What has happened to Iceland? The failed economy which crashed in 2008, taking a chunk of Britain’s tax funds with it, had to be bailed out with an IMF loan of $2.1 billion. That same IMF now ranks the country as 16th in terms of GDP per capita, ahead of Germany, France, and the UK. Iceland beats the UK on the Legatum Institute’s Prosperity Index too, coming in 11th place, with strong marks not only for safety and personal freedom, but also for Entrepreneurship & Opportunity. The unemployment rate is currently just 4.6%, and Forbes writer Brent Beshore called the country “an entrepreneurial powerhouse” in July. It has been rated as one of the happiest countries in the world, and according the Telegraph:

“Offering a relatively low income tax, free health care and post-secondary education to its citizens, the island country has also been rated to be the most peaceful nation on Earth on the Global Peace Index, endorsed by pacifists such as Kofi Annan, the Dalai Lama, and archbishop Desmond Tutu.”

With this in mind, maybe we should all be packing up and moving to Iceland. Or maybe not, since capital controls would make it almost impossible to move back. If you want to buy foreign currency in Iceland, say for a holiday in New York, you must present proof to your bank that you are travelling to another country by showing your plane ticket. Conversely, this makes it extremely difficult for foreign tourists to buy krona for their holidays, as I discovered the day before my recent trip to Reykjavik when the company I had ordered currency from called to tell me they didn’t have access to it.

Capital controls which were intended to last weeks, months at the most, have now been in place for 6 years. About $5.9 billion worth of assets are currently locked up in the form Icelandic krona, and no one knows when the controls will end. In July 2014, the Icelandic government hired experts to advise on how to remove them, and a recent poll from Bloomberg suggests the controls will be over by the end of the current government’s term in 2017. But the fact is, nobody knows. And while the controls prevented a run on the krona in 2008, they have also discouraged investment in Iceland, and kept exporter earnings out of the country, ensuring the currency stayed weak.

