With Covid restrictions finally lifted, the country’s attention is turning from public health back to the economy. Cost of living pressures, the balance between tax, spending and debt, and the pressing need to raise Britain’s mediocre long-term growth rates are once more at the forefront of the policy debate – and rightly so.

Britain faces almighty economic and fiscal challenges. So it is worth setting out the full grim detail of the pandemic’s impact on the economy, and what it should mean for the Government’s priorities.

The economy has not quite recovered to its pre-pandemic size, the public sector finances have taken a hammering unprecedented in peacetime.

Tax rises are set to squeeze businesses and households, disincentivising investment, worsening the outlook for growth and hitting taxpayers and consumers in their wallets at the worst possible time. Meanwhile, Britain is entering into a cost of living crisis.

There is therefore a pressing need for radical policy action to boost growth, ease cost of living pressures and shore up the public finances via supply-side reforms, tax cuts and fiscal restraint.

So where are we after two years of Covid-19?

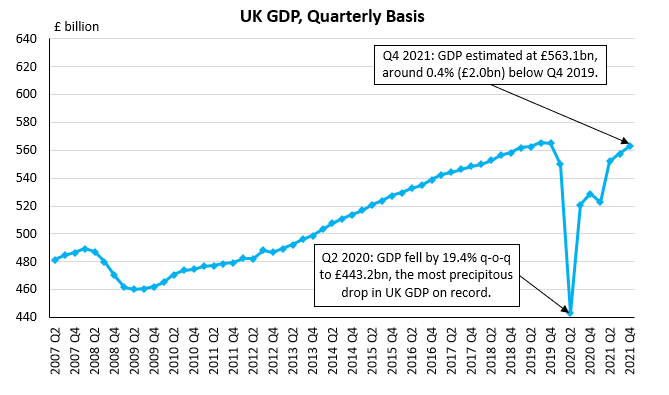

The UK economy has not quite recovered to its pre-pandemic size, and there is still a lot of lost ground to make up

According to estimates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), UK GDP in Q4 2021 was still 0.4% below its Q4 2019 level. However it remains an uncertain picture.

The emergence of the omicron variant led to renewed restrictions at the end of November, following which hospitality, travel and high street retail took another battering over the festive period (especially outside England). Overall retail sales fell by 3.1% month-on-month in December.

On the other hand, with the ‘Plan B’ restrictions lifted, the economic outlook for the immediate future seems a little more positive – even if consumer sentiment remains depressed. And it’s worth remembering the ever-present risk of a new variant emerging.

That being said, it looks likely that the economy will return to its pre-pandemic size in Q1 2022. Nevertheless, celebrations should be muted. Even getting back to the economy’s previous size represents the annihilation of over two years of economic growth, which should have added 3.6% to the size of the British economy by now, according to Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) forecasts published in early March 2020.

.

Structural changes to the UK economy are likely to have far-reaching implications for employment, productivity and GDP growth

The pandemic has brought about a radical shift in attitudes towards working from home and accelerated the shift away from the high street towards delivery services and online retail. Homeworking saw household consumption patterns shift, with spending on restaurants and hotels 38% lower in the first three quarters of 2021 than the same period in 2019, while spending on household goods and services was up by 14%.

In this environment, some sectors could end up permanently smaller. A large part of business travel is probably gone forever. And sectors such as hospitality, transport and tourism are struggling in other ways, with the record 1.25m job vacancies recorded in the October-December period partly reflecting people’s reluctance to pursue uncertain careers in at-risk sectors.

One silver lining from the pandemic is that there has not been the predicted spike in unemployment. Employment data shows unemployment spiking following the ending of furlough, as many businesses and jobs proved unviable. But subsequently it has trended downwards to 4.1% – just 0.1pps above pre-pandemic levels, and so near record lows.

One big risk, however, is a lost generation of workers – elevated structural unemployment among under-25s whose educations, career prospects and life outcomes have been blighted by school and university closures, bodged exam results and lost work experience opportunities.

In addition, while working from home might provide a long-term boost to productivity (though this is far from guaranteed). Trends in productivity need to be closely monitored. The Government’s tax and spending plans rest upon some pretty firm GDP forecasts, which in turn are linked to some extremely bullish productivity projections. If that predicted boost to productivity does not materialise, it will tank growth forecasts – and the Chancellor’s chances of cutting taxes to ease cost of living pressures.

