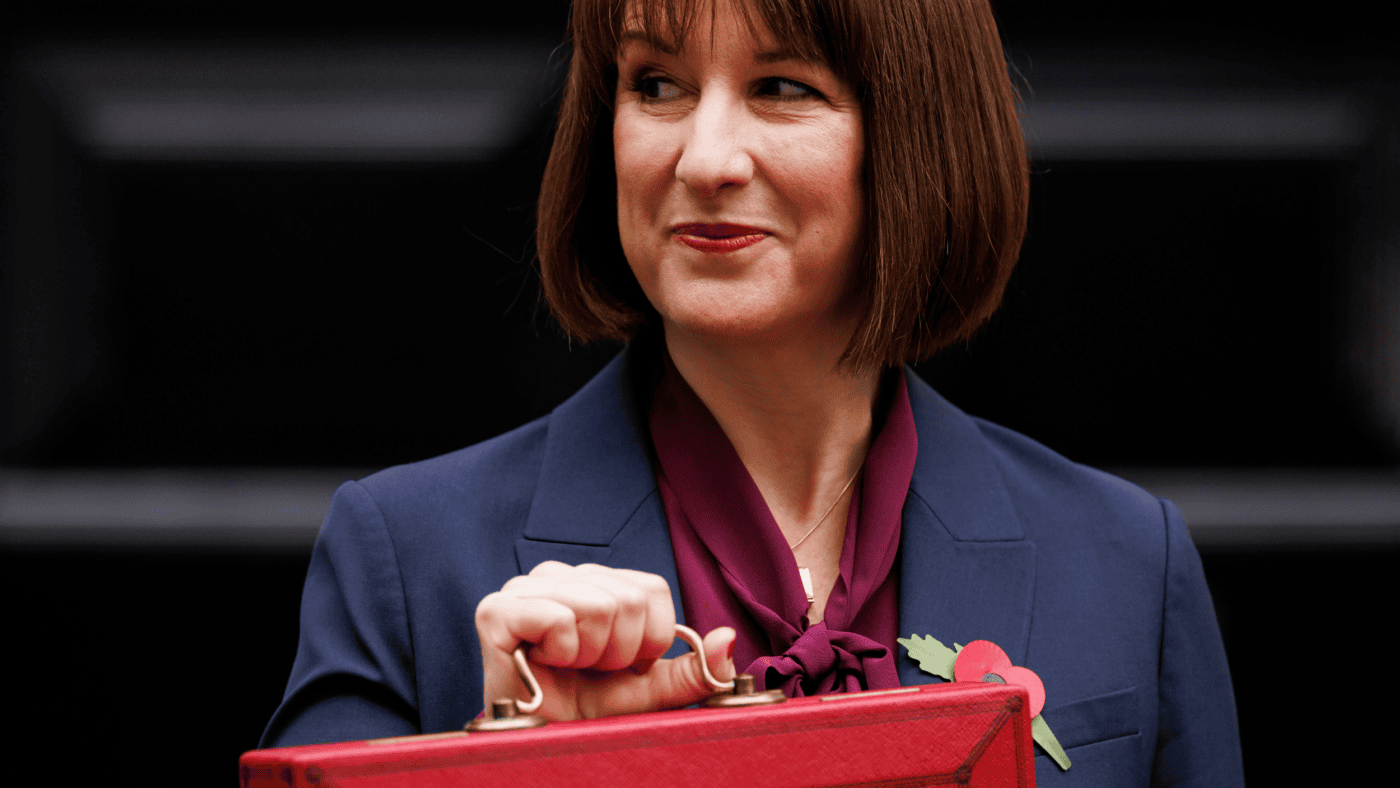

Rachel Reeves’ Budget involved major changes. This was no mere tweaking. There was no ‘steady as she goes for the first couple of years to see where we are’, akin to the early period of the Blair government in which it initially matched Tory spending plans. Instead, Reeves has opted more for a ‘go big or go home’ approach. Over the review period, spending is scheduled to rise by £79 billion, of which £64bn is to occur by March 2026, or 17 months from now. Tax is rising by £40bn as the direct result of changes and a further £12bn indirectly. Public sector net debt is scheduled to be 5% higher as a result of her measures – about £170bn of extra debt.

