Mother’s Day is a celebration of motherhood and mothers within each family. As the US marks the day, it also seems appropriate to celebrate the improvements in the lives of mothers, who have benefited from the spread of better medical technology, information about best practices and general economic development. Perhaps nowhere is that progress more evident than when it comes to improvements in maternal health. These five charts demonstrate the global progress in the area of maternal health over the last few decades:

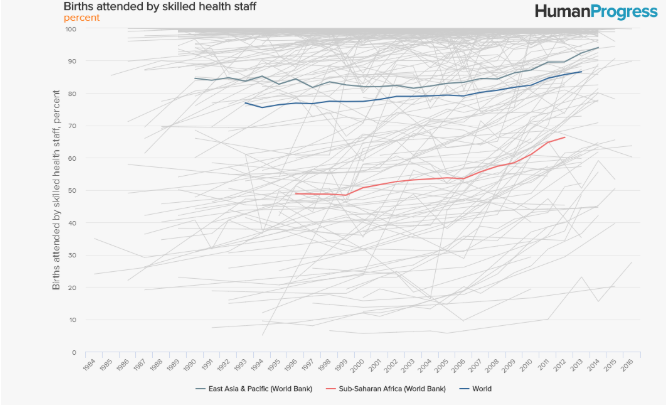

1.The maternal mortality rate is falling

First of all, women are more likely to survive pregnancy and birth to enjoy the status of a mother in the first place. “Maternal mortality” refers to death of the mother during either pregnancy or childbirth. According to data from the World Bank, in 1990, the global maternal mortality rate stood at 340 per 100,000 live births. By 2015 that figure had fallen to 169. That represents a decline of over 50 per cent.

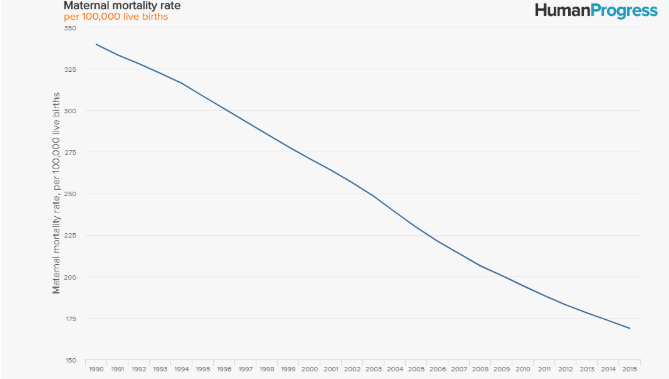

2. The total number of maternal deaths is also falling

The decrease in the rate of maternal mortality has been so dramatic that the total number of such deaths has also fallen. Between 2008 and 2015, the total number of yearly maternal deaths declined by 47,535, despite a global population increase of over 593 million people over the same time period. With so many more people in the world, it would be possible for the rate of maternal deaths to decline even as the total number of such deaths did not. But happily, the total number of deaths in childbirth has also come down.

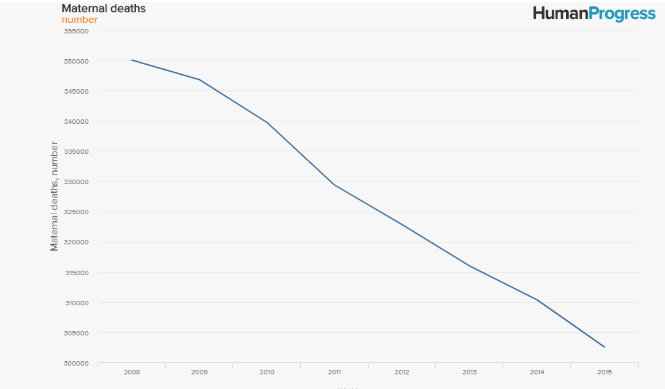

3. Maternal complications are becoming rarer

Not only are mothers less likely to die during childbirth than in the past, but thanks to better medical care they are also less likely to suffer any maternal complications, fatal or otherwise, according to data from the University of Washington’s Global Health Data Exchange. Maternal disorders are defined as those complications occurring during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. These include ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and abortion (all of which have become less deadly for the mother); obstructed labour and uterine rupture (also less deadly); maternal haemorrhage, including placental disorders (less deadly once again); maternal sepsis and other maternal infections (less deadly as well); hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (ditto); and eclampsia. From 1990 to 2017, the prevalence of maternal disorders per 100,000 people fell from 177.25 to 124.55. That’s a decline of 30 per cent.

4. More pregnant women receive prenatal care

Part of the reason why pregnancies involve fewer complications than in the past, and are less likely to conclude with the mother’s death, is that pregnant women around the world are more likely to receive prenatal care than in the past. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, the world’s poorest region, a majority of pregnant women now receive prenatal care. That region’s share of pregnant women receiving prenatal care increased from 74.7 in the year 2000 to 85.5 in the year 2013. When one considers how much sub-Saharan Africa’s population has grown during that time—by over 280million people—it becomes especially clear that the number of additional women receiving prenatal care is significant.

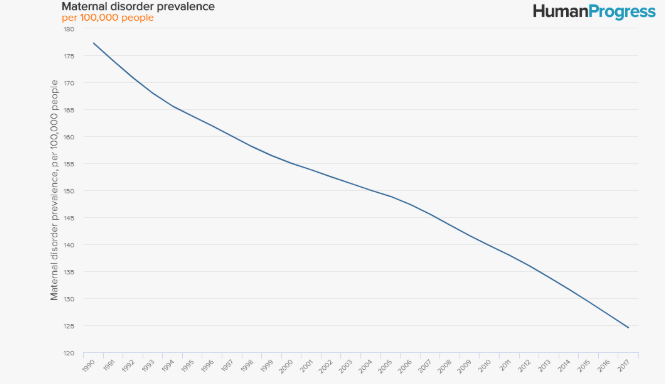

5. More births are attended by skilled health staff

While wide disparities remain between the rich and poor countries, the share of births attended by skilled health staff has also improved. The World Bank defines skilled health staff as “personnel trained to give the necessary supervision, care, and advice to women during pregnancy, labor, and the postpartum period; to conduct deliveries on their own; and to care for newborns”. Assistance by such trained professionals during birth reduces the incidence of maternal and newborn deaths. So, a rising share of births attended by skilled health staff is an indicator of progress. In East Asia and the Pacific, the share of births attended by skilled health staff rose from less than 85 per cent to over 94 per cent from 1990 to 2014. In poorer sub-Saharan Africa, the share of births attended by skilled health staff grew from only 49 per cent—less than half of all births—in 1996, to over 66 per cent in 2012.