It’s taken a while, but I think I’ve come up with a solution to the NHS funding crisis. Ready? Every time someone accuses the Tories of having a secret plan to “destroy” or “privatise” the NHS, they have to pay £5 towards its upkeep. Hell, even if we made it £1, we could probably fund a couple of decent-sized hospitals.

There is no doubt that the health service is in a desperate state. There have been warnings from parliamentarians of all parties, including former health secretaries and health ministers. And from various medical bodies, including the Patients Association, Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of GPs, Royal College of Nursing and many others. Even the Red Cross and OECD have chimed in.

But this crisis is not the result of callous Tory neglect, or even of inadequate funding (though money obviously plays a part). It is the result of decisions made not just over the last five years, but over the last 50.

It is the product of a system so laden with conflicting incentives, that has had so many reforms and restructurings bolted on to the frame, that it brings to mind that old joke about navigation. How can we fix the NHS? Well, I wouldn’t start from here.

To understand what’s gone wrong – or rather, to understand a small fraction of it – it’s best to think of a hospital as a conveyor belt.

The job of that conveyor belt is to take patients from the start of their journey – turning up at A&E, or via referral from their GP – to the end as quickly, humanely and cheaply as possible. Ideally, this will mean their returning home, hale and hearty. Sometimes, it will mean transfer to a care home – or a funeral home.

This may seem like a callous description, but it’s the only way the system can possibly work. With more patients coming in all the time, the conveyor belt needs to keep whirring them through the system in order to be able to cope.

This, in essence, was the thinking behind the four-hour target for A&E patients to be seen and treated. It was presented as a guarantee that no patient would suffer unduly. It was actually a brute-force way of making sure the conveyor belt kept going at high speed – of pushing patients through the system faster.

The basic reason the health system is in such trouble is that every single element of this conveyor belt is starting to break down.

At the front end, there are more and more patients coming in. In October (the last month for which we have figures) there were two million visits to A&E. That’s up by 300,000 on the equivalent month in 2011. A shift towards preventative care was meant to be keeping people out of hospital. Instead, they’re arriving in droves.

This influx is the result of many things. Partly, it’s a consequence of GPs no longer offering weekend and evening services – or only offering them extremely grudgingly. Partly, it’s the result of the four-hour target itself: once people had clocked that they were guaranteed relatively prompt treatment if they turned up at hospital, making a GP appointment for a few days’ (or weeks’) time turned into a mug’s game. And it’s also down to an unintended side-effect of the Lansley reforms, which ended up incentivising GPs to push patients up through the food chain by effectively giving them a volume discount.

But it’s also because of demographics. The population is becoming (shock news, this) larger and older. That means not just more patients, but more elderly patients – who tend to have more complicated (and more expensive) diseases.

This time last year, I wrote a special report for the Telegraph based on a week spent in one of the country’s best hospitals, the Queen Elizabeth in Birmingham, in the early weeks of the last winter crisis.

On the night I spent shadowing the staff in A&E – a hallucinatory blur of alarms and ambulance sirens and tireless effort from the doctors and nurses – the entire West Midlands health system essentially broke down. In the QEH, 28 patients ended up bedding down in A&E for the night. And of those, every single one was over the age of 75.

As one of the senior nurses told me, life in A&E isn’t the “sexy, Gucci stuff that you see on ‘Casualty’ on Saturday night” – it’s “patients just getting sicker, older and less able”.

What this means is not just that there are more patients going along the conveyor belt, but that there are more that need special attention – that force the machinery to work just that little bit harder to get them through.

The next problem is at the other end. Many of those elderly patients will not be able to go back home unassisted: they will need some sort of care package put in place, either in their own homes or in a care home of some kind. But the capacity isn’t there.

Due to a combination of government cuts – about which Ian Birrell wrote for CapX passionately and convincingly a few weeks back – and bureaucratic difficulties (social care is run by councils, not hospitals), patients often have to wait for weeks for the help they need.

And many patients, acting as good consumers, reject the options they’re given (or their families do on their behalf) while shopping around for a better product.

What this means is that hospital beds – whose nightly running costs are fantastically high – get filled with people who aren’t actually sick at all, or at least not acutely so. They’re just waiting for somewhere to go, either at their own insistence or because of SNAFUs down the line.

