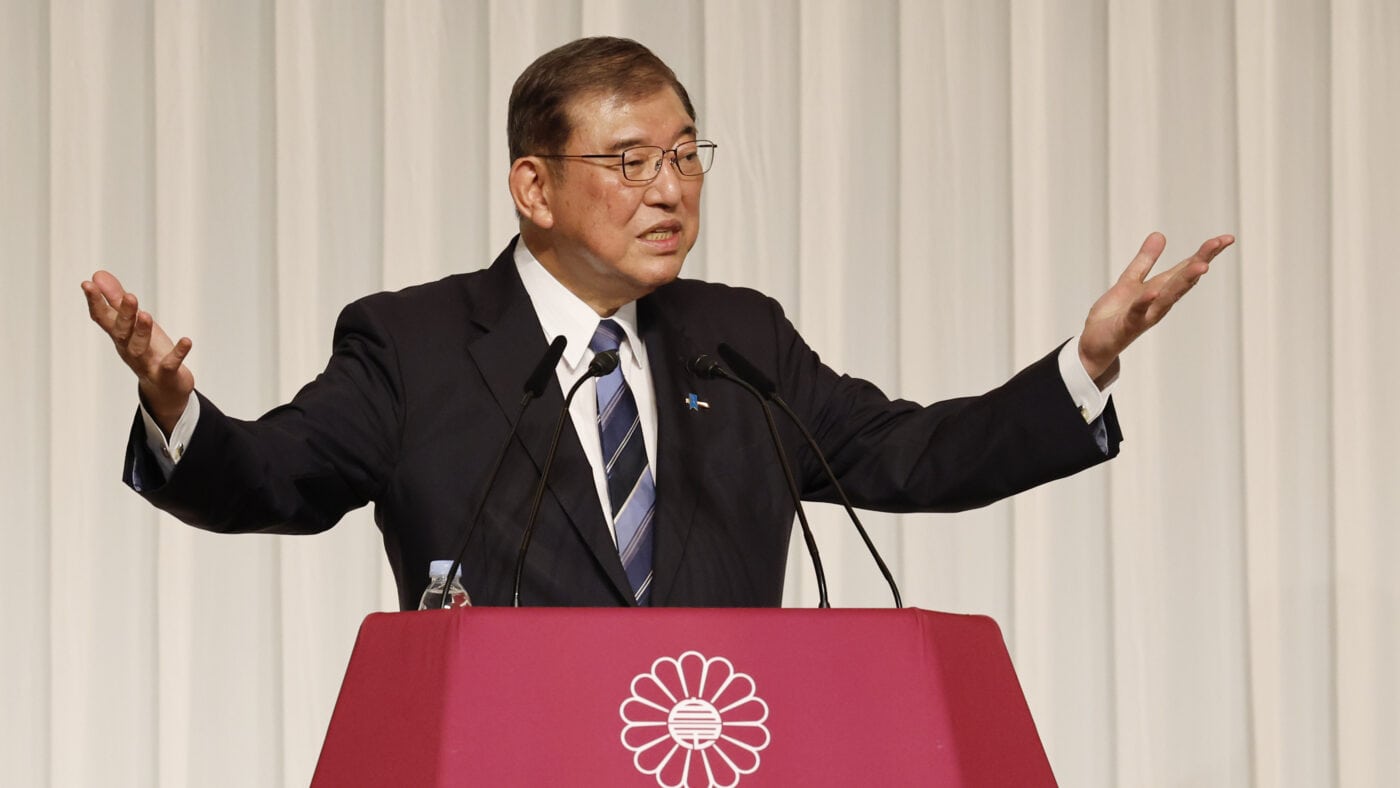

How happy are the Japanese? This question appears to be at the heart of the new Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s plans for his administration. So concerned is Ishiba with his countrymen’s mental well-being that he plans to quantify it scientifically through a ‘happiness index’. Ishiba’s new policy was considered important enough to be trailed ahead of his first major policy speech last week and looks set to be a talking point in the run-up to the snap election he has called for 27 October.

