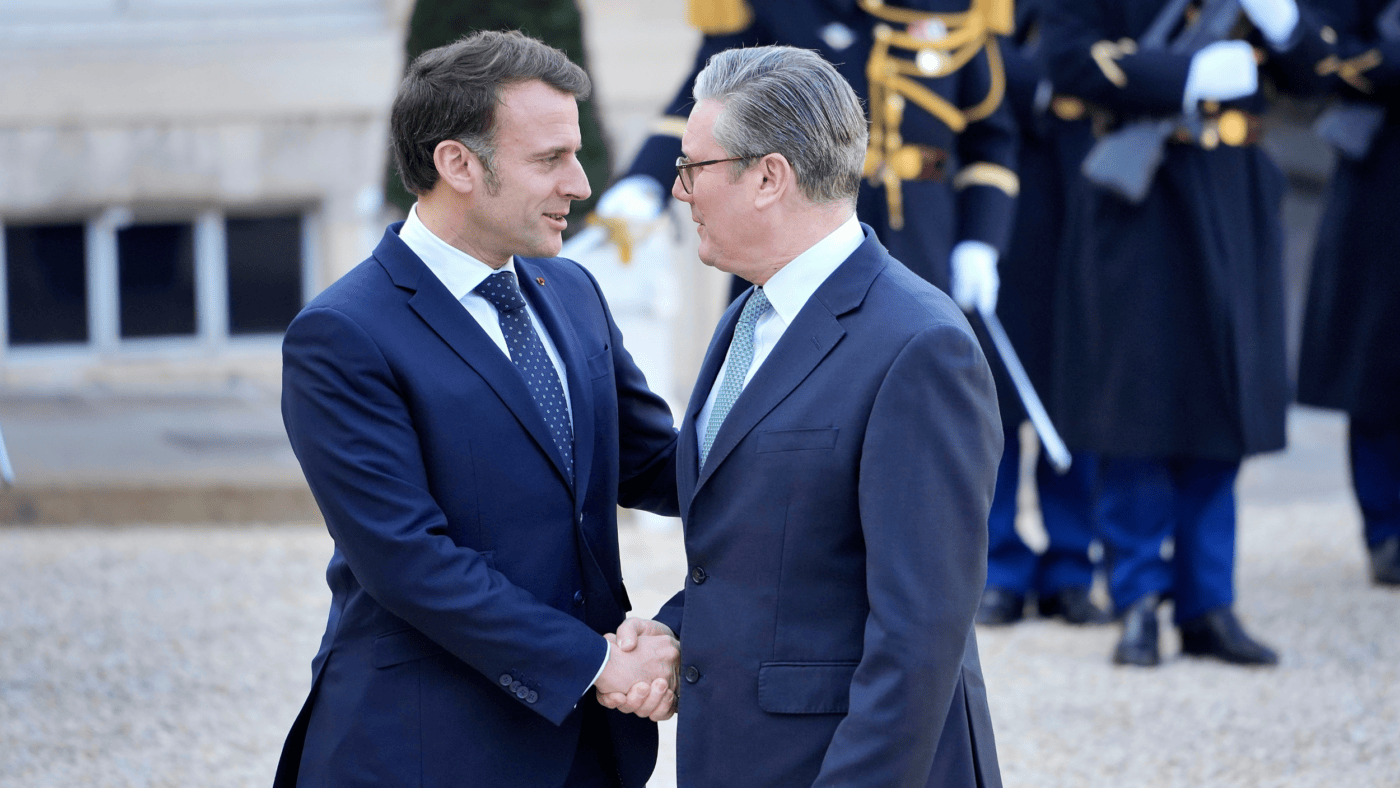

If you need to hold a summit, Paris comes highly recommended: since the peace conference which produced the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, there have been at least four similar major meetings in the French capital. It was natural enough, then, that European leaders responded to President Emmanuel Macron’s invitation and converged on Paris on Monday to discuss Ukraine.

This truly was an ‘emergency’ summit. It was announced on Saturday, a rapid response to recent events: President Donald Trump revealed that he had spoken to Vladimir Putin and would meet the Russian leader to discuss ending the war in Ukraine. Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the president of the country invaded, was informed of the conversation afterwards.