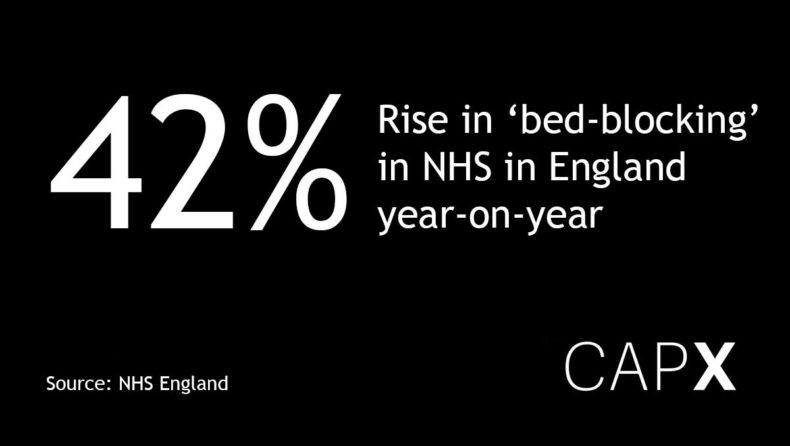

These “bed-blockers” not only cost the NHS billions – slowly, inexorably, they gum up the conveyor belt. New patients are arriving by the day. But there’s nowhere to put them. So, as happened in Birmingham on my visit, the entire system becomes logjammed.

This is why hospitals are converting every nook and cranny they can find into what are, effectively, care homes – improvised and in some tragic cases largely neglected wards on which these elderly patients can be parked so as to make room for new arrivals. It’s also why non-emergency operations – elective surgeries such as hip replacements – get pushed back and back and back, as all available resources are devoted to getting the belt moving again.

On top of all of this, there are the structural issues. That NHS conveyor belt is a rickety old thing – the subject of so many bodges and repairs and alterations over the years that no one is quite sure how the whole thing works, where nudging one part here results in another bit over there falling apart.

The Government is, of course, well aware of this. Under the last administration, No 10 convened regular high-level summits to discuss how A&E could be fixed. The conclusion? That it literally could not be. The system was so messed up, the politics so toxic, that no one – with the potential exception of Simon Stevens, the chief executive of NHS England – was in a position to drive through any significant changes without the risk of everything becoming even worse.

This does not mean that money is not important. Of course it is. Money is the fuel on which the NHS runs, and it will – as Stevens told MPs this week – need a lot more in the years to come.

But it is the structure of the conveyor belt that dictates how that money is spent – whether it is used to keep the wheels whirring efficiently or to shove a grinding and protesting system into life.

So if we really do want to fix the NHS, we need to think not just about its funding, but its structures – the incentives that shape the flow of patients along the conveyor belt.

The truth is that Labour critics of the Tories do have a smidgeon of a point. The NHS is not being “privatised”, and will not be so any time soon – in fact, the Blair government expanded private involvement on a far greater scale than the Conservatives have dared to.

But the NHS is still a creature of the market – or rather trapped in an ungainly compromise between market and monopoly. In order to make the conveyor belt work better, various ministers from both parties bolted on market elements – the idea that providers should be able to compete, that money should follow the patient, that patients should be able to choose the best provider.

But it has never followed through the logic of that – for example by letting good hospitals expand to cope with demands, even if it means allowing bad ones to close. “We need to have one system or the other,” Dame Julie Moore, the chief executive of QEH told me. “We’ve neither got a market, nor a managed system – it’s neither fish nor fowl. We say patients can choose, but the money doesn’t follow the patient.”

It is only fair to record that most NHS staff – for whom I have the most profound admiration and appreciation – are probably rather more sceptical towards the market aspect of its operations than I am. But we’ve tried running the NHS as a monopoly, and it didn’t work. And contrary to Labour spin, we haven’t actually tried running it as a market in the proper sense: a place where incentives and rewards correlate properly with performance.

Partly that’s because we are, when it comes to the NHS, bizarrely blinkered. We appear to feel that we are the only people in the world who have come across the idea of universal healthcare free at the point of delivery. That we are the only people who are committed to it. And that, somehow, the state has a god-given right (and duty) to provide that healthcare itself. But why should it matter who fixes your liver any more than it does who fixes your car, as long as they get the job done properly?

Ultimately, the NHS faces a problem of infinite demand and finite supply. One solution to this – the one from the old days – is for people to take what they were given by the producer interests, and lump it. Another is to try something new – to move towards a system in which there is proper diversity and competition, in which people can chip in towards topping up their care via insurance, and in which the tariff system is geared towards keeping patients healthy rather than paying per procedure they undergo.

This isn’t such a radical move. In fact, it’s describing what already exists. In countries across Europe – many of them hardly hothouses of neo-liberal orthodoxy – healthcare looks very different. While all systems differ, there is generally a blend of public and private provision; wide choice for patients in terms of who to be treated by; funding via social insurance; and extra payments via private insurance to top up care by those who can afford to pay. The ends are the same. But the means are far more effective.

It is near-impossible for any one human being to get their head around the scale of the NHS’s problems and peculiarities. Every time I think I have managed it, I have another conversation with a doctor or other health professional that sends me down a completely different rabbit hole of warped incentives and contorted bureaucracy. (Among other things, I haven’t even talked about the fact that we’ve got the wrong kinds of hospitals in the wrong places, or the looming crisis in medical manpower.)

But if the current crisis makes anything clear, it is that the patch jobs are no longer working: the conveyor belt is breaking down more and more often. It’s time we stopped treating this misshapen lump of a service as a beloved family pet, and started to get the wrenches out.