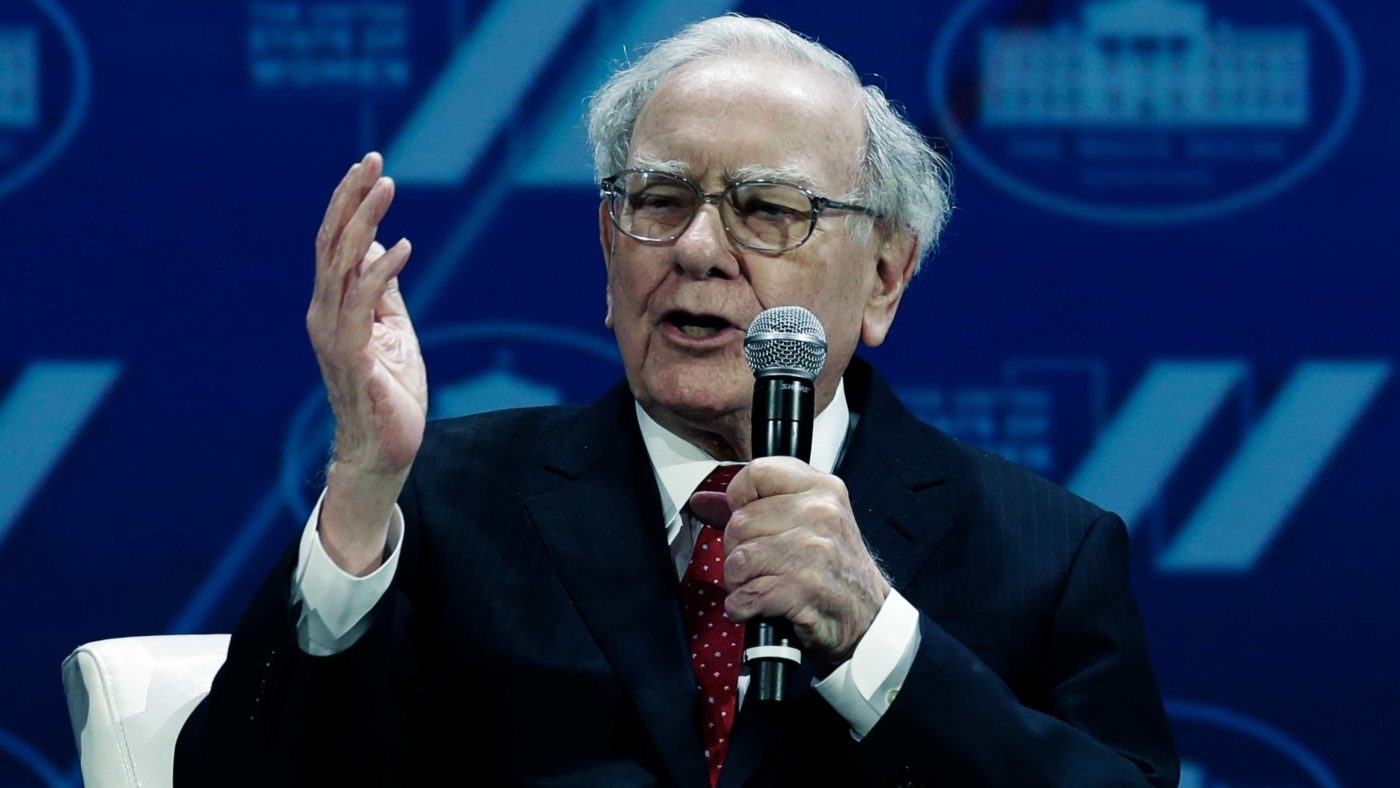

The Guardian has reached for the smelling salts as Warren Buffett tells us all that slashing jobs is just the capitalist way. Yes, it’s that time of year again: Woodstock for capitalists, the Berkshire Hathaway annual general meeting.