Taxes were already scheduled by the Tories to reach their highest level since the 1940s. Reeves’ plans take us beyond even the 1940s levels, some 4% of GDP more than the UK economy has ever yielded on a sustained basis. It must be seriously questioned whether the UK economy is actually capable of producing that much tax. Set aside the ‘oughts’, the ‘nice-to-haves’ and the ‘long-term concerns’. Even if one were completely convinced that it was morally and economically fine for national account taxes as a share of GDP to be above 38% of GDP and stay there, instead of the 34% and less that the UK economy has peaked at ever since the 1940s (with one surge to 35% in the late 1960s), there would still be the question of whether it is possible.

The UK economy, with its combination of secure property rights, no retrospective taxation, relatively modest (albeit not especially low) taxes and pleasant living opportunities, has long attracted a disproportionate share of the world’s internationally-mobile high-income workers and capital. That makes our economy more sensitive than the economies of certain of our Western European peers to tax rises. Attempts to raise tax beyond a certain point tend to make high-income workers and capital leave, as well as making those who stay less inclined to tax-generating activities.

If we were to raise tax rates high enough for long enough, doubtless our economy would eventually adjust, with our industrial mix changing to involve fewer mobile, high-income workers (in legal services, management consultancy, finance and so on) and less asset management. But in the meantime, tax revenues wouldn’t rise, so they wouldn’t be available to cover the gap between Reeves’ spending plans and the levels of tax that can actually be generated.

If Reeves’ tax rises don’t actually increase revenues by nearly as much as her Budget needs them to, she risks rapidly getting into debt problems. Debt is already scheduled to be very high, at just under 100% of GDP, and barely falls in the Budget. If the hoped-for tax revenues do not materialise, that debt pile will rise rapidly, unless GDP rises faster than the tepid 8% growth over the Parliament that Reeves’ official forecasts suggest. It is not impossible she could get lucky, with AI and other new technologies stimulating an unscheduled growth burst. But without that, if the tax revenues do not appear, the debt situation will start to look very grim very fast. Indeed, the OBR itself assesses that Reeves has only a 54% chance of meeting her own (now looser) fiscal rules.

Reeves appears to hope that her plans to raise government investment and to establish partnerships between government and private investors to steer growth to desired sectors and locations will help the economy grow faster. That seems unlikely. The UK economy does have poor investment, but that is because planning rules make infrastructure projects intractable and because mass immigration makes labour-intensive business models more attractive than more capital-intensive business models. The Budget’s large rises in business taxes are projected to make business investment lower, not higher. Perhaps the much-vaunted planning changes might yet help to turn that around. But as to the Budget itself, the OBR’s assessment is that it does not boost medium-term GDP growth at all.

A more plausible path might be boosting GDP growth through enhancing public sector productivity. There should be ample scope to achieve that, and it should be fertile territory for Labour given their good relations with the public sector unions. But whether this Government can make it happen very much remains to be seen. Another potentially promising area would be increased regional fiscal autonomy (again natural Labour territory, given their strength in local and regional government), where the UK’s highly centralised fiscal arrangements may, according to OECD studies, be holding back our growth and the Budget announced some (albeit very modest) changes.

There are many other measures the Government could be taking that should enhance growth, including a number, like the examples above, that are wholly consistent with Labour philosophy. We do not need to despair totally, yet. However, relying on solving our very difficult fiscal situation by raising taxes to levels, relative to GDP, well above any our economy has ever sustained for any period of time is extremely perilous and, in my view, liable to fail. This Budget may have seemed like a set of once-in-a-political-generation fiscal policy announcements, but I suspect it will be only the beginning…

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.