On CapX last week, I wrote about the unfolding military coup against Zimbabwe’s longtime ruler Robert Mugabe. Deserted by his erstwhile supporters and facing imminent impeachment in that country’s Parliament, the 93-year-old dictator finally threw in the towel and resigned earlier this week.

He will, it seems, be allowed to live out his remaining days in Zimbabwe and continue to enjoy the luxurious properties that he amassed during the 37 years in power. Judging by the spontaneous outburst of joy throughout the impoverished and tyrannised country, Mugabe’s resignation came none too soon.

Amid the celebrations, the BBC published an article titled, “Robert Mugabe: Is Zimbabwe’s ex-president a hero or villain?” My initial reaction was to dismiss Joseph Winter’s piece as yet another example of left-wing bias at the BBC. Zimbabwe, after all, is a ruined country. Upon reflection, however, the article seems to me to reflect a deeper truth – put plainly, people prefer to be mistreated by rulers who look like them, rather than be relatively well-governed by people perceived as foreign.

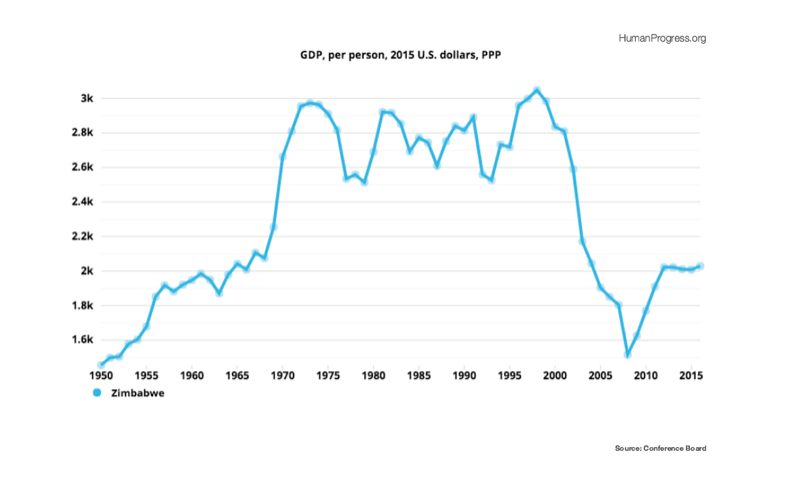

First, let’s briefly look at Mugabe’s legacy. Since coming to power in 1980, the dictator presided over years of economic stagnation and, eventually, decline. Judging by the data, incomes in what was then Rhodesia, roughly doubled between 1950 and 1973. Following the outbreak of the Bush War (i.e., the African struggle for independence from the European rule), incomes declined, but quickly rebounded after the end of hostilities and onset of majority rule. That’s where they remained until Mugabe’s catastrophic decision to expropriate commercial land in the early 2000, which wiped out half-century of income growth.

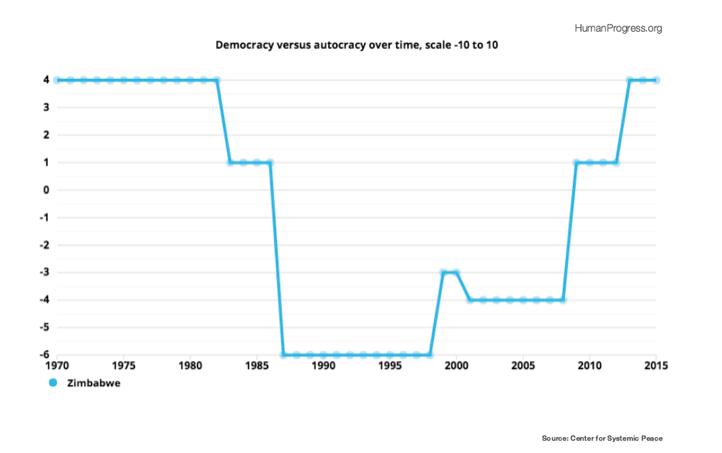

That decision was politically motivated, for farmers were largely supportive of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change. That brings me to the dictator’s political legacy. It may seem extraordinary, but Rhodesia was politically freer than Zimbabwe. To be crystal clear, political freedom does not mean racial equality. Rhodesia’s political system ensured that Europeans remained in charge. But, in terms of the rule of law and government accountability to the electorate, Rhodesia was more democratic than Zimbabwe was after the first two years of the majority rule (i.e., the time Mugabe needed to consolidate power).

So, objectively speaking (my economic data comes from the Conference Board and my political data comes from the Center for Systemic Peace), Zimbabweans were freer and experienced more rapid economic development during the minority rule than was the case under the majority rule. This was not an uncommon development. Following independence in the 1960s, many African countries saw both political and economic retrenchment. Rare is a country, like Botswana, which remained both democratic and grew more prosperous after the end of the colonial rule. These are, regrettably, empirical facts and not, as some might conclude, a pean to colonialism, which I oppose.

Second, Zimbabweans themselves are clearly conflicted about Mugabe’s legacy. As Winter writes in his BBC article, “For some, he [Mugabe] will always remain a hero who brought independence and an end to white-minority rule. Even those who forced him out blamed his wife and ‘criminals’ around him. But to his growing number of critics, this highly educated, wily politician became the caricature of an African dictator, who destroyed an entire country in order to keep his job.” So, was the end of the minority rule worth the destruction of the country’s economy and erosion of its political institutions?

This is not an easy question, but Isaiah Berlin’s 1958 inaugural lecture at Oxford University titled “Two Concepts of Liberty” may provide an answer. In that essay, Berlin wrote:

I may feel unfree in the sense of not being recognised as a self-governing individual human being; but I may feel it also as a member of an unrecognised or insufficiently respected group: then I wish for the emancipation of my entire class, or community, or nation, or race, or profession.

So much can I desire this, that I may, in my bitter longing for status, prefer to be bullied and misgoverned by some member of my own race or social class, by whom I am, nevertheless, recognised as a man and a rival – that is as an equal – to being well and tolerantly treated by someone from some higher and remoter group, who does not recognise me for what I wish to feel myself to be.

It is this desire for reciprocal recognition that leads the most authoritarian democracies to be, at times, consciously preferred by its members to the most enlightened oligarchies, or sometimes causes a member of some newly liberated Asian or African state to complain less today, when he is rudely treated by members of his own race or nation, than when he was governed by some cautious, gentle, well meaning administrator from outside.

I think that Berlin is, probably, correct. Rhodesia may have achieved better economic outcomes than Zimbabwe, but those came at a cost of denying the African majority its desire for self-determination. The sorry history of Zimbabwe, then, reminds us of an obvious fact: people are not machines carefully evaluating merely the material costs and benefits of their actions. They are beings driven by passions, which can lead to outcomes that are far from optimal.