Imagine you run a company. There you are, quite literally minding your own business. When suddenly, a man from the Government appears on your doorstep. Your industry is full of bad people, he says, who have done bad things. So pay up, right now. Or he’ll shut down your firm.

That doesn’t really sound like 21st century Britain, does it? More like Putin’s Russia or Erdogan’s Turkey. But that is what is happening to the housing sector.

In the wake of the awful fire that consumed Grenfell Tower, we have all become uncomfortably aware that many high-rise buildings were insulated with material that turned out to be extraordinarily flammable. This needs to be fixed. Doing so is vastly expensive.

The solution reached by Michael Gove has, essentially, been to strong-arm Britain’s housebuilders. The Government has imposed a new 4% Corporation Tax surcharge on the sector, set to raise £250m a year over 10 years. It has introduced a Building Safety Levy, which is intended to raise another £3bn. And now it is requiring them to make a massive one-off payment of a further £2.5bn to fix the cladding on properties they themselves built, even though they followed all the rules in place at the time.

This may seem like it’s only fair – someone has to pay, after all, so why not the people who built the buildings? But it isn’t quite that simple. Many of the cladded properties were built by foreign companies, who so far aren’t paying a penny. Nor are the firms that actually made and installed the cladding – including the cladding on Grenfell Tower itself. Firms are also being asked to fix 30 years’ worth of buildings, potentially paying 100% of the costs even if they originally only owned part of the building. On top of which, Gove himself admitted to The Sunday Times that ‘faulty and ambiguous’ government guidance was partly to blame.

Most startling, however, are Gove’s tactics for rustling up the cash, which the Treasury has ensured his own department is on the hook for if it can’t extort it from the industry.

Builders have been told that they need to sign the deal presented by the Government by March 13, or they won’t be allowed to build. Any relevant developers who do not promise to pay compensation for the (perfectly legal) properties they built will not be included on the Government’s new list of ‘responsible actors’, and will therefore be blocked ‘from commencing developments for which they have planning permission, and from receiving building control approval for construction that is underway’. This is, quite literally, a case of demanding money with menaces.

It is important to stress how unusual and alarming this is. It is not just that British firms are being disadvantaged compared to their foreign rivals. A core principle of taxation in free societies is that it should be neither retrospective nor arbitrary: the Government can impose extra costs on you going forward, but it should not punish you for doing perfectly legal things that it has since decided were wrong. And it should certainly not resort to blackmail.

Now, the housebuilders are not a group that inspire natural sympathy. Many of them are very large companies that tend to make very large profits. And those profits were juiced over the last decade by the government-backed Help to Buy scheme. I’ve heard even some free market-minded people observe that the Government is just taking away what it’s already given.

But one of the basic principles of economics is that if you tax something more, you get less of it. And boy, have we been applying that to the housing sector. Including the cladding levies, industry body the Home Builders Federation estimates that builders have recently been subjected to additional taxes and regulatory requirements costing roughly £4.5bn a year – or, to put it another way, adding roughly £20,000 to the cost of the average plot. That’s without counting the wider increase in Corporation Tax that’s set to kick in come April.

Nor is the industry in the kind of shape to shrug off such costs. Housebuilding figures are still relatively healthy, but they are expected to fall sharply as the combination of higher interest rates and fewer planning permissions sends the market into the deep freeze. Then there are measures such as nutrient neutrality, the gloriously stupid policy under which the Natural England quango used a European legal ruling to halt housebuilding across swathes of the nation – resulting in a six-figure number of properties being cast into limbo.

Axing this idiotic rule would be the clearest possible benefit of Brexit, yet the Government seems paralysed. Then there is the series of concessions made to Theresa Villiers and her merry band (see articles passim ad nauseam) which will make it, yes, much harder to build. And as I pointed out last week, Villiers still isn’t satisfied with having blocked building on green belt and green fields – now she’s coming back for brownfield building, too.

I appreciate that I write an awful lot about housing. That’s not just because my mum has put some land forward for development. It’s because it really matters – just read this essay on ‘The Housing Theory of Everything’, the only flaw in which is that I was planning to write the same article a few weeks later.

The reason to highlight the cladding issue, and all of the other issues above, is that they mean that every single aspect of the housing market, every single factor that dictates how many houses are built, is now moving in the wrong direction. Interest rates are going up. Market sentiment is souring. The tax burden on the housebuilders is increasing. Planning legislation is getting stricter. The planning rules are getting more and more complex and burdensome.

