Planning is back in the headlines. The row du jour is over the housing amendments put forward by Theresa Villiers, which as I warned in The Sunday Times – and others have highlighted here on CapX – would slash housebuilding by effectively making it voluntary for councils, rather than compulsory.

In that Sunday Times piece, I described the amendments as ‘wicked, selfish and short-sighted’. That upset some of the proposals’ supporters, who also objected to my calling them ‘Nimbys’.

The Isle of Wight’s Bob Seely took particular issue with my claim that abolishing targets would slash housebuilding – something the Home Builders Federation and Lichfields estimate could cause a £17bn hit to the economy. Bob told GB News yesterday that my facts were ‘plucked out from the air’ and ‘absolute nonsense’.

On Times Red Box earlier this week, Bob had already tried to rebut charges that he was a Nimby, while also arguing that Nimbyism as conventionally defined is nothing to be afraid of – indeed, that his own definition of Nimby is ‘someone who is a local patriot’. I’m glad he did. Not only do I like Bob (although I’m not sure how mutual the feeling is at this point), but it’s good to have the arguments out there to take on.

First up, just to show I’m not plucking facts from the air, here’s that HBF/Lichfields analysis, And here’s a Centre for Policy Studies paper estimating that getting rid of targets could cut housebuilding by 20-40%.

Now let’s go through Bob’s arguments, in his own words.

‘First, in the past half century, the Isle of Wight, like quite a few places in the south and southeast of England, has doubled its population — yet we still export our young people.’

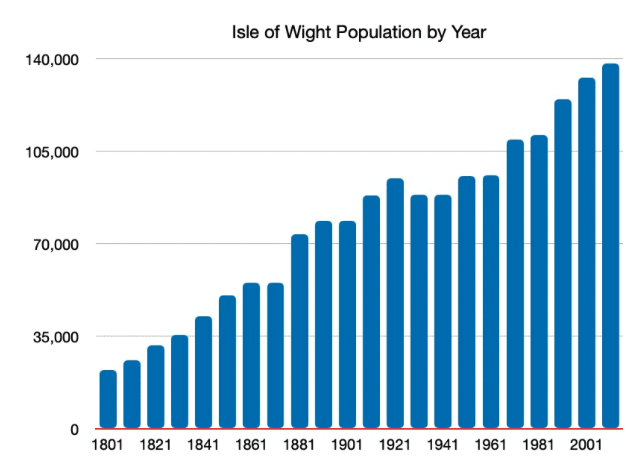

It’s a bit of a shame that Bob’s article starts with a massive statistical blunder. The Isle of Wight hasn’t doubled its population over the last 50 years, or anything close to it, as this chart shows.

.

.

But Bob is right that the population there, and everywhere, has grown. Unfortunately, housebuilding hasn’t kept pace. Since the 1950s and 1960s, the rate at which we expand our housing supply has halved – even as the population has risen. Maybe if we built more, the young people would find it easier to stay?

The ‘landbanking’ fallacy

We then move on to the core of the Tory rebels’ argument.

‘Second, in England alone there are one million outstanding planning permissions — and yet we build homes at snail’s pace.’

The Villiers amendment would dramatically reduce the number of planning permissions being granted, by snapping the three main sticks that central government has to beat councils with – targets, five-year land supply, and a presumption in favour of sustainable development. But, they say, that doesn’t matter, because those selfish greedy builders can run down their existing inventory and actually build the homes they’ve been given permission for.

However, this gets things entirely the wrong way round. This excellent analysis on BuiltPlace explains why the ‘1 million unbuilt planning permissions’ line that the rebels love to trot out is an incredibly dodgy statistic, which doesn’t mean what they think it does. But even then, as housing analyst Ant Breach explains here, the reason builders get so many permissions is because it’s so hard to get planning permission! ‘Land banking’ is not a cause of the housing crisis, but a buffer against the ridiculous unpredictability and torturous slowness of the planning system.

It’s a point we’ve made in our work at the Centre for Policy Studies, and indeed one that was made by the Letwin Review, set up specifically to look at build-out rates. One big factor is that because it’s so hard to get planning permission (including huge fees for lawyers and planners) we are building fewer, bigger sites, which tend to get built out more slowly. Fix the pipeline, and you fix the land banks. (In fact, I should stress – the ‘unbuilt permissions are causing this’ analysis is not taken seriously by anyone who actually works in housing or on planning policy, or at least no one that I’ve come across.)

Greenfield vs brownfield

Returning to Bob’s piece, his other big complaint is about the type of development – greenfield rather than brownfield.

‘Third, despite hundreds of thousands of brownfield planning permissions, the big developers still lazily rely on car-dependent, low density, out-of-town greenfield housing estates, the most unsustainable form of development we have.’

