Those with pro-market leanings are not having a good time of it at the moment. In Britain, the Labour government is taking the largest share of the economy in tax that has ever been sought in modern times. In the US, Donald Trump’s tariff policy involves the most explicit repudiation of pro-trade concepts since World War II.

Across much of the developed world, including Italy, the Netherlands, France and the UK, the political Right is becoming less liberal and more populist, and in the process deviating more and more from the Reagan-Thatcher model of the economically pro-market, pro-trade Right.

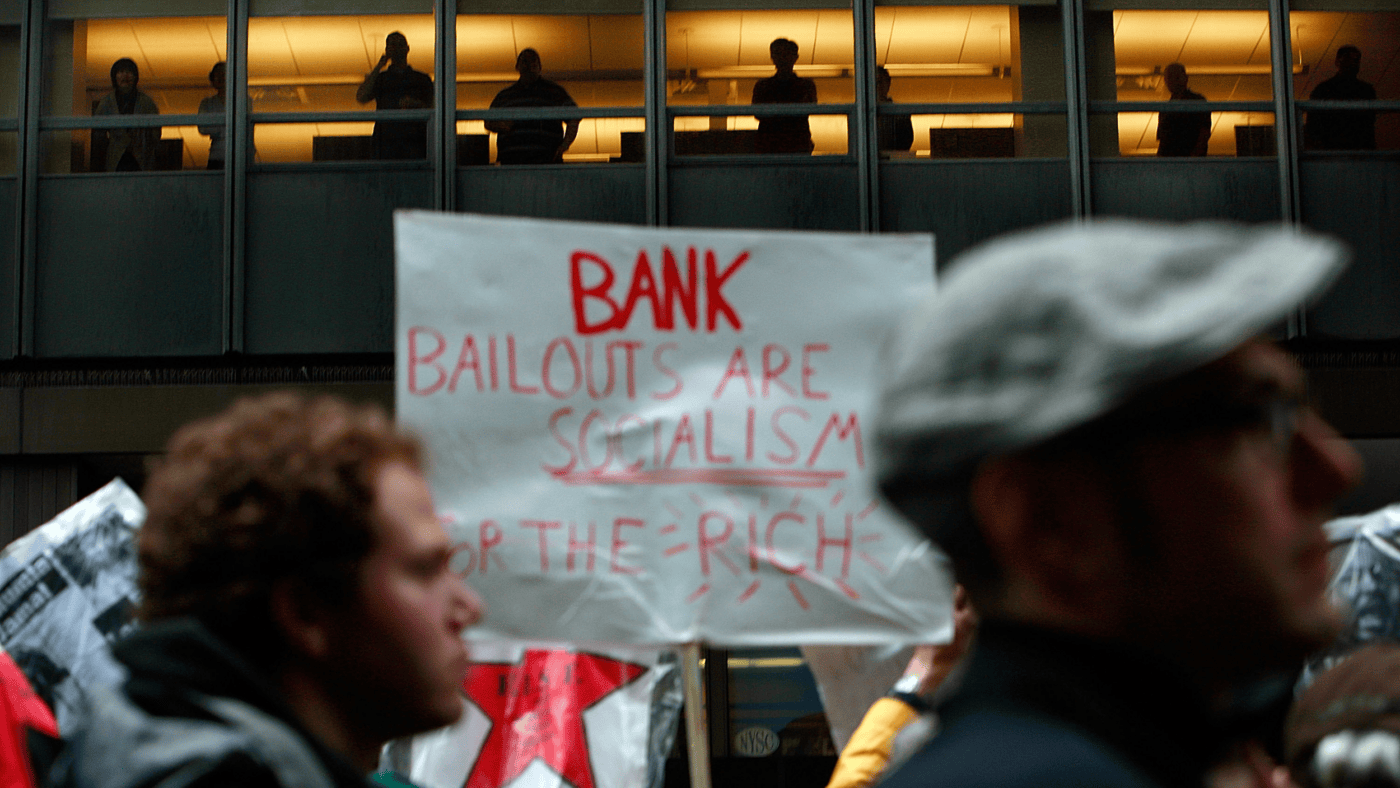

Champions of economic liberalism urge a fightback, a more muscular assertion of pro-market ideals. But in doing so they face a huge philosophical hurdle, to which they typically as yet have no answer. That hurdle is that the origin of the travails of economic liberalism is the bank bailouts. With no robust and credible answer as to how the economic and financial system should be redesigned so as to ensure that bank bailouts can’t happen in future (indeed, there were bailouts again in the US as recently as 2023), economic liberals are at the end of the day defending a system that is, at its core, profoundly economically unjust and that everyone can see is unjust and thus is beset by insurgent campaigns seeking other policy measures (which by their nature are anti-market) to offset or mitigate that injustice.

Let us understand a little more of why the bank bailouts are the source of our current problems. In the UK, the issue actually began slightly earlier, with interest rate and housebuilding policies of the mid-2000s being geared towards preventing a house price crash. That began the process of sacrificing both the health of the overall economy and the opportunity to get ahead for those that currently did not have wealth, in order to defend the position of those that already had things – even if the latter had made mistakes.

When people debated the merits of avoiding house price crashes or banks going bust, they always focused on the interests of those that already had. If you owned a house or you had bank deposits or a pension, then you counted – it was the government’s job to intervene to prevent you from losing what you had. But if you didn’t have – if you rented and would have liked to buy a house if prices fell, or if you weren’t yet endowed with enough wealth to have large bank deposits – then you were irrelevant.

When the government intervenes to prevent the people who already have from losing out, such intervention by its nature reduces the opportunities for those who do not yet have. So as well as the bank bailouts and other policies over the past fifteen to twenty years arguably having sacrificed long-term growth (growing the pie) in order to seek to reduce the depth of short-term downturns (I believe this to be clearly true, but the point is at least debatable), such policies have also unquestionably denied opportunities to the economically less advantaged in the form of reallocation of a given amount of wealth (carving up a given pie).

