This week’s mud-slinging between Westminster and Brussels was ultimately about one thing: money. Britain has it. Europe wants it. In fact, the only way for the European Union to meet its financial commitments – and to avoid an unholy row among its members – is to squeeze Britain for as much as it can get.

The key thing to understand, however, is that this doesn’t just apply to the so-called “Brexit bill”. Any deal between Britain and Europe is almost certainly going to include some sort of fee for access to the single market, or to the most important parts of it. It may be dressed up as an administration fee, but in reality it will be a straightforward greasing of the wheels.

The question, then, is what access to that market is worth. And a trio of academics have come up with a surprising answer.

Earlier this week on CapX, we ran a fascinating analysis of why people actually voted for Brexit, based on a new book by Harold Clarke, Matthew Goodwin and Paul Whiteley.

The book’s main focus is the shifting state of public opinion on Europe over the years, and the factors which drove the vote. But it also contains a startling claim – one so shocking to Europhile orthodoxy that the Financial Times apparently refused to print it.

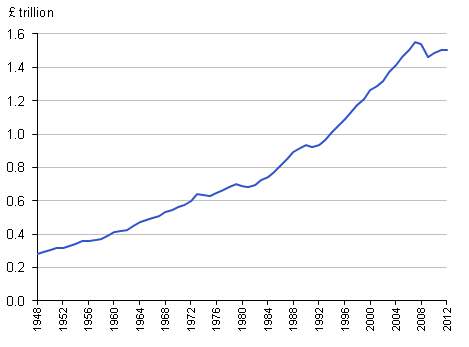

The authors scrutinised the performance of the British economy over the past 64 years, to find the factors that hampered or boosted growth. And EU membership was not one of them.

The three authors are, admittedly, political scientists rather than economists – and other experts have found differently (and will doubtless dispute these new findings). But no matter what variable or model they use, they say, they cannot see how joining the European Economic Community in 1973 made a lick of difference to growth rates.

UK GDP, adjusted for inflation. Source: Office for National Statistics

This may be connected to another of their findings, which is that a greater volume of trade tends to be a symptom of growth rather than a cause. What really shifts the economic needle, they insist, is a nice, low pound (of precisely the kind that Brexit produced).

As if this wasn’t enough, Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley make another, equally striking claim: that EU membership hasn’t been that great for anyone else, either.

For 20 out of 28 member countries, growth actually dipped after joining rather than rose. And with the exception of Ireland and Luxembourg, those eight exceptions were all post-Soviet economies with significant “catch-up” gains to make.

Of course, to claim that Britain has not gained from the Single Market is not the same thing as saying that we will be unscathed if we leave it. While it may not have changed the size of our economy much, it has certainly altered its shape.

In sector after sector, firms have structured their operations and supply chains around the assumption of unfettered mutual market access, and would greatly prefer that it continue. Likewise, our economy (and public services) have come to depend on high-skilled and low-skilled immigration, primarily from Europe.

But these findings do suggest several important things. First, access to the Single Market may be worth quite a bit less than Europe will demand for it. Second, the “Project Fear” predictions that Brexit would depress household incomes over a period of decades were (as many said at the time) grotesquely exaggerated. And third, that our own domestic decisions matter just as much for our economic future as the precise shape of our trading arrangements (a theme I’ve been nagging away at for a while now).

They also, in a way, bring the Brexit debate full circle. We always scoffed at those on the continent who claimed the European Union was about delivering peace rather than prosperity. Our relationship with it, we boasted, was strictly transactional rather than ideological.

When we left, it was because we felt that deal was no longer delivering. If Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley are right, it never really did.

This article is taken from Robert Colvile’s weekly email briefing for CapX, which also includes a round-up of our best stories. Sign up here.