity’ (to use the latest PC terminology) are over-represented in both the Covid wards and the Covid mortality figures. Studies suggest that obesity increases the risk of Covid death by about a quarter, roughly equivalent to the risk of being male.

However, the biggest risk factor for dying of Covid-19 is being very old and, for obvious reasons, the morbidly obese are unlikely to be very old. The overall impact of obesity on Covid-related mortality is therefore marginal. When the BBC’s fact-checking show More or Less looked at the issue in August, they estimated that if Britain had the same obesity rate as the EU average, it would have had 600 fewer deaths, and if it had the same (low) level of obesity as Italy, it would have had 1,300 fewer deaths.

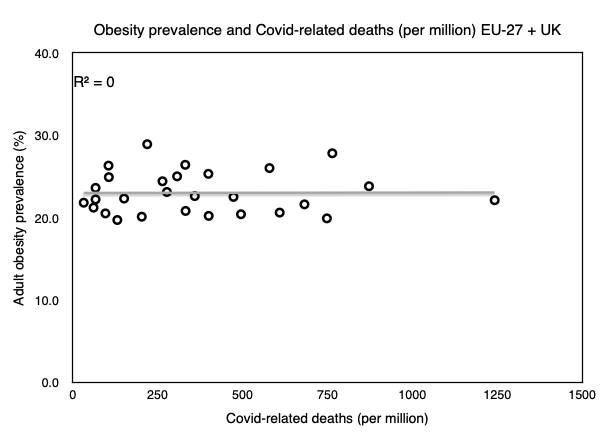

Britain’s relatively high rate of obesity therefore explains only about 1%-2% of its Covid death toll. Given the different ways in which each country counts Covid deaths, this is a rounding error. If we chart obesity rates and Covid mortality rates on a graph, there is a perfect absence of “a direct correlation between between obesity and a high mortality for Covid”.

The same type of evidence that found obese people to be more likely to die from Covid-19 also found that people who smoke are less likely to be infected with the coronavirus. Furthermore, in contrast with obesity, when researchers compare the smoking rates of European countries with Covid-related mortality, they find “a negative association between smoking prevalence and COVID-19 occurrence at the population level”. Sally Davies ignores this inconvenient fact and simply asserts that: “We know if we were slimmer as a nation, and smoked less, we would have less [Covid] mortality.”

Here we see the two defining characteristics of the modern ‘public health’ professional – the exploitation of trust in medical expertise to say whatever you want regardless of the facts, and the obsession with lifestyle factors which, in this instance, have only a modest connection to the question at hand.

The debate about which countries handled Covid-19 best will run and run. The question of why some countries did better than others is an interesting and important one. In the final analysis, obesity and smoking are unlikely to feature as significant factors. More blame-worthy is a ‘public health’ establishment, personified by Sally Davies, which spent its time worrying about crisp packets when it should have been preparing for a viral pandemic.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.