The public sector finances have taken a hammering unprecedented in peacetime

The good news is that government borrowing (PSNB ex) in the first eight months of the 2021/22 financial year, at £147bn, was down by 47% on the same period in 2020/21.

The bad news is that that comes after the highest level of borrowing since the end of the Second World War – £322bn or 15% of GDP.

Around a quarter of public sector debt is index-linked to inflation. This is already adding to the costs of servicing the debt, spending on which was up by 200% year-on-year in December 2021, at £8.1bn. In order to quash inflation, the Bank of England (BoE) is now moving definitively in the direction of raising interest rates. But this is going to feed through into debt costs in another way. Whatever happens, the cost of servicing the national debt will only grow in 2022, to the detriment of other priorities. Rebalancing the books, meanwhile, is going to be a long, uncertain and exacting process.

.

Tax rises are set to squeeze businesses and households at the worst possible time

Two years of Covid spending has seen the size of the British state balloon. In an attempt to pay for all this the Government has resorted to a series of planned tax rises. First is the Health and Social Care Levy, which from April this year will add 1.25% to employers’ and employees’ National Insurance (NI). This levy is a tax on jobs and job creation coming at a time when employment patterns are in flux.

This is set to coincide with a 6.6% increase in the National Living Wage (from £8.91/hour to £9.50/hour), further increasing the burden on employers and distorting the labour market. Official forecasters expect higher unemployment as a result. The workers most likely to be impacted by this are young people working in sectors such as hospitality – i.e. those facing the greatest uncertainty in the post-Covid economy.

Businesses are also looking ahead to a corporation tax cliff edge in April 2023. The headline tax rate is due to rise from 19% to 25%, the super-deduction is scheduled to expire, and the Annual Investment Allowance is set to fall from £1 million to £200,000.

Indeed, due to the impact of Covid, the tax-to-GDP ratio is also on course to reach 36.2% within five years. The tax burden will then be at its weightiest since the heyday of state socialism in 1951, when Clement Attlee was Prime Minister and George VI sat the throne.

Britain is facing a cost of living crisis, with inflation on track to hit a 30-year high even as taxes are going up.

Inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 5.4% in the 12 months to December 2021, with prices having risen across a range of goods and services.

Debate continues over how transitory or persistent (or even structural) UK inflation will prove in this context. There is a pretty strong consensus that prices will continue to increase well into 2022.

So far British consumers have been protected from the worst of record natural gas wholesale prices due to the energy price cap, with a swathe of energy companies going bust instead. But when the cap is raised in April, annual energy bills for the average household will go up by £693. The IMF forecasts inflation will hit 5.5% in April, while the Bank of England and some independent forecasters project it to reach around 7%. April 2022 could thus see the highest level of inflation in the UK since March 1992, when it was at 7.1%.

Despite the talk of building a high-wage economy, relying on pay rises to offset rising prices and tax increases is unrealistic. Outside of a few specific sub-sectors such as HGV drivers, robust wage growth in 2021 mainly reflected statistical artefacts.

In fact, the latest ONS data points towards a firm decline in real wages in November 2021 – inflation stood at 5.1% whereas wage growth stood at 4.2%. The April ‘jobs tax’ is only going to put more pressure on worker’s pockets. Give that the clamour to mitigate cost of living pressures is only going to grow as 2022 progresses, the Government would do well to get ahead of the game.

So what is to be done?

Faced with the scale of these economic challenges, the worst thing would be a policy of drift: drift towards tax-and-spend, drift towards a big state, drift towards demand-side interventions to address supply-side problems.

The Government needs to prioritise economic growth – which helps with so many other problems – via supply-side reforms, lower taxes and business-friendly policies. It needs to ease the cost of living crisis by reducing the tax burden and preparing now for the deprivations of winter 2022/23. And it needs to square this with sound public finances via spending restraint and enhancing public sector productivity.

Against a dispiriting economic backdrop, it is more important than ever to make the case for markets, freedom, enterprise, opportunity and ownership as the pathways to prosperity. To quote F.A. Hayek: ‘If old truths are to retain their hold on men’s minds, they must be restated in the language and concepts of successive generations’.

This is an edited version of the Economic Bulletin from the Centre for Policy Studies. To read the full report click here.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.