Could the collapse of confidence in central banking, which has been so in the news the last few weeks (and years), reinforce the maneuvering of governments toward doing away with cash — or vice versa? That’s the question that nags at me after reading the column by the American editor of the Financial Times, Gillian Tett, on the benefits of doing away with what the French like to call “liquide.”

This issue is often discussed in terms of the government’s attack on freedom and property rights. It wants to force all transactions to within reach of the hard-pressed tax authorities. Tett doesn’t ignore this element of the debate. But the fascinating feature of her column is its context in the current crisis over the inability of central banks to return monetary policy to normal.

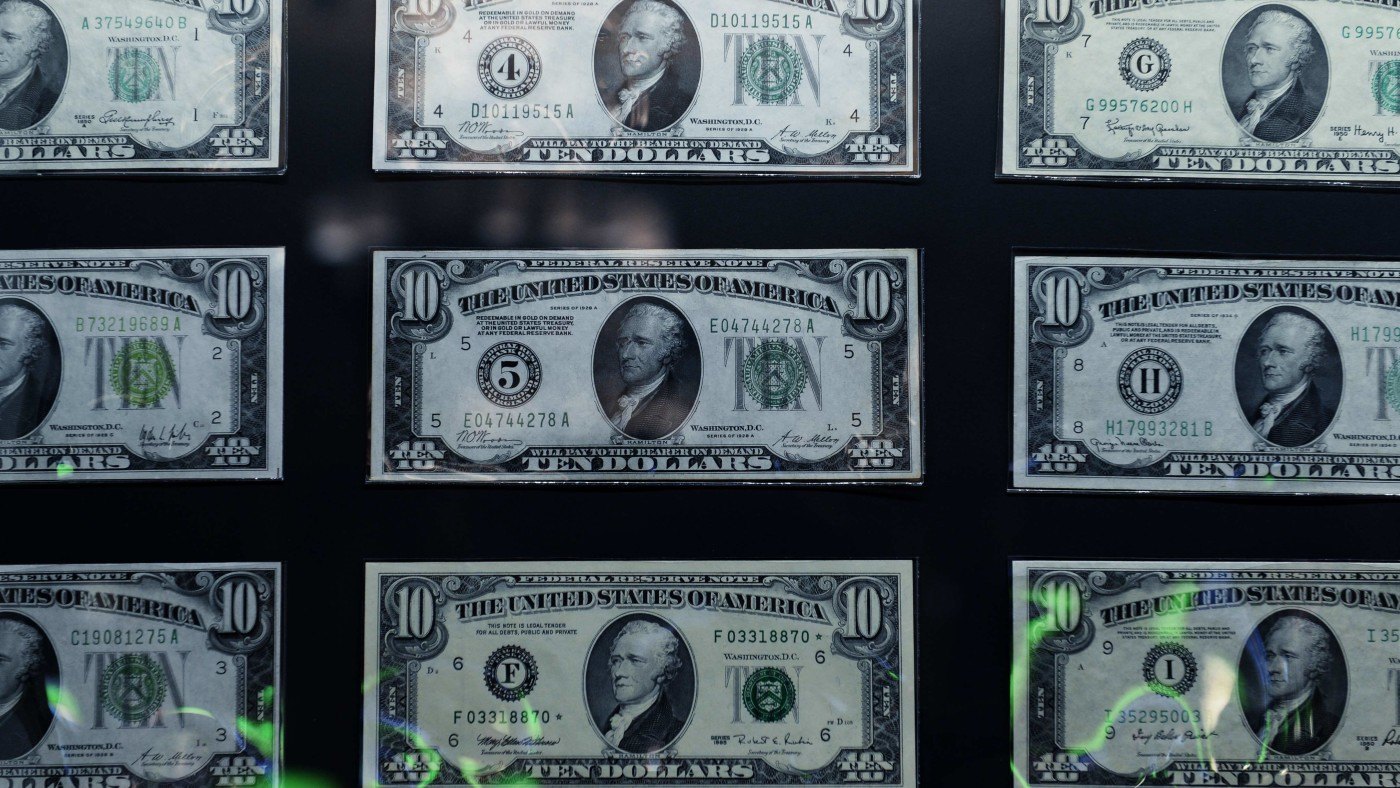

Tett pegs her column to remarks at Davos by Deutsche Bank’s co-chief executive John Cryan, who “cheerfully predicted” that a decade hence “cash probably won’t exist,” Tett writes. Adds she: “Yes, you read that right: all those grubby greenbacks and tattered euro bills in your wallet are heading for the dustbin of history.”

“There is no need for it,” she quotes Cryan as declaring about a standard central bank liability.

Tett is not entirely convinced; she argues the data don’t support it. She acknowledges that the use of cash has been declining with the rise of electronic finance. She cites the Bank for International Settlements, which reckons that cash in circulation in the largest 19 economies has plunged to 7.9% of GDP in 2014 from the 8.4% at which it was running in 2010.

Tett is more struck by how slow the trend has been — and by the fact that the total volume of cash has been rising in the leading Western economies, save for Sweden. “Those smartphone bank accounts and innovations in blockchain technology might look flashy but they have not killed off paper money,” she writes. “Yet.” I like that “yet,” even though I’m not sure technology is the driver here.

What I think of as the driver in the trend away from cash is the logic, or illogic, of fiat money. Tett calls an “unintended consequence of super-loose monetary policy” the “reduced incentives for consumers to store their money in banks.” Or, I’d add, to use government issued money at all. It’s just hard to see how this can be divorced from the question of how, say, the dollar is defined in law.

Economist Kenneth Rogoff, in an oft-cited 2014 paper on the possible phase-out of cash, suggested that scrip has been “surprisingly durable, even if its major uses seem to be buried in the world underground and illegal economy.” That depends on what one means by durable. After all, the actual value dollar today, at less than a 1,200th of an ounce of gold, is off more than 97% since the end of Bretton Woods.

In any event, the central banks seem to be getting less and less respect. Within days of issuing Tett’s column, the FT was out with an editorial called “Central bankers peer into uncharted waters.” It noted that the Bank of Japan’s “surprise move into negative interest rates” is “swiftly unraveling,” while experiments with same in Denmark, Switzerland, and the Eurozone “have yet to provide definitive conclusions.”

Then, Fed chairman Janet Yellen was on Capitol Hill, only to get into an argument with that arch-right-winger (not) Rep. Maxine Waters. The streaming headline on the Drudge Report — ‘PANIC: GOLD LINES ‘ROUND THE BLOCK’ RECESSION FEARS MOUNT – linked to a story in the London Daily Telegraph headlined: “Investors ‘go bananas’ for gold bars as global stock markets tumble.”

It reminds me of the day the Wall Street Journal reported that a faction in Congress was itching to enact a law requiring the government to sell the gold in Fort Knox. It prompted me to call the greatest constitutional sage on the dollar, Edwin Vieira Jr., and ask him: “Ed, do you think the government should sell the gold in Fort Knox?” Without pausing, he boomed: “Don’t use the world ‘sell’!”

“Gee, Ed,” I said, “what word should I use?” “Spend,” said the author of the definitive two-volume tome, Pieces of Eight. “You don’t sell gold, you spend it.” I said, “Hmmmm,” or something to that effect. That’s when Vieira uttered what I think of as the most important thought to bear in mind in this crisis. “Gold,” he said, “is the money.”