Another week, another blow to Ed Miliband. Yesterday the plug was pulled on a huge offshore windfarm, Hornsea 4, that could have powered more than two million homes. The owner Ørsted, the Danish state-owned company (and inspiration for Ed’s pet project GB Energy), announced it was ‘discontinuing the project in its current form’, incurring £400-500m in break costs. But while newsworthy in itself, the implications for the Government’s 2030 Clean Power goal are the real story – and the risk that a policy that was initially sold as a way to reduce bills could end up doing the opposite.

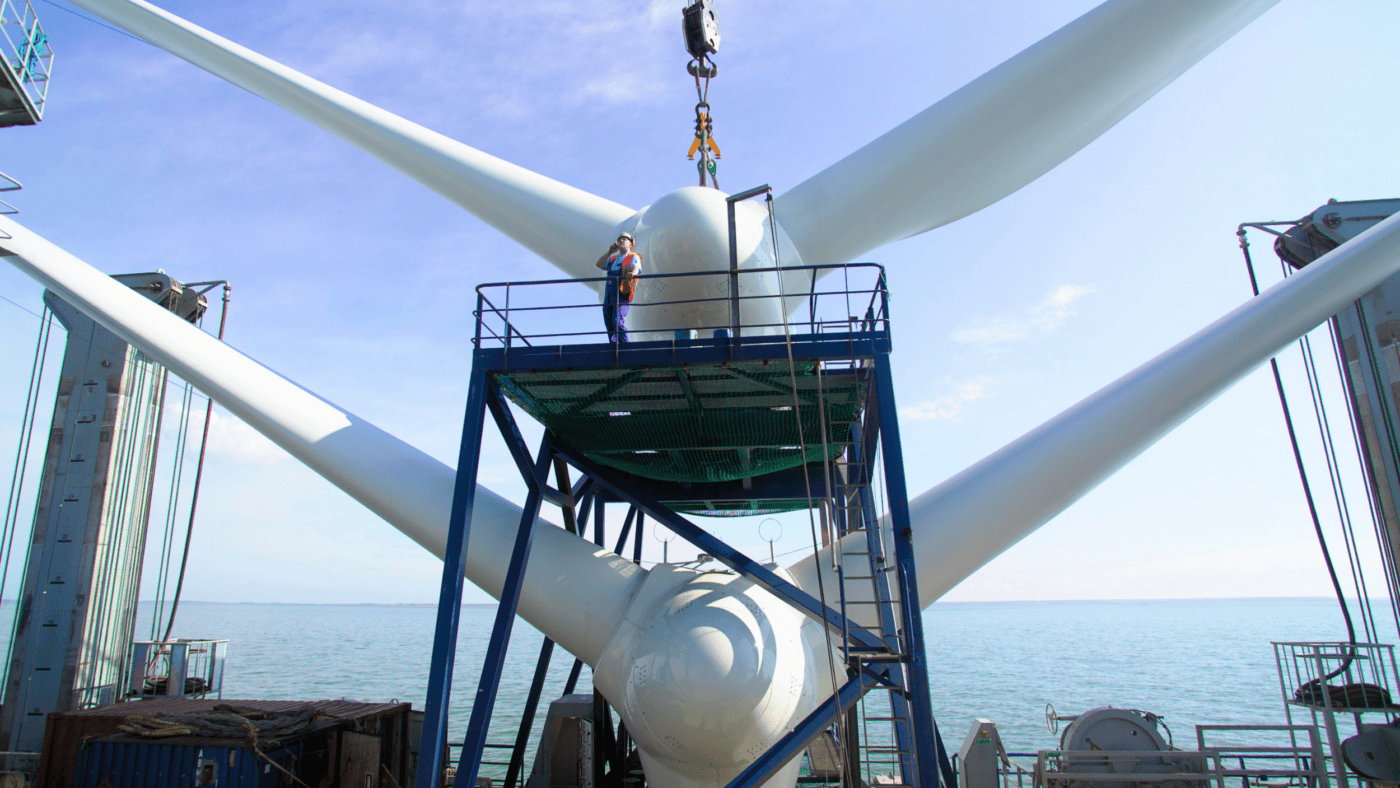

Offshore wind is meant to be the backbone of our future system, providing by far the largest chunk of our power by 2030 in the Government’s plans. But to make that happen requires us to build wind farms like there’s no tomorrow, going from 15 GW in 2023 to 43-50 GW in 2030. And yet the sector has had a rocky few years – supply chain pressures and increased financing costs post-Covid meant that 2023 saw big projects around the world delayed or halted.