How exactly the new PM intends to gauge the happiness of the Japanese people is unclear, but he may draw on existing models. The Global Happiness Index (GHI), which has been running for 12 years and has issued four reports, utilises WELLBYs (nothing to do with the archbishop) which indicate the well-being of an individual taking into account life expectancy, freedom, generosity, social support and health. The GHI now encompasses more than 150 countries. Japan’s tally of WELLBYs puts it in 51st place (the UK is 20th, Finland is 1st).

Happiness indices have a mixed record, though. The UK, which has been attempting to measure happiness since David Cameron brought in the policy in 2012, finally abandoned it in January. A common criticism is that the figures are derived entirely from surveys, by simply asking people how happy they feel. This is a problem. Even with anonymity, the excruciatingly modest Japanese are the least likely people in the world to boast of their success (and happiness is a kind of success) for fear of appearing arrogant.

Even if some kind of plausible measurement of Japanese happiness can be arrived at, how will Ishiba seek to raise it?

It might be a good idea to first identify the source and likely cause of Japanese unhappiness: it is not immediately apparent. Anyone strolling through Tokyo of an afternoon might conclude there seems to be quite a lot of joy around. From the gaggles of gleeful schoolgirls to the well-preserved seniors shopping happily for groceries or gathering for their neighbourhood culture classes, the atmosphere is far from gloomy. Then there are the relentlessly upbeat TV shows and commercials with their manic presenters and super-smiley actors, which as great student of Japanese life Donald Ritchie observed, appear like manic depressives on the upward phase.

There is plenty of misery though. It is just well-hidden in the workplace. When the golden gates of (extended) childhood finally close, at the end of university (three or four years of fun for most), the grim world of work, responsibility and duty beckons, and with it, for many, a world of pain.

This has already been quantified. Research by Gallup found that a mere 5% of Japanese workers felt ‘engaged’ (involved and enthusiastic) with their jobs, which puts Japan in the bottom third of 140 countries and rock bottom of the G7. Japan has one the highest ratios of psychiatrists per capita in the world, with many patients being stressed out salarymen/women. There were nearly 3,000 work-related suicides last year.

The problem seems to be a combination of absurdly long hours, stifling workplace etiquette, and ultra-short (often unclaimable) holidays, making offices grim incubators of despair. Even casual conversation is frowned upon in many workplaces. Japan is one of the few advanced countries that didn’t produce its own version of BBC sitcom ‘The Office’ – the horseplay and banter just wouldn’t have translated.

Even low paid casual workers aren’t allowed much fun. In my early days in Japan, I made several attempts to interact with shop staff, which invariably fell flat. Once, in a hair salon, unable to communicate my preference, I unwisely attempted humour. My ‘George Clooney kudasai (please)’ was met with such a stunned and panicked reaction from the stylist that I realised my cultural error and never repeated it. Enoch Powell, who once answered ‘how do you want your hair cut?’, with ‘in silence’ would have felt right at home.

If Ishiba can get to grips with Japan’s workplace woes (a big ‘if’, it has been tried), he may make some progress, but for now, it is unclear how serious he even is about his happiness index. Cynics have suggested it may be an early sign of desperation, a frantic grasp for some signature policy (like Theresa May’s abortive Department for Burning Injustices) to distinguish an uncharismatic and unexciting politician from his peers.

Or perhaps it’s an early acknowledgement that in sclerotic, heavily indebted Japan, progress measured in the conventional way will be almost impossible to achieve; so new metrics which appear to show success are required. Ishiba may already be thinking that his best chance of a retirement boast is to leave the country, statistically, a little bit happier.

If he is serious about the policy, though, we could be in for some fun. Perhaps, as in previous government attempts to reengineer society, Ishiba will commission a cute mascot character (‘Happy-chan’?) to promote it. Or we may see a happiness thermometer to give people a visual representation of the country’s mood.

This would at least provide some light relief, boosting the happiness level a fraction, and thus, in a roundabout way, justify the policy.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.