When a presidential candidate sells America an apocalyptic vision of a broken country that only he can fix, his victory doesn’t just represent a sharp political rupture. It also suggests that for at least some Americans, there is a great deal of truth in what he is saying.

Since Donald Trump’s rise, first to the Republican nomination and then to the White House, there have been a great many attempts to make sense of why his message appealed to the white working class.

Most, however, lack the rigour of a new study by a husband-and-wife team of Princeton economists, which suggests that the section of the electorate that carried Trump to victory last November isn’t just politically dissatisfied, but depressed and distressed in a way that is nakedly shocking.

‘Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century’, published last week by the Brookings Institute, is a harrowing piece of research by Anne Case and Nobel laureate Sir Angus Deaton.

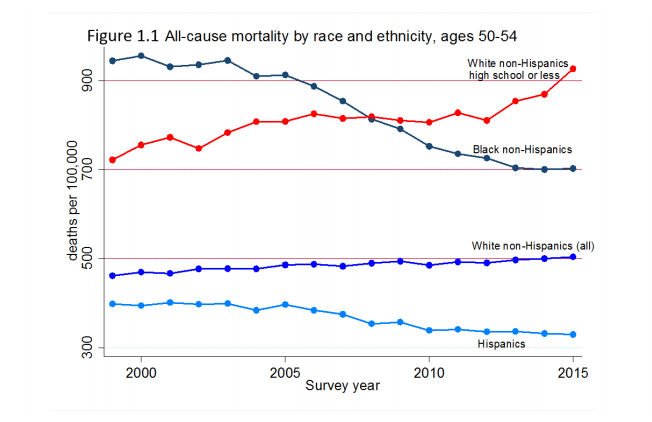

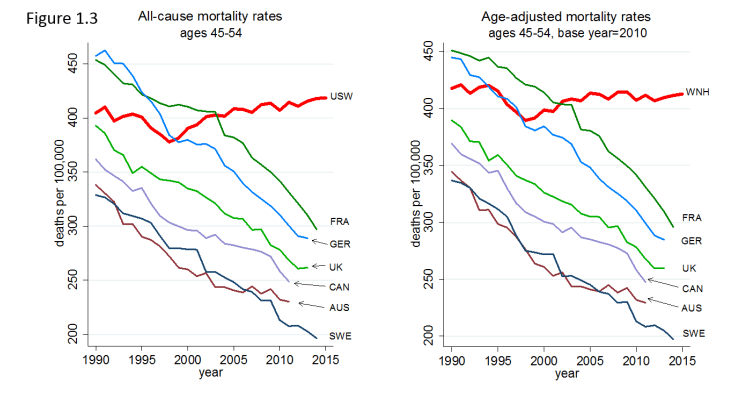

Their discovery, first reported in 2015, but this time laid out in detail, is that the middle-aged mortality rate, a figure that is plummeting across the developed world, is on the rise for white Americans. The number – a mark of economic and medical progress – fell consistently for more than a century, and continues to fall for black and Hispanic Americans. But has been on the rise for whites since 2000.

What’s going on? Among white Americans with a college degree, mortality rates are actually falling. But the number is rising sufficiently quickly among those with no education beyond high school to push the overall figure up.

Comparison with their black compatriots only underscores the scale of the problem in white America. In 1999, the mortality rate of whites without a high school degree was 30 per cent lower than blacks with the same level of education. By 2015, that relationship had reversed, with the white mortality rate 30 per cent higher than the figure for black Americans.

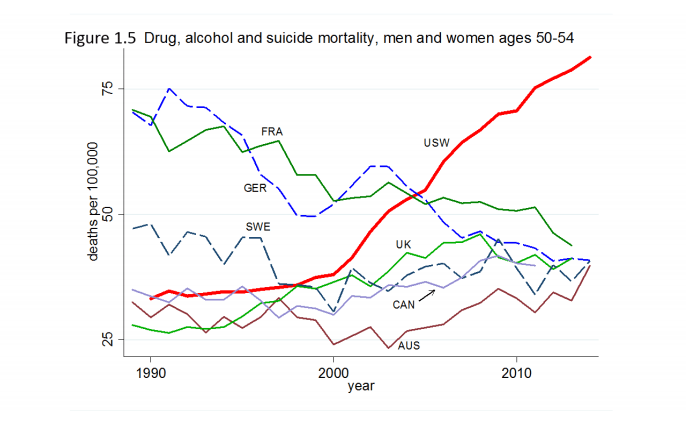

More troubling than the trend itself is what has caused it. You might imagine ailments of affluence — heart disease brought on by fat and sugar-rich diets and a sedentary lifestyle, say – were to blame, but the answer is more sinister. According to Case and Deaton, the upwards surge is the result of a spike in the number of “deaths of despair”, the term they use for suicides and drug and alcohol-related mortalities.