Despite the short notice, the apparent agenda of the summit varied within 48 hours. Initially, there was a strong sense that Europe had to respond to the prospect of America scaling down its commitment to its allies and withdrawing much of its resources. Yet by Monday afternoon, somehow, conversations focused on peacekeeping and the implementation of a notional settlement between Ukraine and Russia, before negotiations have even begun.

Monday’s summit produced no groundbreaking statements or major changes in policy. Essentially, the representatives of Europe’s governments agreed that they should ‘do more’ on defence, that Ukraine should be involved in any negotiations over its future and that the security of Ukraine had implications for the whole continent. Keir Starmer, perhaps rehearsing his lines before he meets President Trump in the White House next week, said that he was willing to consider contributing British military personnel to a peacekeeping force.

The truth is that the UK has little capacity to deploy substantial forces. Putin is unlikely to countenance a Nato-led peacekeeping effort anyway, but Zelenskyy has indicated any force would need to be 200,000-strong. The British Army would currently be at full stretch to generate a single brigade combat team of 3,000. Meanwhile Poland’s prime minister Donald Tusk has ruled out contributing peacekeepers, and the German government (facing an election on Sunday) is non-committal. There is an air of unreality.

At last weekend’s Munich Security Conference, President Zelenskyy, who must feel a little like an extra in his own country’s drama at the moment, argued that the solution to American disengagement was the creation of a European armed forces.

‘We can’t rule out the possibility that America might say no to Europe on an issue that threatens it. Many, many leaders have talked about Europe that needs its own military – an army of Europe.’

A military alliance bringing together the assets of the majority of European countries, with tried and tested command, control and planning capabilities, and an established mechanism for political decision-making: imagine how powerful that would be.

Of course, it already exists in the form of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. Even better, Nato seamlessly integrates the United States and Canada too.

Zelenskyy’s plea for ‘an army of Europe’ will be taken up by some as an opportunity to expand the European Union’s role in defence. This is a long-standing ambition of many in the EU, an obvious gap in the organisation’s trajectory towards ‘ever closer union’, the first objective named in the foundational Treaty of Rome in 1957.

The Treaty on European Union includes as an EU competence a common security and defence policy, including Permanent Structured Cooperation between member states, and a European Defence Agency; ‘common defence’ is stated as an ambition. In addition, when Commission President Ursula von der Leyen established her second College of Commissioners last year, she created a new separate portfolio for defence and space. In legal terms, however, defence and security remains a national competence.

A unified European armed forces would be catastrophic. Although the Treaty on European Union has explicit provisions under Article 42 ‘not [to] prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy’ of Nato member states, imagining the alliance functioning alongside a common EU defence force and integrated military structures makes the duplication obvious. You have one or the other.

It could be argued that this makes a virtue out of a necessity. If the United States is shifting its strategic focus to the Pacific and is no longer wholly committed to the collective security provision of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, then the EU is surely the obvious alternative mechanism to coordinate Europe’s defence.

This is flawed for a number of reasons. Firstly, the EU and Nato are not analogous organisations: Nato is a military alliance providing mutual defence, while the EU is a sprawling supranational body with a substantial permanent bureaucracy and elaborate decision-making processes.

Second, the UK is no longer an EU member, but spends more on defence than any EU member state except Germany, has armed forces bigger than all but half a dozen EU countries and maintains an independent nuclear deterrent. How would the UK be involved in a primarily EU-run military organisation?

Fundamentally, however, this comes back to Nato. To use the alliance rather than the EU as a vehicle for defence coordination excludes only Austria, Cyprus, Ireland and Malta, none of which are significant military powers. Nato’s Military Committee, International Military Staff and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe are experienced and effective institutions. And there is nothing to prevent some Nato member states engaging in coordinated military activity without contributions from all; America could simply stand aside.

On the other hand, if the European members of Nato suddenly embrace the EU as an umbrella organisation, and the alliance is left to wither, then the United States will conclude that Europe is going its own way. Instead of adapting Nato for new circumstances, we would be abandoning it to create a huge multinational armed forces with different traditions, doctrines, structures, equipment and recruitment, which will be one arm of a political entity looking ever more like a state.

If anyone wonders how a fractured, polyglot, multi-ethnic army works, I refer you to the Imperial and Royal Army of Austria-Hungary in 1918. It did not end well.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.