This is the rebels’ other big argument – that there is plenty of scope to build on brownfield land, coupled with a newfangled worry about out-of-town greenfield housing estates and sustainability.

But brownfield is more difficult and more expensive to develop. It is often in the wrong places. It is also where we need/want to build offices, factories, lab space, warehouses etc, which you can often get a lot more money for. We all like ‘brownfield first’, but as the House of Lords – and everyone else who’s looked at this – has found, it’s not a panacea.

What about unsustainable, car-driven development?

Well, for a group that complains an awful lot about ‘top-down housing targets’ being statist and evil, the rebels don’t seem to acknowledge that people have agency. It’s not really very conservative to force them to live where you want them to! And, as the pandemic proved, many of them (especially those with kids) really want to live in nice houses in the suburbs or countryside with their own gardens. The kind of houses that I’m guessing most of the signatories to that amendment live in too.

There’s also a contradiction here. If we assume that Bob wants the opposite of what he’s decrying in his article, his view is that we should be building ‘car-free, high-density, in-town, brownfield apartment blocks’. But his partner-in-crime Theresa Villiers opposes the current system precisely because it results in ‘blocks of flats which are entirely inappropriate in a low-rise suburban neighbourhood like my constituency in Barnet’. Of course, it could be the case that what’s locally appropriate for the Isle of Wight isn’t appropriate for Barnet. But that’s what local plans and local design codes are already for – and they will be strengthened under Michael Gove’s existing plans.

A couple more points here. On sustainability, there is already a requirement that development results in a 10% net gain in biodiversity. People like Thakeham (whose conference I spoke at yesterday) are building carbon-neutral homes with zero energy bills.

Meanwhile, in terms of car-dependence, cars remain absolutely the dominant mode of travel and commuting outside London and the big cities. As Villiers herself says, decreeing that people shouldn’t have them is effectively making it hugely more difficult for them to live their lives and get to work.

Nimby? Me?

Another of Bob’s complaints is that he and other MPs are being unfairly smeared as Nimbys.

‘People like me — there are 107 Tory MPs on the Planning Concern Group and the numbers are growing — are described by our opponents as nimbys who want to prevent development and stop young people buying their first properties. In reality, the opposite is true.’

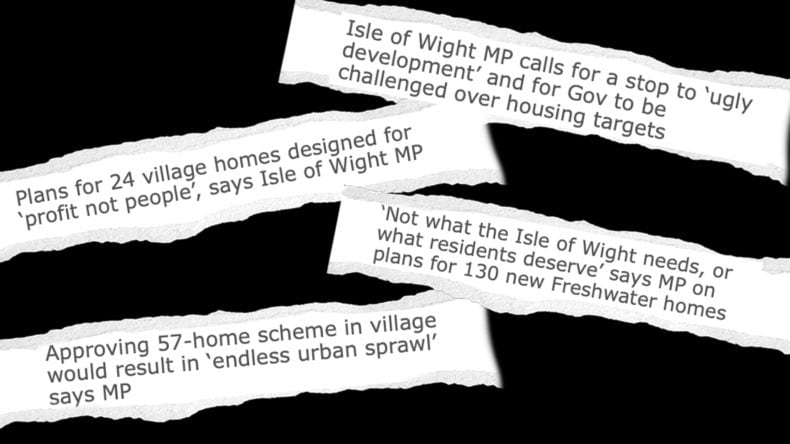

What, Bob, would ever have given people the idea that you were a Nimby? Apart from when you described the 300,000 a year housebuilding target – a commitment in the manifesto you were elected on – as ‘completely arbitrary’, rather than the product of some fairly Googleable maths.

Perhaps your local paper can provide a clue…

.

Bob then moves on to the idea that targets themselves are inimical to the Tory tradition:

‘Yes, we don’t like centrally-imposed, top-down targets — an incredibly unconservative idea if ever there was — and we despair of lonely, ugly, soulless out-of-town development. But we oppose these things because we want a planning system which is environmentally sustainable, is rooted in our communities and is used to regenerate our towns and cities, not hollow them out.’

However, as I pointed out the other day, if you think top-down targets are incredibly unconservative, why aren’t you objecting to green belts, or national parks, or indeed the existence of a planning system, on the same grounds? They’re all deeply unconservative. But only one forces you to build in your local area.

That said, regenerating towns and cities is a great idea! We at the Centre for Policy Studies have suggested that every local plan should begin with an analysis of how much vacant retail space each town/city has, and the scope to build more by turning commercial property into residential. Yet, oddly, we think you can also do that without destroying the rest of the planning system.

Bob, meanwhile, takes issue with the idea that he is some kind of instinctive naysayer.

