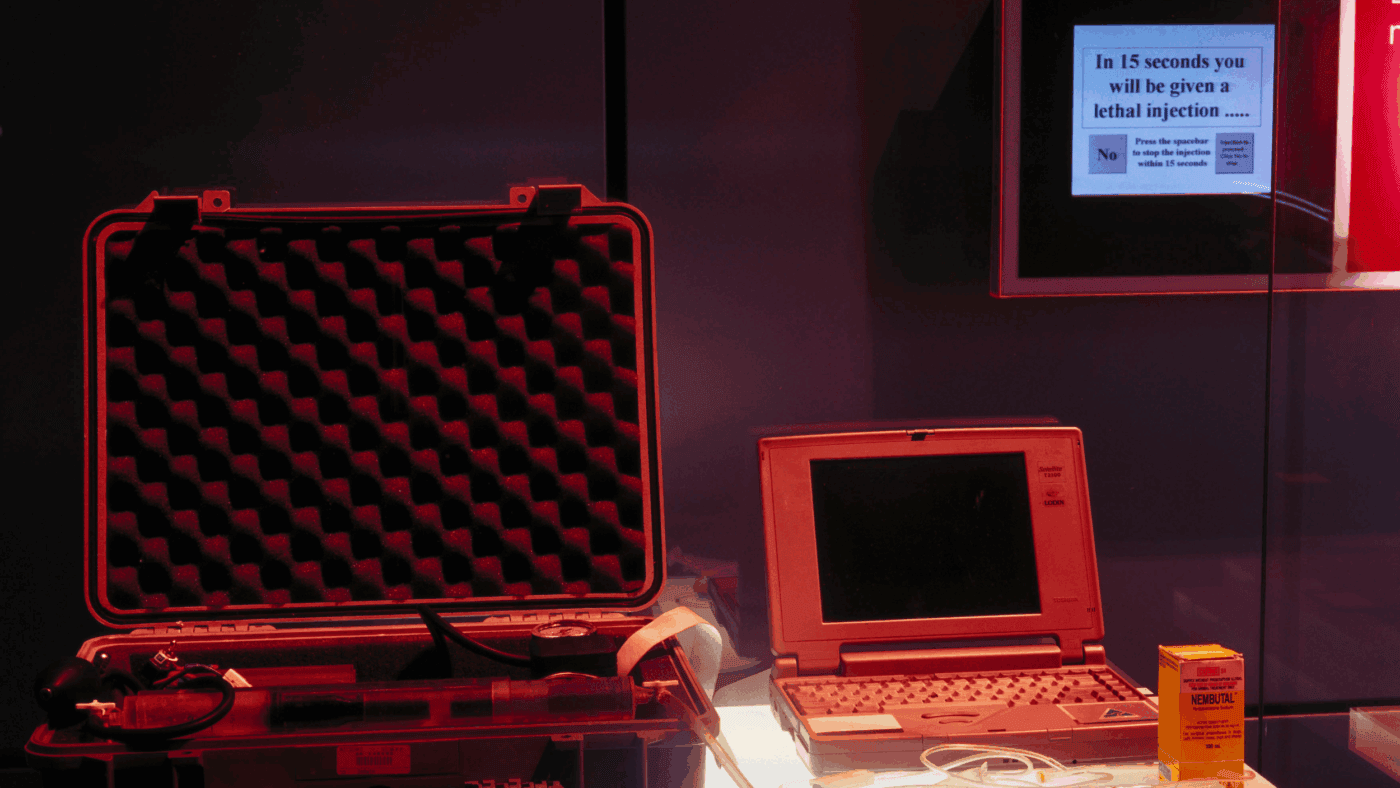

In 1995, when assisted dying was briefly legalised in the Northern Territories of Australia, Dr Philip Nitschke created a suicide machine named ‘Deliverance’ by linking up his laptop to a syringe of deadly chemicals.

This ‘suicide machine’ became a source of immediate controversy when displayed as an icon of contemporary medicine at the Science Museum in South Kensington twenty-five years ago.