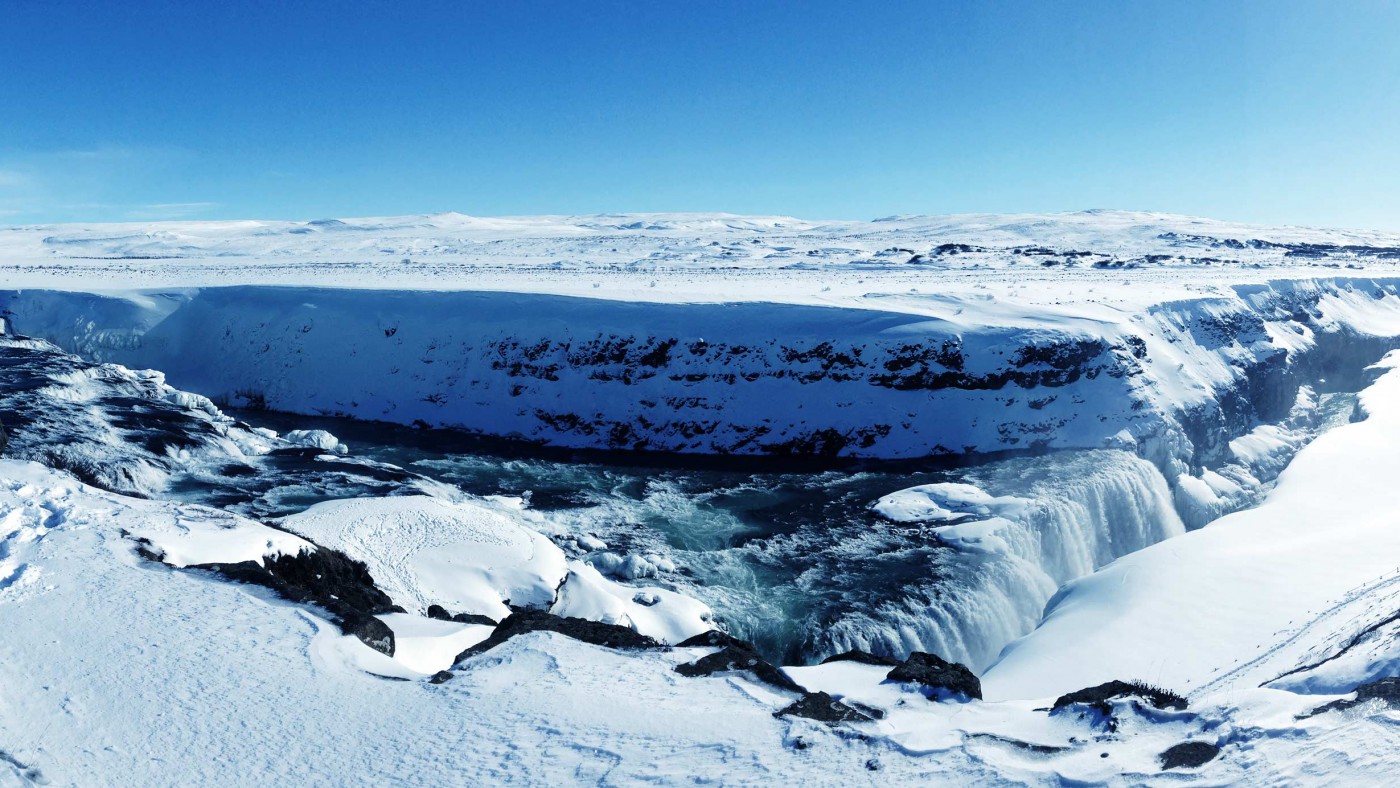

First-rate enterprise, damaged investment opportunities. A social justice paradise with draconian capital controls. Iceland’s economy is truly one which resembles its landscape: volcanic, inconsistent, and full of surprises.

These contradictions are perhaps not a bug of the Icelandic model, but a feature. In 2011, Iceland shocked the financial world by choosing not to bail out its banks. When its three largest banks crashed and defaulted on $85 billion, the government denied that this was public debt and refused to back it up with taxpayer funds. Since many of the accounts were owned by ordinary British and Dutch savers, the UK and Netherlands were forced to offer compensation – a fact which still causes contention. The UK even used anti-terrorism laws to freeze Icelandic assets in response. (On a more humorous note, after the volcano Eyjafjallajökull erupted in 2010, spreading an ash cloud over Northern Europe and disrupting over 95,000 flights, a facebook group was founded entitled Dear Iceland, we said send cash not ash.)

Many within Iceland feared this would make their country an economic pariah and pushed for staying on good terms with Europe’s governments. So why did the government behave so differently from Ireland and Portugal when faced with the same crisis? The answer may lie with a quote from current Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíd Gunnlaugsson in one of his first speeches after winning the 2013 election:

“Icelanders, as descendants of the Vikings, are highly individualistic and have difficulty putting up with authorities, let alone oppression.”

Iceland’s very existence is a libertarian dream. In the 9th century, Viking explorers from Scandinavia left their homeland. Common tradition claims this was due to the dictatorial rule of the Norwegian King, who demanded high taxes to fund his many wars. Iceland’s founders are fiercely strong-minded individuals who resent being told what to do. In 874, the assembly of the Icelandic Commonwealth was founded, known as the Althing. This parliament, based in Þingvellir on the continental rift between the North American and Eurasian plates, observed no central authority, but was a cross between a proto-democracy and an oligarchy, with leadership positions that could be traded, and national assemblies open to all. The Althing is the oldest parliamentary institution still in existence today.

Fast-forward 12 centuries, and Iceland’s solution for dealing with its economy’s collapse makes a lot more sense. After protests in 2008 and 2009, it was clear that Icelandic constitution needed a rewrite, and in the style of the early Viking settlers, updated for the 21st century, the government decided to crowd-source it.

A random draw selected 950 people to form a national committee, who proposed key provisions needed in the new constitution. 25 individuals were then elected from a separate group of candidates, all nominated by friends and colleagues, none of whom could be politicians. These 25, including a farmer, a pastor and a radio presenter, formed a constituent assembly, and began rewriting the constitution based on the recommendations of the earlier consultation. They opened up the process to the public by inviting people to comment on drafts via social media: “In total, the crowdsourcing moment generated about 3,600 comments for a total of 360 suggestions.” A referendum on the new constitution was held in 2012, where it passed by 67%.

It would be wonderful to end by saying that this form of intensely direct democracy triumphed and that the crowd-sourced constitution, which included provisions such as equal voting rights and limiting executive powers, is now in place. But that is not what happened. A series of obstacles, including weak parliamentary support and fierce opposition from the Independence Party and the Progressives, delayed passing a bill that would implement the constitution before the parliamentary recess and the election in April 2013. The incumbent government fell, and the Independent-Progressive coalition which emerged, led by Gunnlaugsson, has so far made no move to resume any work on the constitution.

And so we return, once more, to Iceland’s inherent contradictions. No other Western democracy would decide to hand the rewriting of its constitution over to the general public after a major crisis, spend three years drafting a document using social media, then fail to implement it and allow it to fade from public awareness after two years. This is a land founded by Vikings, now the most peaceful place in the world, where money cannot be taken out of the country, which is a hotbed for entrepreneurs, where failed banks were nationalised, where politicians gave constitutional power to the people then took it back again, and which most people would struggle to find on a map.

For a country where boiling water bubbles out of glaciers, what else would you expect?