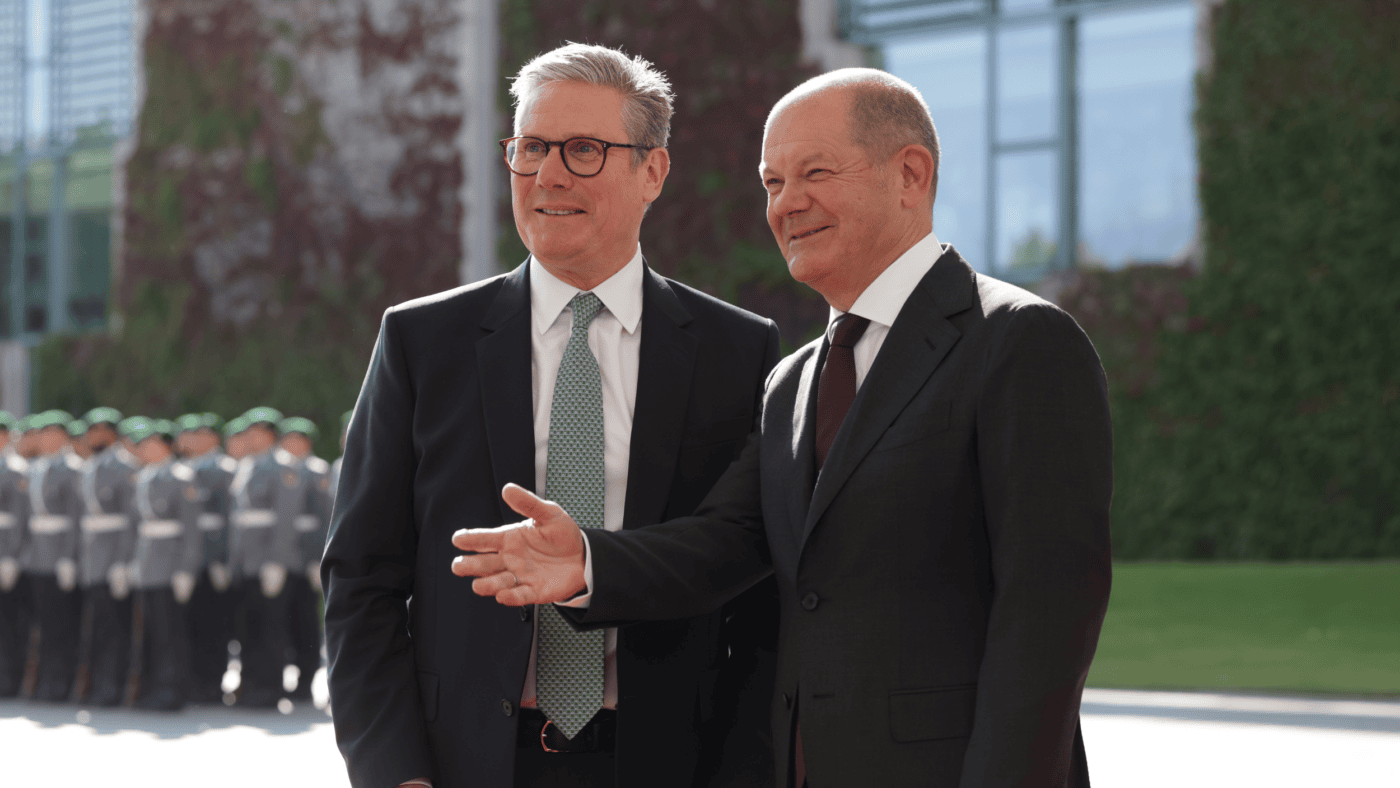

The Prime Minister is in Germany, his first visit to the country since taking office last month, and it is inevitably being billed as an opportunity to ‘reset’ the United Kingdom’s relations with Europe. Keir Starmer has met the Chancellor of Germany, Olaf Scholz, four times already since 5 July, but this is a set-piece bilateral meeting from which every ounce of publicity and meaning will be squeezed.

The new Government has devoted considerable energy to its relationship with Germany. The Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, has visited Berlin, and John Healey, the Defence Secretary, during a dash round Europe, concluded a joint defence declaration between the UK and Germany at the end of July. It is a largely empty agreement, full of high-sounding platitudes and ambition but devoid of concrete measures, but Healey promised that it would ‘kickstart a deep, new defence relationship, built on our nations’ shared values’.

In one sense, of course, it is inevitable that any British government will seek to court Germany’s good offices. The Federal Republic is the biggest state in the European Union and its largest economy, the world’s third largest importer and exporter, and in political and economic terms it makes the weather for the EU. Starmer and Scholz are keen to agree a bilateral agreement on defence co-operation, trade and illegal migration, among other issues, and look towards the Anglo-French Lancaster House treaties agreed by David Cameron and Nicolas Sarkozy in 2010 as a model.

We should also not overlook that Olaf Scholz is a social democrat, and his Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) is Europe’s oldest mainstream left-wing party. This matters to Starmer when France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Hungary, Austria, Czechia, Sweden, Finland and others are all led by centrist or right-wing leaders: the only other major EU member state to have a socialist administration is Spain, whose Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, is currently also president of the Socialist International.

Despite all this, Starmer has chosen a risky ally on which to place such weight. Chancellor Scholz’s personal poll ratings are catastrophic, with two-thirds of the electorate regarding him as doing a bad job, while the SPD is currently third behind the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Alternative für Deutschland. Unless there is a drastic change in circumstances, the governing coalition of the SPD, the Greens and the Free Democratic Party will endure a drubbing at next year’s Bundestag elections and have little prospect of retaining office.

Scholz’s administration is under particular pressure on defence, one of the very issues on which Starmer wants to concentrate. Only three days after the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Chancellor made a rousing speech to the Bundestag in which he declared that there had been a Zeitenwende, or change of eras, and that his government would reverse decades of cautious defence policy and use a €100 billion fund to increase substantially its military expenditure.

The retreat from the Zeitenwende speech has been precipitate and calamitous, as well as shameful. Scholz managed to reconcile the different elements of his coalition over a proposal to relax Germany’s constitutional debt brake which limits public spending, but to do so he had to defer a number of military commitments. The defence minister, Boris Pistorius, had requested an additional €6.5bn for his department but will receive only €1.2bn, and Germany will only just meet Nato’s minimum requirement of spending 2% of GDP on defence.

In addition, the German government is cutting its financial assistance to Ukraine by half to €4bn, arguing in mitigation that President Zelensky will be able to benefit from $50bn in frozen Russian assets across Europe (though it is unclear when this might become available and Scholz himself admits that it will be ‘technically demanding’).

An almost-impossible burden is being placed on the possibility of a bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany. The Prime Minister may see value in the mood music of ‘resetting’ relationships with Europe, but the EU will not allow its member states to circumvent their communal obligations on trade and borders to create bespoke arrangements with an eager Britain.

Keir Starmer is cosying up to a floundering administration which is cutting back on its international and military commitments. He will have to be careful not to invest too much in his relationship with Olaf Scholz and the current coalition, and should bear in mind that if the CDU leader, Friedrich Merz, becomes Chancellor next year, there is a substantial gap between the two men to be bridged. Merz is a traditional, socially conservative and pro-business politician who is sceptical of achieving carbon neutrality by regulation rather than innovation, and wants to deepen ties between France and Germany. It will take some ingenuity to see a place for the United Kingdom in that dyarchy.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.