Purchased to star in a £50 million expansion funded by the Wellcome Trust, Deliverance not only proved a star object but materialised very real fears into the public realm that resonate today.

Nitschke’s machine asked its users 22 questions – the last of which was ‘if you press “YES” you will cause a lethal injection to be given in 30 seconds and will die’ – before killing the patient.

A prototype allowed users to choose from a range of music CDs before flashing the message ‘Goodbye and good luck’.

Undeniably, the museum had bought a ‘unique, historic object’ (as the then curator put it), but using a machine that had killed four people as a talking point generated continual anxiety, and for good reason.

Immediately, the museum was criticised for teaching children ‘the science of self-destruction’.

Beyond the ghoulish details and media outrage, the deeper sources of this uneasiness remain instructive as Kim Leadbeater’s Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill passed its final Commons vote today.

When William Munk published his seminal textbook ‘Euthanasia’ in 1867 he was using the term in the classical sense of ‘a calm and easy death’, not the contemporary conception of ‘euthanasia’ as a type of mercy killing.

By contrast, since described by Newsweek as the ‘Elon Musk of Euthanasia’, Nitschke’s commitment to assisted dying has been a mission pursued with a frenzied intensity. He followed Deliverance with ‘the Coma machine’, ‘the Exit bag’ and ‘Sarco’, a suicide pod that could be 3D printed at home. After euthanasia was legalised in the Netherlands, Nitschke toyed with hosting a floating euthanasia clinic on a Dutch-registered ship anchored off the coast of the UK.

A nose for publicity and a hunger for notoriety doubtless drove much of this, but wheezes like Deliverance also had a practical purpose.

While assisted dying gives clinical staff permission to kill their patients, doctors and nurses must protect themselves from future accusations of murder or manslaughter.

It is one thing for a doctor to accept that a patient no longer wants to be treated, but by creating the right to a shorter death, assisted dying shifts significant new professional, legal and moral demands onto medical practitioners.

Assisted dying not only entailed that Deliverance worked as an efficient ‘suicide machine’ but an efficient ‘suicide machine’ that protected the medical staff who administered it from future legal liability.

Even Nitschke admitted that his first Deliverance patient spent ‘his last hour talking me up, raising my spirits.’

After the patient had died, he continued, his wife gave Nitschke the feeling ‘that she wanted me to leave’.

While proponents of assisted dying then (as today) argued for the right to die with dignity, Deliverance evidenced a reality that was likely to be both more banal and considerably bleaker. Not least the realisation that it is not possible to enshrine the right for assisted dying without opening the door to coerced, involuntary deaths.

As part of a new push to centre debates in contemporary science and medicine, the museum subsequently brought Nitschke to an invite-only discussion foregrounding ethics and safeguards.

But ordinary visitors gazing at ‘Deliverance’ could see that the future would not be high-powered philosophical debates chaired by Sir Stephen Tumim (as they were at the opening of the gallery) but IT-enforced compliance, box-ticking and endless requests for consent.

The ‘22 questions to death’ that Deliverance’s patients had to click through included ‘Is the patient of sound mind?’, ‘Has the patient completed a certificate of request?’ and ‘Are you aware that if you go ahead to the last screen and press the “YES” button you will be given a lethal dose of medication and die? “YES” or “NO”?’

Any assumption that assisted dying would prove heroically ‘rational’ were quickly dispelled.

For his part, Nitschke once said that he would choose to die like a dog, by taking Nembutal, the barbiturate used by vets to put down animals. No illusions, perhaps, but to most ears this didn’t sound particularly like dying with dignity. Since then suicide pills – far from painless, and often not particularly quick – have become the default mode of killing where euthanasia has been legalised.

Deliverance served as a tangible reminder that while it is possible to make an ethical defence of assisted dying in the abstract, sooner or later you are faced with the far less palatable problems of praxis.

As the Leadbetter Bill now makes its way into the Lords, today’s politicians seem less unnerved than the museum visitors of 25 years ago, who had to confront the reality that there is, in fact, no painless way to do this.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.