Once the bailing out threshold was crossed in the bank bailouts, it has subsequently come to be the norm, in a stream of interventions right through to the huge energy packages of 2022/23. Whatever the existing economic order is, the role of policy seems to be to try to stop it from changing.

People feel the injustice of this, and that has driven politics of two forms. For a time, anti-market sentiments on the Left verged on the communist. More recently, the anti-market sentiments of the populist Right.

It’s not enough for pro-market people to declare that markets are efficient, promote freedom, promote innovation and growth and so on, when everyone knows that the outcomes produced by the interplay between politics and markets are that those with wealth and power use their political influence to protect themselves from the economic consequences of their mistakes or of any loss, while as a consequence excluding those that lack wealth and power from opportunity. That problem becomes even more exacerbated when the political system responds to the poor growth, weak birth rates and risk of social stagnation that such interventions create by using mass immigration to seek to replace the dynamism that bailouts have snuffed out.

The natural response is that those who are marginalised – those who were denied opportunity by state interventions – seek to have their own state interventions to rebalance the scales.

Pro-market thinkers need to grasp that in a world in which politics means markets lead to mass bailouts to protect the vested interests of the already-wealthy, the ‘pro-market’ argument is the defence of economic injustice. In order to avoid that, we (and I mean we – I am pro-market too) need robust, politically credible answers to how bailouts will be avoided in future. We cannot pretend the problem of bank bailouts will go away if we avoid talking about it for long enough.

It is not enough for politicians to say they want to avoid future bailouts, even if they really mean it. People can’t be expected to rely on politicians’ good intentions. We need to reform the system so governments (of whatever political persuasion) won’t be able – and won’t even want – to bail out the wealthy ever again.

Until we accept that we have to repudiate bank bailouts and we need to offer proper, implementable solutions to re-design the economic and financial architecture so bank bailouts are not attractive to policymakers in future, we will not get a hearing from either Left or Right, and we will not deserve to.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.