Each of these, on their own, would nudge housebuilding in the wrong direction. Taken together, they are positively shoving it. And neither party seems to care. The Tories are hostage to the Villiers tendency. And Keir Starmer couldn’t even be bothered to mention the word ‘housing’ yesterday when outlining what he sees as the country’s biggest problems.

For some people, especially those Nimby activists who festoon my Twitter feed, the fact that Britain isn’t building might be a cause for celebration. But this week also saw yet another reminder of why it matters.

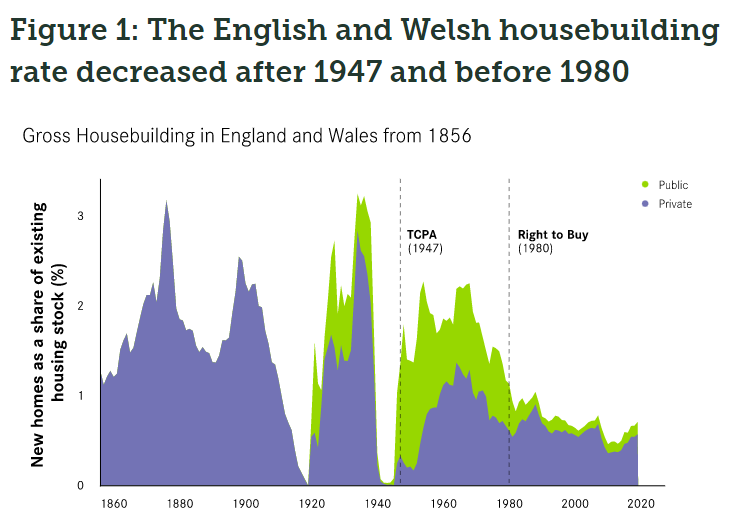

Earlier this year, the Centre for Policy Studies (the think tank I run, which also operates CapX) published a paper called ‘The Case for Housebuilding’. It showed, among many other things, that housebuilding in the UK has collapsed in recent decades. Between 1960 and 1990, we built 7.5 million homes. Between 1990 and 2020, we built 3.3 million. That disparity becomes even worse when you consider how much more quickly the population grew in that second period, and how small many of the newer homes are.

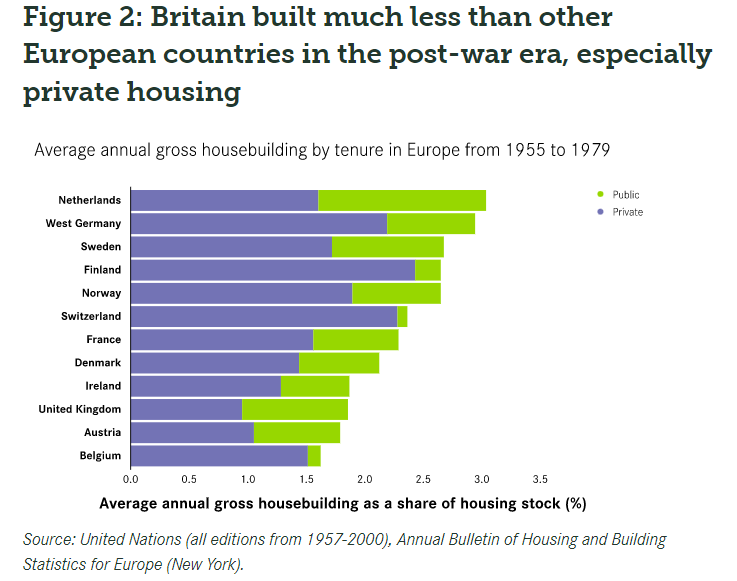

But a new report by Samuel Watling and Anthony Breach of the Centre for Cities – hardly a hotbed of pustulating right-wingery – argues that this picture is even worse than it looks. Because, it says, that earlier period was emphatically not one of high housebuilding once you compare post-war with pre-war, or the UK with the rest of Europe. In other words, the sharp fall outlined in our paper was from a starting point that was already inadequate. These are the key charts from their report, which make the point very clearly.

.

.

Their conclusion is not just that the idea that Britain’s housing problems all started when Maggie sold the council housing is an utter myth (though it absolutely is), but that the 300,000 homes a year target set by the Government, and enshrined in the 2019 manifesto, should in fact be far higher. Getting our level of housing stock up to the European average would involve building many more houses – perhaps as many as double that 300,000 a year target. Instead, we are set to fall far, far below it.

In 1955, a Tory re-election poster (which is still on sale on the party’s website) bore the striking slogan: ‘Shout it from a million new housetops – vote Conservative!’ If Watling and Breach are right, that might not have been quite as much of an achievement as it seemed. But it’s still a damn sight better than where we are now.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.