There’s a well-worn habit in politics: seize on a big number and offer a simple fix, without fully understanding the system that produced it. Reform UK’s proposal to scrap interest payments on commercial bank reserves, purportedly saving the taxpayer £35 billion a year, is a textbook case. It’s bold, headline-grabbing and superficially appealing. But economically, it’s reckless.

At first glance, the logic seems obvious: commercial banks are earning billions in interest from the Bank of England on their deposits. Why not just stop paying them? Wouldn’t that free up money for public services?

But the monetary plumbing behind this system is far more complex than the populist narrative suggests. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the Bank has controlled interest rates using what’s known as a ‘floor system’. In essence, the Bank creates reserves – via quantitative easing (QE) – and pays interest on those reserves at the official policy rate (known as Bank Rate). This framework ensures short-term market rates remain anchored and allows monetary policy to be transmitted cleanly through the economy.

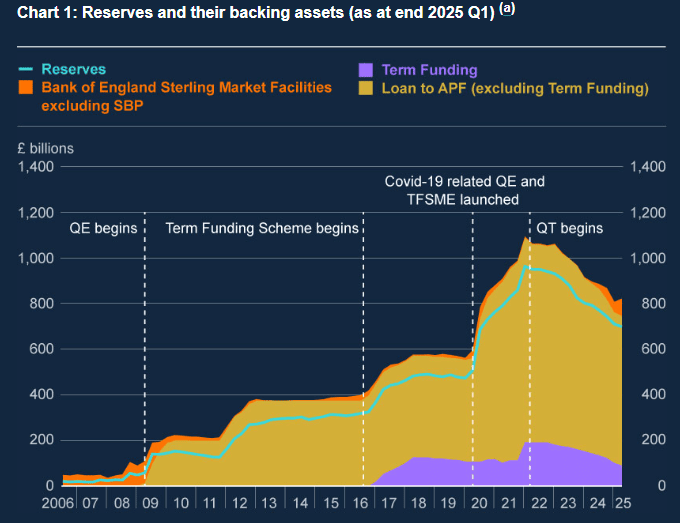

It replaced the pre-crisis ‘corridor’ system, where reserves were scarce, and interest rates were controlled by rationing liquidity to just about meet the banking system’s need for settlement and precautionary balances. In today’s regime, reserves are abundant, and the policy rate is transmitted by remunerating those reserves. It’s not flashy, but it’s essential. The current stock of reserves – about £700bn – is a legacy of QE and monetary support up to and through the pandemic. At its peak in early 2022, reserves hit £979bn.

.

Reserves are not ‘freebies’ to banks. They are liabilities created to fund the Bank’s asset purchases. To remove the interest on reserves would be to switch off the mechanism that links the Bank Rate to real-world lending and borrowing costs. It’s the equivalent of cutting power to the grid and expecting the lights to stay on.

This isn’t just theoretical. As Andrew Hauser, the Bank’s former Executive Director for Markets, explained in a 2019 speech, the floor system is essential not just for rate control, but for financial stability. Banks use reserves to meet payments, manage liquidity stress and comply with post-financial crisis regulatory obligations. Undermining the return on reserves would likely force the Bank back into daily firefighting – exactly what it has spent the last decade trying to avoid.

As Toby Nangle put it in a recent FT Alphaville column:

… if the Bank stopped paying interest on all reserves… interest rates would collapse to zero… the only reason why overnight rates pay any attention [to Bank Rate] is that under the current set-up the Bank of England pays [that rate] on reserves. In doing so they set a floor below which no bank would lend.

And yet, the optics are politically potent. Critics such as Liam Halligan, who wrote in The Telegraph this week, argue the current system looks overly generous to banks. That view is not without public resonance. In an era of stretched public finances and elevated interest rates, the idea of cutting back on ‘handouts’ to the City plays well. But these payments are not arbitrary. They reflect the necessary cost of reasserting monetary control after inflation hit 11.1% in October 2022.

Yes, the Bank is now paying out more – because Bank Rate has risen from near-zero to 5.25% in two years. And currently sits at 4.25%. But abolishing interest on reserves wouldn’t remove the need for high rates. It would simply force the Bank to deploy less efficient tools to maintain control, likely increasing volatility and raising costs elsewhere in the system.

Some economists have suggested a middle ground: tiered remuneration, as used by the European Central Bank. Under this approach, the central bank pays the full policy rate only on a portion of reserves and less (or nothing) on the remainder. This is effectively a tax on banking activity. This does reduce the fiscal burden. But it was designed for conditions of low inflation and excess savings. To implement tiering in the UK today would risk tightening monetary conditions unintentionally, potentially amplifying stress in financial markets at exactly the wrong moment.

There’s also a deeper problem with Reform’s proposal: it conflates fiscal and monetary policy. Richard Tice, Reform’s deputy leader and likely Chancellor in a future Reform government, claims ending these payments would free up ‘huge sums’ for public services. But this misunderstands the Bank’s function. Interest on reserves is not a Treasury handout – it’s a tool for controlling inflation. Politicising it would risk undermining the Bank’s operational independence and credibility.

That said, the Bank is not blind to these concerns. As part of its quantitative tightening programme, it is already shrinking its balance sheet. And in recognition of the need for a more sustainable operating framework, it has introduced the Preferred Minimum Range of Reserves – an estimate of how much liquidity the banking system needs to function efficiently. That range is currently £345-490bn (but nobody really knows the right amount). While we’re still well above that level, as reserves fall toward it, the case for recalibrating the system – including through tiering – will become stronger.

In the meantime, interest on reserves is not a ‘giveaway’. It’s the price of maintaining a functioning transmission mechanism in a world of large central bank balance sheets. Cut it without a coherent replacement and you risk chaos in overnight markets, weakened monetary control, and a potential credibility crisis.

But for all its flaws, Reform’s proposal has done one thing right: it has forced a necessary debate. For too long, the Bank of England’s operating framework has been treated as a closed issue – too technical for public discussion. But when tens of billions of pounds are at stake, it becomes a legitimate political concern.

Scrutiny is healthy. Monetary policy shouldn’t be off-limits simply because it’s complicated. But that scrutiny must be rooted in understanding, not opportunism. Reform UK may be wrong on the mechanics, but they’ve asked the right question: is the Bank’s current approach still serving the public interest?

That question matters – especially in a world of higher interest rates, ballooning public debt and persistent economic uncertainty.

And if the aim is to raise money from the banking sector, let’s be honest about it. A targeted tax on bank profits would be simpler, more transparent – and far less likely to destabilise the financial system.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.