Civil unrest in Venezuela has dominated headlines over the last few weeks. The Venezuelan people are protesting against the continued autocratic rule of President Nicolas Maduro. Following his sham re-election last May, during which he prevented leading opposition parties from fairly competing, most Western governments have refused to recognise Maduro’s legitimacy. But as Maduro ignores these protests and begins his second 6-year term, the pressure for him to step down is growing by the day.

One thing is indisputable: these protests clearly show that Venezuelans are desperate for political and economic change.

In early 2001, former President Hugo Chavez first started to chip away at his citizens property rights by issuing a decree for the expropriation of private Venezuelan farmland. “To those who own the land, this land is not yours. The land is not private, but property of the nation,” Chavez proudly announced. By 2005, hundreds of private companies, shops, and agricultural supply firms also fell victim to Chavez’s runaway nationalisation.

What was the result of Chavez and Maduro’s socialist experiment? What had been the richest economy in Latin America now faces an annual inflation rate of 80,000 per cent and GDP per capita is now half of what it was in 2012. Mass food shortages have meant that the average Venezuelan has lost 11.4kgs, but unsurprisingly Maduro’s waistline continues to expand.

It seems Chavez’s claim that “the only way to save the world is through socialism,” was, unsurprisingly, incorrect.

Some organisations and individuals, from Oxfam to Jeremy Corbyn, once admired Venezuela’s socialist experiment. Today, they are curiously silent about Venezuela’s decline. For the rest for the world, the now-impoverished nation offers a clear reminder of the necessity of property rights for any functioning economy.

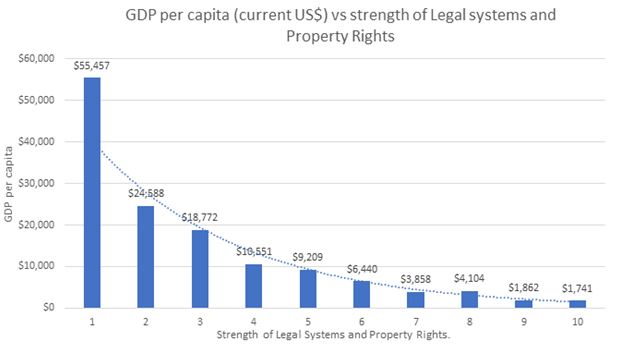

Using data from the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World report, I have split the 162 countries that the report analysed in 2016 into deciles (i.e. each decile represents 10 percent of the countries measured) based on the strength of their property rights. I then correlated these deciles with their average gross domestic product (GDP).

The results are staggering.

*GDP data taken from WorldBank using 2016, the most recent year the Fraser Institute has data.

The countries in the decile with the strongest property rights have an average income of over $55,457. That figure is 125 per cent higher than those nations in the second most property-friendly decile. Similarly, the countries with the strongest property rights have an annual income 31.8 times higher than those nations with the weakest property rights.

The countries with the strongest property rights, in descending order, are Finland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, Luxembourg, Singapore, the Netherlands, and Denmark. Unsurprisingly, Venezuela is in the decile with the weakest property rights, ranking in the second to last position — just above the Central African Republic.

Interestingly, of the four other aspects of economic freedom that the report covers — size of government, sound money, freedom to trade internationally, and regulation — it is property rights that has the strongest correlation with economic prosperity.

One reason property rights remain crucial to economic growth is that without the former, people lack the incentive to invest, innovate, or produce. As the 17th century economist Adam Smith famously wrote, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” And in Venezuela, where workers have little self-interest in the production process, shortages of basic goods and foodstuffs are commonplace.

However, some hope remains for Venezuela. The United States, Canada and more than a dozen Latin America countries, have recognised the leader of the opposition, Juan Guaido as acting president. The UK, Germany, France, and Spain have also said they will support Guaido, if Maduro does not hold fair elections by February 2.

A new leader who will protect property rights offers Venezuela a chance to reverse the past 20 years catastrophic land seizure policies. But if Maduro refuses to step aside and continues on his socialist course, life for Venezuelan citizens will likely get yet more nightmarish.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.