Over the last few weeks, nutrient neutrality has become one of the hottest topics in Westminster. Now, at least, Labour have shown their hand – and it’s fairly depressing stuff.

Writing in The Times today, in their first announcement in their new briefs, Angela Rayner and Steve Reed said that Labour will be voting against the Government’s proposed reforms and putting forward its own amendment. Their aim is very clearly to position themselves as the grown-ups in the room, saying yes we need housing, yes this is a problem, but unlike the Tories we’ll also protect the environment. In other words, have cake, eat cake.

In some ways, this is actually pretty encouraging. Unlike many people on Twitter, Labour aren’t pretending that nutrient neutrality isn’t a problem, or that it isn’t holding up the building of desperately needed housing. They accept something needs to be done.

The problem is that for all their talk of prioritising housing, the opposition seem unwilling to make the tough choices that would involve. Indeed, the main effect of their plans would be to replace a handout to housebuilders with a handout to landowners – while getting many fewer houses built.

But the problems start when you get into the detail. First up, there’s lots of stuff in the piece about sewage spills being at a record high, thanks to the Tories neglecting enforcement and monitoring. But this just absolutely isn’t true.

You can read my summary of nutrient neutrality here – and indeed my Sunday Times column on the wider issues here – but the gist of it is that new housebuilding results in more poos from loos, which increases phosphate levels in ecologically vulnerable rivers and conservation sites. But as per a 2018 ECJ ruling, that can’t happen – no project near those sites can increase net pollution at all. Hence Natural England pausing housebuilding nearby, and trying to set up methods of offsetting and mitigating the phosphate emissions.

In their article, Rayner and Reed couch this as part of a wider Tory failure on water quality. They write that the Tories ‘recklessly slashed enforcement and monitoring of the water companies that now routinely pump toxic raw sewage into our rivers, lakes and seas. The country is suffering from the highest levels of illegal discharges on record.’

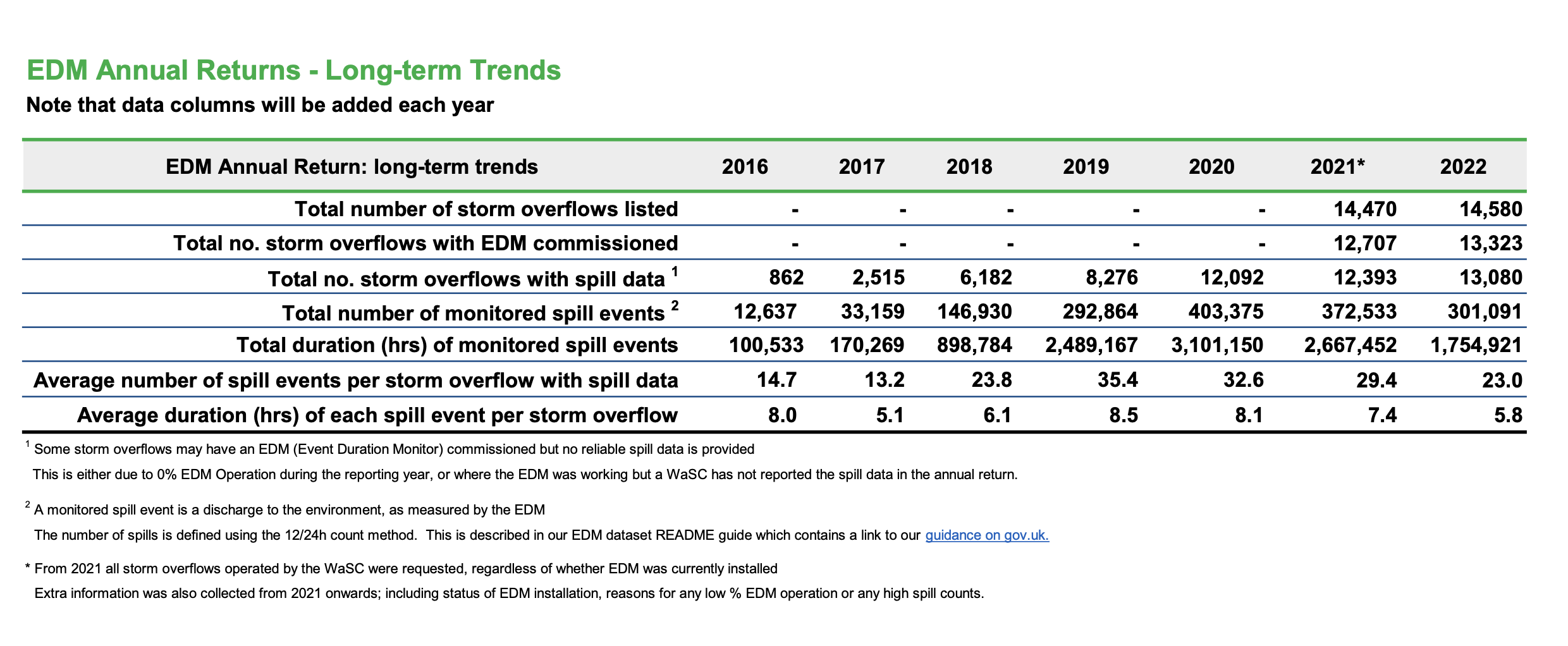

It’s a bad sign for the rest of their argument that this claim simply isn’t true. Environment Agency figures show that spills have come down sharply, although admittedly this was assisted in the latest figures by a drier than usual summer. Moreover, we only know the extent of the problem because of the massive investment in monitoring under, yes, the Tories.

