The third and fourth parts of our Battle of Ideas series consider an issue that has quietly been moving up the political agenda – housing. As I’ve argued previously, the 2017 “youthquake” was in fact a rentquake, and the difficulties facing younger would-be homeowners are of far greater political significance than is commonly acknowledged.

For example, at the last general election, the entirety of swing between the two main parties, and very nearly the entirety of the increase in turnout, was accounted for by renters, according to data from the British Election Study.

More recently, the December Ipsos MORI issues index put housing as voters’ third most important issue facing the UK, behind only Brexit and the NHS.

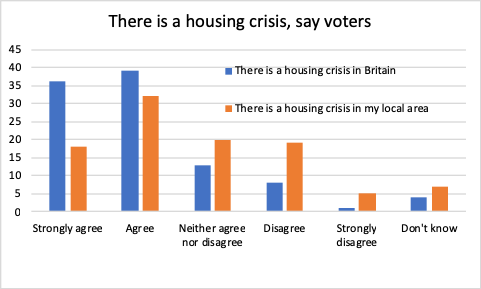

As ever, we wanted to drill a bit deeper into opinion on housing, both nationally and locally, and people’s motivations. Firstly, can the current housing situation reasonably be described as a crisis? We asked how much respondents agreed or disagreed with statements that there is a housing crisis “in Britain” and “in my local area”.

On the first question, opinion was overwhelmingly in agreement, with three-in-four answering “strongly agree” or “agree” that there is a crisis nationally. Eight per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed and 17 per cent answered neither or didn’t know.

As might be expected with such an emphatic result, there is relatively little variation – a clear majority of every group of voters agreed that there is a housing crisis. But there were some differences, with higher agreement among Labour voters (83 per cent) compared with Conservatives (73 per cent), among renters (81 per cent) compared with homeowners (72 per cent), and among Londoners (83 per cent) compared with all other regions.

On the second statement regarding respondents’ local areas, opinion was more balanced, but still two-to-one in agreement (50 per cent) over disagreement (24 per cent). The distribution between different subgroups had much the same pattern as the first statement, but at lower levels of agreement and higher levels of disagreement. However there was also a noticeable age gap, with over-65s (36 per cent) less likely to agree than others and, probably not coincidentally, a bigger party gap too.

Interestingly, people everywhere were likelier to think that the crisis was worse nationally than locally, which could be due to perceptions, or some sort of collective cognitive dissonance.

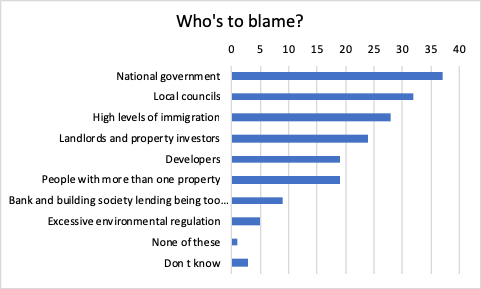

There is, then, a consensus that a crisis exists, although only a plurality rather than a majority think that one exists in their local area. So who or what is responsible? To those who had agreed that there was a crisis, we asked who was most to blame, with respondents able to pick up to three from a list of options.

The most popular response was national government, selected by 37 per cent, ahead of local councils on 32 per cent, although there was a big party difference. Tories were equally likely to blame councils as Westminster, while Labour voters were 13 points likelier to blame national government.

Among those who thought there was a housing crisis as a whole, “high levels of immigration” (28 per cent) came third, but among Leavers it came top. Yet this is not exclusively the view of Brexiteers by a long way – about a third of those citing immigration who voted in 2016, backed Remain.

Landlords and property investors (24 per cent), developers (19 per cent) and people with more than one property (also 19 per cent) came next. These responses saw relatively little variation between subgroups.

“Bank and building society lending being too strict” (9 per cent) and “excessive environmental regulation” (5 per cent) were the least-chosen responses.

While there are differences along party lines over which level of government shoulders most of the responsibility for the crisis, most voters blame at least one set of elected representatives. Since there is relatively little overlap between those choosing the two top responses (eighteen per cent selected both of them), the numbers above conceal the fact that half (51 per cent) selected at least one of them.

This helps to explain the electoral impact of housing. While various debates can be had about what the right policies are, will be, or would have been, as far as the voters are concerned – as with so many things – the buck stops with the politicians. And it’s those in office at the time the voters snap that pay the price, whether that’s fair or not.

We’ll return to housing theme next week. To be continued.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.