The meeting is an opportunity to hear all sorts of folksy wisdom from Buffett and his sidekick Charlie Munger. This year, remarking on how their joint attempt with 3G to take over Kraft Heinz has led to firings, jobs losses and rationalisations, Buffett said that is just how capitalism does it. Businesses strip out costs so as to be able to make things more cheaply and thus boost the profit margins.

One can see why The Guardian is having fainting fits: the oppressed workers being thrown on the scrap heap by the plutocrats.

But Buffett is wrong. This isn’t the capitalist way at all. This is just the way that any and every economy should work. Whether communist, socialist, social democratic or capitalist, all economies will economise on inputs into a process. That is what actually makes us richer.

Buffett’s subsequent point – that “people live better when there is more output per capita” – is right. But that’s not specific to capitalism.

That takes us back to the original economic problem. Human desires and wants are unlimited and yet we only have scarce resources with which to meet them. Economics is the study of how we allocate those scarce resources to meet our wants. And we get the most desires sated by being economical with our use of resources.

To take a very technical example, back when the 80286 Intel processor was still a pretty neat idea the gold plating on its connector pins was some 200 nanometres thick. Today’s much faster processors have plating on pins of perhaps two nanometres.

We are able to make 100 times as many processors from the same amount of that scarce resource. And we know that gold is scarce; that’s why it costs upwards of $1,000 an ounce. Being economical with the gold has made us richer, because we have more processors.

Human labour is also a scarce resource. And being economical with the use of it is the very thing which makes us richer. To flesh out Buffett’s point, if 100 people make 100 widgets, and then we increase productivity so that 100 people make 200 widgets then everyone is richer by one widget a head.

But there’s another much more important sense in which, as Paul Krugman has pointed out, productivity isn’t everything but in the long run it’s pretty much everything.

Imagine a society in which everyone is a subsistence peasant. Give or take a few Kings and priests that was pretty much all of human history before 1750 or so. Then we make agriculture more productive, we raise output per head among those who wander muddy fields.

Suddenly we’re all getting three square meals a day, not the normal human historical experience. But that’s not really what makes us richer here. Today, instead of everyone working in the fields, just 2 per cent of us do so. The other 98 per cent of the population are busing trying to sate some other human desire or want. And thus, we have the labour to run a health service, libraries, ballet companies, vital cat picture websites, manufacturing, ketchup plants and the like.

Being economical with labour is the very thing that makes civilisation itself possible.

Again, this isn’t specific to capitalism. Any economic system worth the name is going to continually strive to reduce inputs into production. And human labour really is just one of those inputs. Being economical with it makes us richer not just by the increased output from those still doing the original process, but by the new and different things the now displaced labour goes on to produce instead.

As to who gets that increased production, a purely capitalist system might indeed see just the plutocrats getting that extra. But that isn’t what actually happens, William Nordhaus has pointed out. The entrepreneurs – for devising a new process which uses different or fewer inputs is the very definition of entrepreneurship – end up with some 3 per cent or so of the value they create. The remaining 97 per cent flows to the rest of us in the form of consumer surplus. And it isn’t capitalism that does that, it’s markets. Markets in which one can spot a new idea being used by another then copy it, improve it, compete with it.

As Jason Furman (formerly Chair of Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers) has pointed out about Walmart, a company famously light on the use of labour and paying for it. Reasonable studies show that the company’s policies lowered retail wages – which is exactly the same thing as caused economy in the use of labour – by some $4.7 billion in the year 2000. A separate estimate of the savings that consumers made from the very existence of Walmart – because their low prices means everyone else has to temper their prices, margins and profits – savings of $263 billion in 2004.

Buffett is correct in that using less of a scarce resource, the same thing as higher output per head or raising the productivity of labour, makes us all potentially richer. It’s even possible that capitalism is the best way of encouraging this. But it is markets and competition which mean that the benefits flow to us out here, not just pile up in the capitalists’ vaults.

This is, though, about more than poking fun at The Guardian. Not enough people realise that using fewer resources to do something makes us richer. And yes, human labour is just such a scarce resource that we wish to economise upon using. Perhaps if people understood this, they’d stop arguing that solar power is better than nuclear because it produces more jobs for the same amount of electricity produced.