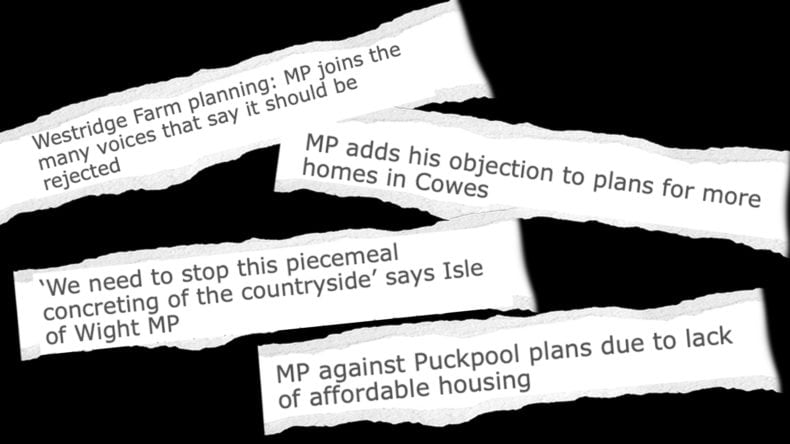

‘Our opponents accuse us of saying no, no, no to new ideas. In reality, we love saying yes, yes, yes to great ideas that will help home building, encourage communities and protect the environment.’

I can’t imagine why people think you like saying ‘no, no, no’…

.

In the interests of brevity, we’ll skip through the rest of Bob’s points. It’s worth saying, he does have some reasonable suggestions for getting more homes built. For example:

‘Many of us want more compulsory purchase powers for councils, to be debated today, to slap purchase orders on long-term derelict or unused buildings, especially ones important to communities. On the Isle of Wight, there are too many derelict hotels which stand empty for years — some of which mysteriously catch fire — and which could be converted to flats for islanders. These buildings, in Sandown, Ryde and elsewhere, blight communities. There are examples in every town and city in the UK.’

This is a great idea – but, again, it doesn’t require destroying the existing planning system. It is worth pointing out, however, that derelict buildings are usually derelict because it isn’t cost-effective to develop them, not because of some mysterious plot to destroy Britain’s green fields.

Then we’re back to familiar territory on greenfield vs brownfield.

‘Many of us also want a system that changes the economics between greenfield and brownfield sites. We need to incentivise brownfield and disincentivise greenfield building. Sadly, in the past decade we have done the opposite. Sadly, in the past decade we have done the opposite. It’s easier to build on greenfield rather than regenerate brownfield. If we are serious about the environment, not to mention being able to grow food in this country, why on earth have we allowed this?

The issue here, as I noted above, is that brownfield is by definition harder to develop, because it’s already got things on it – like industrial contaminants. Fixing that requires spending serious money. We should also remember that when Bob and his colleagues forced Boris into U-turning on his manifesto commitments on housebuilding, Bob didn’t say he wanted to ‘disincentivise’ greenfield development – he wanted to ban it, even when permission had already been granted.

As for the ‘being able to grow food’ point – which is a huge issue for the likes of Damian Green – it’s worth pointing out that since 1979, the area of green belt in England has more than doubled, covering more than 10 times as much land as bricks and mortar. That ratio rises to 30 times when you include national parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and other protected sites. And if you’re worried about food security, why not abolish the biofuel mandate and build on the land you’ve freed up?

A question of character

Finally, we come to the important issues of ‘character’ and developers’ responsibilities.

We love our communities too! We want them to be able to oppose developers on grounds of character, so that we can help clean up the system. Why should people who abuse the system, or engage in environmental vandalism or ignore or threaten residents, or repeatedly fail to develop property, not be challenged on their track record or behaviour?

And we want a community right of appeal to shockingly inappropriate development. If developers can appeal, why not readers of The Times?

Now, these both sound like good ideas at first. The problem, as Planoraks points out, is they both add extra levels of cost, complication and delay to the system

If you have a ‘character test’ for builders, how do new entrants ever get started? As for a ‘community right of appeal’, that means development can be challenged at the local plan stage, the grant of outline planning permission, reserved matters, and then yet again.

And as with so many of these changes, the extra cost and expense mean that only the big companies who can afford the legal and planning fees will be able to navigate the system – entrenching their dominance rather than challenging it.

I really don’t want to be mean to Bob and others who support this amendment. I know they are responding to genuine challenges, and genuine pressures, in their constituencies.

But their proposals will axiomatically, inevitably, self-evidently make it harder to build and reduce planning supply – there is literally no argument about that, unless you resort to the ‘unbuilt permissions’ line which is demolished above.

And while they do have some good ideas about how to bring the system closer to the people and fix individual constituencies’ problems, they never explain why you need to destroy the existing system, across the entire country, in order to introduce them.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.