So, there we have it. Runcorn & Helsby 2025 joins the likes of Crosby 1981 and Orpington 1962 in the list of seismic by-election victories by a party outside the ‘big two’.

As so often in such cases, pollsters and data nerds will be understandably vexed by the weight given to the result, given its closeness. Had Labour instead held the seat by six votes, rather than lost it, it would tell us nothing different about the state of public opinion – but would undoubtedly shift the narrative spun from the result.

But a close victory for Reform UK is a different story to a close defeat, and humans are storytelling creatures. For that reason, political narratives do end up having a real impact.

Sometimes prophecies become self-fulfilling, as voters and politicians alike shift their behaviour. On other occasions they merely help unpopular parties stick their heads in the sand, as did the Conservatives in 2023 when a narrow victory at the Uxbridge & South Ruislip by-election helped the party delude itself about an absolutely terrible night.

Today, the Tories are clutching at a different comfort blanket: that these elections are simply too soon to be considered a fair test of Kemi Badenoch and her new direction, and that the results were always going to be dire given the woefully unpromising playing field.

Like all the best self-deceptions, there are threads of truth in that tapestry. The last time this particular map was fought was in 2021, at the apex of Boris Johnson’s popularity. As such it was always going to be all but impossible to replicate William Hague’s achievement in 1998, when he managed to pick up hundreds of councillors just twelve months after what was, until last year, the party’s annus horribilis.

It is also unlikely that even a leader of historic ability would have been able to put the Conservatives back on the front foot so swiftly after an historic rout like last July’s, especially when so many of the areas voting yesterday had booted the Tories out less than twelve months ago.

Yet none of this should blind the Conservatives to the existential danger they’re in. According to pollsters to whom I’ve spoken, what’s unfolded so far is at the very top of their expectations for Reform UK’s performance. With the possible exception of the Cambridgeshire mayoralty – at the time of writing a possible gain from Labour – there are few, if any, points of light for His Majesty’s Official Opposition.

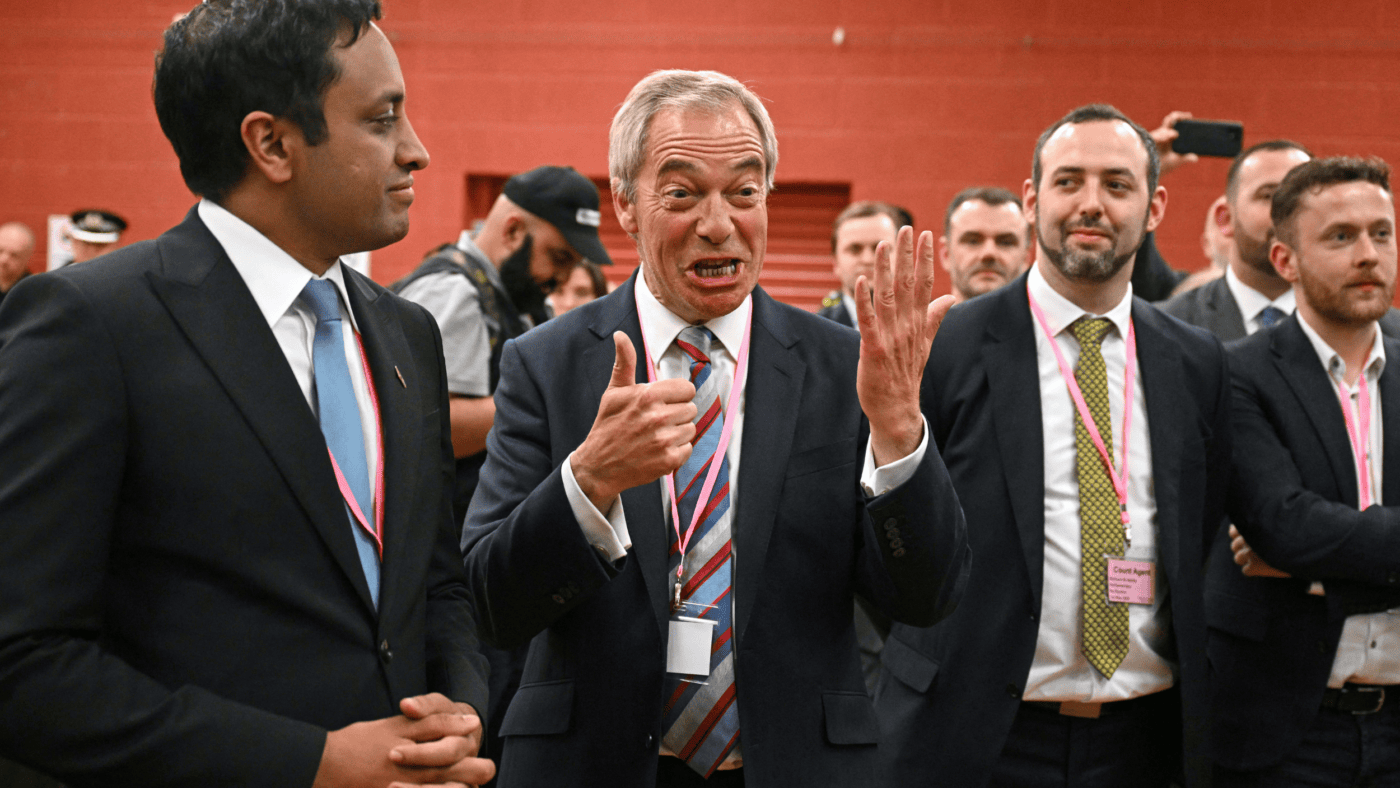

Even if Nigel Farage never becomes prime minister, on these numbers Reform could quite plausibly be on track to establish itself as a right-wing version of the Liberal Democrats, and that could make life very complicated for whoever is Tory leader.

After the previous Conservative rout in 1997, Paddy Ashdown led the newly-minted Lib Dems on an extremely successful campaign through former Tory strongholds in rural and suburban England, especially in the South West. Once those MPs became entrenched, it proved almost impossible for the Conservatives to pry them out, unless the local MP retired and their personal vote unwound.

It took until 2015, when Nick Clegg had taken his party into national government, for the protest-vote bubble to burst.

Farage could pull off a similar feat. Nearly all Reform’s second places at last year’s general election were against Labour, so he has the advantage of facing off against an increasingly unpopular incumbent government. Moreover, many of them had previously voted Conservative (often for the first time) in 2019, so they have broken the always-voted-Labour spell and demonstrated willingness to vote for a party of the Right.

If it can build on these results – and that remains for now a big ‘if’ – then the Tories’ electoral map gets much more complicated. Hague had to grapple with being wiped out in Scotland; his successors may need to reckon with the loss of Wales and the Red Wall as well.

Worse still, trying to take the fight to Farage in those areas will pull the Conservatives in a different direction to that likely required by their current battleground, which mainly faces Labour or Lib Dem incumbents in the party’s traditional, southern heartlands – and may expose sitting MPs on narrow majorities to well-organised local campaigns by the Lib Dems or the Greens.

Defenders of the current leadership may fairly ask if Robert Jenrick has yet proved himself the answer to a question this complicated. But his supporters might counter that the real question, with only 121 MPs, is simply whether he’s the best answer the party currently has.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.