That year’s CfD auction round was a notorious flop for offshore wind, failing to secure any new projects at the prices on offer. Last year, the sector seemed to get on firmer footing, and offshore wind returned to the auction, albeit at higher prices than before. And the biggest successful bidder was a flagship 2.4GW offshore project, Hornsea 4 – the very one that has now been cancelled.

In announcing the decision, Ørsted cited ‘continued increase of supply chain costs, higher interest rates, and an increase in the risk to construct and operate Hornsea 4 on the planned timeline for a project of this scale.’ This is a depressingly familiar story for the sector – we are building a huge amount of new renewable capacity (notoriously capital intensive) at a time of high interest rates and when many other countries are trying to do the same thing. Ørsted itself has been trying to claw its way back from a tough few years which saw its share price drop 80% and the appointment of a new CEO in January. (And of course in addition to these global factors, the company has had to contend with Donald Trump’s hatred of ‘windmills’ in its US business).

The fate of Hornsea could thus bode ill for this year’s auction round and the ‘strike prices’ consumers will end up paying for their power. RenewableUK, the trade body, warned yesterday that the Government must ‘ensure auction parameters reflect the cost increases we’re seeing in the supply chain and inflationary pressures’. And of course there’s the uncertainty on locational pricing hanging over the sector.

If strike prices do rise again this year, it will not only be bad news for consumers. It would also further undermine Ed Miliband’s claim that dashing to 2030 will lead to lower bills – in a recent report, the National Energy System Operator (NESO) warned of this directly as a potential downside: ‘There are also risks that the accelerated pace reduces competitive pressure, increases supply chain tightness or otherwise increases costs.’

And interestingly, Ørsted itself isn’t fully giving up the project – the press release quotes the CEO saying ‘we’ll seek to develop the project later in a way that is more value-creating for us and our shareholders’. Meanwhile the Department pledged to ‘work with Ørsted to get Hornsea 4 back on track’.

Ed Miliband desperately needs all of the offshore wind capacity he can get to hit the 2030 decarbonisation target. NESO mentioned in its report of last November that delivering Clean Power would require ‘almost the entire pipeline’ of capacity to come through the CfD auctions. In other words, 2030 is only five years away and given the time it takes to get such huge projects up and running, the Government can’t afford to be particularly choosy in terms of which projects it wants to support.

Which means large single projects like Hornsea 4 know they have significant leverage – and that’s bad news for a competitively priced auction. Indeed, in a further sign of the times, earlier this week the Government announced that this year’s round would no longer have a fixed budget – rather the Government will seek to buy a certain amount of capacity, and later work out how much it costs.

So one imagines the most likely result of yesterday’s announcement is that the project will re-bid into a future auction, but at a higher price – which means consumers will be paying more for exactly the same capacity. (Auction rules enforce a penalty period before they can re-bid – but Miliband told reporters yesterday ‘we are still committed to working with Orsted to seek to make Hornsea 4 happen by 2030’). Of course, the Government does have some flexibility in the exact capacity mix for 2030, but telling Hornsea 4 to take a hike would leave it with yet fewer options to hit the target.

And therein lies the folly of 2030, which Miliband himself has referred to as a ‘sprint’. Beyond the various contortions required to get there (in grid connections, for example) and the dodgy modelling underpinning the supposed cost savings, by so publicly tying itself to a (very stretching) goal, the Government has painted itself into a corner. Continuing supply chain pressures driving up costs for renewables? Sorry, we’ve got a target to hit. Individual large projects knowing they have you over a barrel and making brutal use of that fact to rinse billpayers for more money? It’s a manifesto commitment!

Now to be clear, decarbonising the power sector and building new renewable capacity is still of vital importance, not least to meet the rising demand from heat and transport that will come onstream in the next decade. But committing to do so at any price to meet an arbitrary political deadline is a recipe for a contorted system, rent seeking and potentially higher bills for consumers – quite the opposite of what was sold to voters at the election.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.