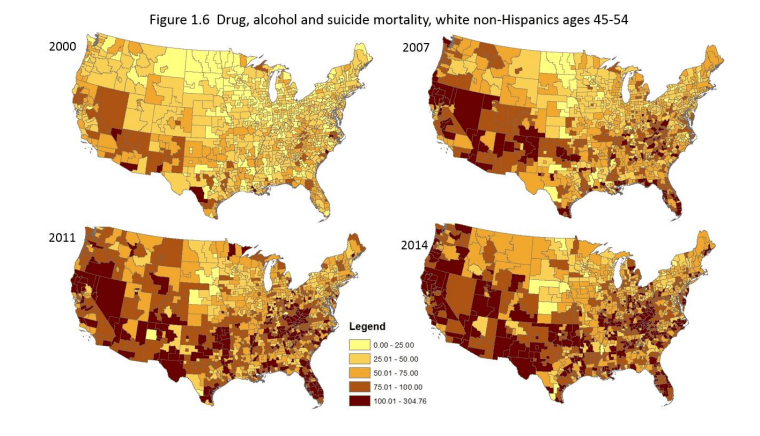

What began as a local problem has become a national problem. According to the report, the epidemic “spread from the south-west, where it was centred in 2000, first to Appalachia, Florida and the west coast by the mid-2000, and is now country-wide.” The increase occurred “at every level of residential urbanisation in the US; it is neither an urban nor a rural epidemic, rather both.”

Given their impeccable academic credentials, Case and Deaton’s findings will inevitably become supporting evidence for all manner of competing and contradictory theories. Which is presumably why they devote part of their paper to pointing out which of the more predictable theories are not supported by their evidence.

For instance, they dismiss a caricatured argument that many on the Left have made, in which wage stagnation and growing inequality have driven Americans to drink and drugs. The glaring problem with the “inequality kills” theory, which counts Joseph Stiglitz as its foremost proponent, is that it doesn’t account for the whiteness of the problem. As Case and Deaton point out, black household incomes performed in line with white household incomes between 1990 and 2015, yet black mortality rates have fallen steadily.

Nor does it account for the Americanness of the problem. Stagnant wages and growing inequality in comparable European countries have not triggered a rise in mortality rates.

“Taking all the evidence together,” they write, “we find it hard to sustain the income-based explanation.”

That is not to say that economics, and the labour market in particular, aren’t an important part of why so many middle-aged white Americans are dying. Case and Deaton’s tentative explanation is “a long-term process of decline, or of cumulative deprivation, rooted in the steady deterioration in job opportunities for people with low education”.

But non-economic changes in society are also part of the story. “Cumulative disadvantage,” they conclude, “in the labour market, in marriage and child outcomes, and in health, is triggered by progressively worsening labour market opportunities at the time of entry for whites with low education.”

Case and Deaton are describing what, to those on the losing end, looks like the downside of greater choice: social and economic change has “left people with less structure when they… choose their careers, their religion and the nature of their family lives. When such choices succeed, they are liberating; when they fail, the individual can only hold him or herself responsible.”

Added to this tinderbox of insecurity are loosely prescribed painkillers, which have triggered an opioid epidemic across the country. Since 1999 the number of prescription opioids (drugs like oxycodone and methadone) sold in the US has nearly quadrupled and the number of deaths from overdoses of those drugs has more than quadrupled.

How to fix the mess? Case and Deaton point out some low-hanging fruit. Rethinking the regulation of highly addictive painkillers would be a good start. But given that the causes of white America’s mortality problem are a tangled ball of long-standing economic and social problems, there are very few obvious solutions.

Because these problems are mutually reinforcing, even policies that “successfully improve earnings and jobs, or redistribute income” will take years to reverse the trend. No matter how many quick fixes the President promises, the white working class’s problems are going nowhere.