Every Friday, the pollster Populus send out a weekly round-up, which includes a section on the Top 10 most noticed news stories. It is a useful reality check on what has penetrated the public consciousness. Last week, for example, 54 per cent of people clocked Hurricane Irma, but only one per cent mentioned the announcement that the public sector pay freeze would be coming to an end.

When Emmanuel Macron was elected as France’s new President back in May, it registered with 5 percent of people in the UK, despite the wall-to-wall coverage in the months running up to the vote about the threat of a Marine Le Pen National Front administration.

I’m looking forward to reading next Friday’s email, to find out if Angela Merkel’s re-election for a fourth consecutive term hits the public radar. I very much doubt it will. And this is in no small part because, unlike in France with Le Pen, or the Netherlands with Geert Wilders, or the United States with Donald Trump, there isn’t an insurgent candidate in Germany, or a “populist threat”.

So why has Germany resisted the populist revolt? And what do we mean by populism? These are questions which I attempted to answer with Claudia Chwalisz in our new report for the Legatum Institute, “A brief guide to the German election: Merkel’s coalition crossroads”.

There is a mounting academic consensus that populism is a form of rhetoric which claims that legitimate authority flows from “the people” (“us”) rather than the establishment elite (“them”). It is not, in itself, an ideology such as liberalism, socialism or communism. Rather it is a strategy used by politicians of all political stripes and is largely void of concrete public policy prescriptions about the economy, foreign policy or welfare. Hence in the recent French election, Le Pen on the far right, Jean-Luc Mélenchon on the far left and Macron in the centre, all displaying populist tendencies.

The unifying thread between all populists is the moral claim of democratic legitimacy and the proposal of democratic or constitutional reforms to give more power to “the people”. In Germany, Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Left Party are both considered as populist parties. Both have some support, mostly in regional pockets of the country, but neither party looks likely to win more than ten per cent of the votes on Sunday.

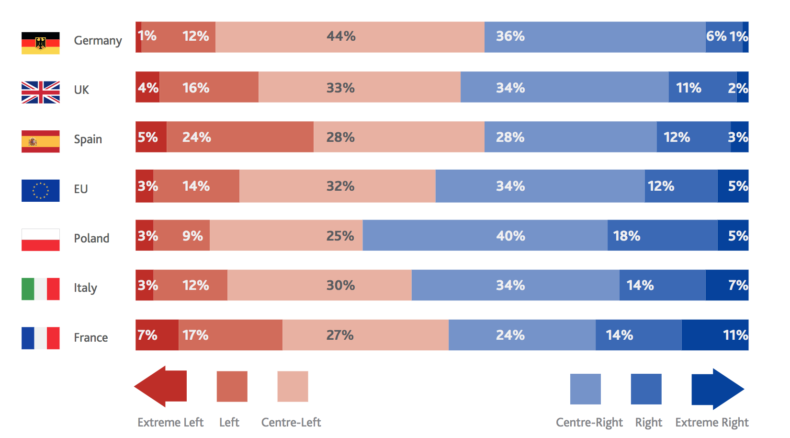

Compared to all other EU countries, Germany has the smallest proportion of people that identify on either the extreme Right or Left (2 per cent in total) and the highest proportion of centrists (80 per cent).

While it may be obvious, no analysis about populism in Germany would be complete without mentioning its history of Nazism, on the one hand, and communism on the other. In terms of the far Right, no party has made significant gains since the 1940s until the AfD. It was polling much higher (around 15-20 per cent) at the height of the refugee crisis and throughout 2016, but it has fallen back to around eight to ten per cent support in the polls as election day approaches.

There are a few reasons for this decline. One is that Merkel’s tightened stance on immigration and refugee policies took some of the wind from AfD’s sails in 2017. Another is that, like many other far right parties across Europe, the AfD has also been prone to infighting between the moderate and extreme wings.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the Left Party occupies the far left populist space. They rode a wave of popularity in the mid- to late-2000s, following Gerhard Schröder’s economic reforms, which turned parts of the SPD and trade unions against the centre-left. With a charismatic leader at the time, Oskar Lafontaine, who had resigned from the Schröder government to become one of the SPD’s greatest critics, he managed to bring together many factions to form one Left Party.

But with an ultimate aim of overthrowing capitalism, a rigid anti-Nato position and no room for compromise, it has been isolated by the centre-left Social Democrats and the Greens who have for many years ruled out forming a coalition with them. This has limited The Left’s support.

In my work on populism for the Legatum Institute, I have identified three key drivers: economic, social and political. Unlike in the Netherlands and France, none of the three has provided fertile terrain for a populist uprising in Germany.

In terms of most economic metrics, the German economy has fared incredibly well during Merkel’s 12 years as Chancellor. GDP has been increasing; there are a record number of people in employment; youth unemployment and long-term unemployment have both fallen; and in 2015, the budget was balanced for the first time in over 40 years.

German voters are acutely aware of their good fortune. ARD and Infratest Dimap polling shows that since Merkel took office, the proportion of voters who think that Germany’s economic situation is good or very good has increased from 15 per cent in 2005 to 81 per cent in 2017. And the Chancellor is rewarded accordingly in the polls.

Beyond the economy, social factors also play a role in explaining support for populist politics. Looking at German attitudes to globalisation and immigration provides an additional explanation why support for the AfD and The Left is currently limited. A recent Kantar Public and Infratest Dimap study comparing attitudes in Germany, the Netherlands, France and the UK highlights how Germany stands apart from its European neighbours in this regard.

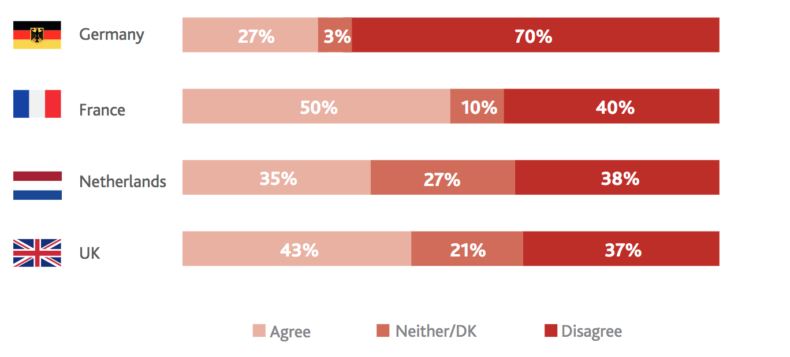

The vast majority of those surveyed in Germany (82 per cent) see globalisation as an opportunity for their economy, compared to only around half in the other three countries. Equally, those in Germany are much less likely to think that globalisation threatens their identity—only 27 per cent agree, compared to 50 per cent in France, 43 per cent in the UK and 35 per cent in the Netherlands.

In addition to economic and cultural factors, political disaffection is the third ingredient in the populist cocktail. Once again, Germans currently differ from their other European counterparts in being more satisfied with the state of their democracy and their political elites. According to a Kantar Public and Infratest Dimap study from June 2017 on democracy and populism, a majority (64 per cent) of people in Germany are satisfied with the way democracy works.

Even more striking is the disparity in views about political actors: less than three in 10 people in Germany agree that elites have been failing over the past 20 years, with 65 per cent actively disagreeing with this statement. By contrast, the vast majority in France (81 per cent) and the UK (57 per cent) agree.

That said, populism is not dead in Germany. There is even a possibility that the AfD might come in third which, in the event of a continuation of the current “Grand Coalition”, would make them the official opposition. This is not a change election. German voters are content with Mutti. So populism has been kept at bay, for now.