By next year, in fact, we will have monitoring on every outflow in England, up from more than 90% now. That’s compared to Scotland, where just 3.4% of outflows are monitored. Indeed, most of Europe has literally no idea how much shit is going into its rivers.

On nutrient neutrality itself, the core of Labour’s argument is that there is an existing mitigation system that is working perfectly well, but the reckless government have decided to rip it up and weaken environmental protections in the process.

But again, that just isn’t true. The Local Government Association has explicitly said in its planning advice: ‘As a sector we are not currently able to rely confidently on a set of mitigation measures’. Meanwhile the District Councils Network issued an ecstatic press release when the changes were announced, saying that the previous guidance had led to a moratorium on housebuilding, creating ‘severe local difficulties without any meaningful environmental benefit’.

It’s also extremely arguable whether the planned reforms do weaken environmental protections. Two experienced legal experts have examined such claims on these pages, with Dr Ashley Bowes describing them as ‘premature and over-confident’, and Christopher Boyle KC saying that idea that developers are going to fill our rivers with poo ‘are just that’.

There are various other arguments to make here. Phosphate from extra toilets is a tiny part of overall water pollution. Most people using those loos will already live in the area, because people tend to move to homes near where they already live. This isn’t reflected in Natural England’s nutrient calculator, which assumes that every new house will add to the local population. (Fixing that is an obvious quick win, whatever happens with the Government’s reforms.)

Builders already pay infrastructure charges to water companies for new connections. Big developments now have to deliver net biodiversity gain, and will soon have to have Sustainable Draining Systems. And crucially, the government is ordering water firms to strip out phosphates by 2030. Indeed, that is the key proposal that has the RSPB et al so upset – it is telling councils to basically assume these improvements will happen, so they don’t need to apply current pollution standards to the new housing that’s going to be built in the intervening period.

And as I’ve pointed out ad nauseam, the government is also promising to spend more to reduce pollutants than would have been raked in via individual mitigation schemes. So there will be no increase in pollution and no weakening of standards.

In short, the idea that the government is saying ‘build houses, pollute rivers, all fine with us!’ is utter nonsense.

But let’s see what Labour are proposing instead.

Well, Rayner and Reed are actually right that since nutrient neutrality has become a thing, a mitigation market has emerged. The problem is that it’s desperately clunky. At the moment, housebuilders will pay approx £6-9k per household to ‘mitigate’ the extra pollutants from new housing. That means buying a nutrient credit. This is generally spent to create a new woodland or wetland to offset the pollution. That sounds simple. But there are many, many complications.

First, £6k-9k per house is a lot of money. Most people think builders make obscene profits. But it’s a big chunk of their margins. So maybe that house doesn’t get built. Or maybe it means lower contributions to local infrastructure, or a smaller amount of affordable housing, to make the numbers add up. (Again, see the district councils’ statement.) And of course the ‘evil housebuilders’ includes housing associations providing affordable housing, whose projects have also been held up.

Just as importantly, the mitigation system isn’t actually part of the planning process. Builders email Natural England asking for a credit. If successful, they pay 10% upfront and the rest when they get planning permission, which needs to be within 36 weeks. (You can find the guidance here.)

This obviously adds another layer of complexity to the system. It also adds uncertainty – because you’re having to negotiate with two separate bits of government. And it demands that you pay a large bill for mitigation before you’ve even started to build, increasing your capital costs.

Labour are saying we could use ‘Grampian conditions’ – that is build the houses, but only hand over the keys once Natural England confirms neutrality has been achieved. This sounds reasonable. But it actually means you’re committing huge amounts of capital to build something that you then may or may not be able to sell. Which is economically nonsensical. You need to know you’re OK when you start building.

Of course, no one will weep for the builders. But this is also bad for councils. Having gone to all the effort of getting local plans in place, and finding some land where building is permitted, they’re now having that land yanked out of their hands until Natural England is happy.

They’ll have to find more land to replace it, wrecking local plans and upsetting residents. They may get less money to pay for other infrastructure. And they will have to devote a load more time to these issues when planning departments are desperately under-resourced. (Again, see the District Council Network statement.)

Finally, the claim that there are actually plenty of mitigation credits in place and that the market is already working perfectly is nonsense, at least according to everyone I’ve spoken to who’s trying to build houses. There may be enough overall, but not in the areas where most of the houses are being delayed, which is what matters.

So who is the current mitigation system good for? Well, it’s very good for the environmental consultancies that sell the credits. But it’s even better for landowners, who get to rake in very large amounts of cash for creating the woodlands and wetlands mentioned above. (And I’m told this includes some of the NGOs protesting against this so vigorously.)

Of course, woodland and wetland are vital. But you can only create them using existing land – including farmland. That may be good for the rivers, not so much for food security. (Though of course nitrogen run-off from fertiliser is a much bigger contributor to water pollution than new-build housing.)

Ever since the government made this announcement, I’ve been called all the names under the sun for trying to explain why it made sense. You may not agree with what I’ve said above – you may feel that environmental protection should be absolute. But you can surely see that the government is not recklessly trying to destroy the environment in its desperation to build more homes (a desperation not exactly evident in its other policies) but trying to manage complex trade-offs.

I am genuinely glad that Labour are promising to tackle this issue. But it seems like their plan effectively just maintains the status quo, including all the uncertainty and delay – meaning no more housebuilding in these areas any time soon.

And the fact that they are pretending that there is some perfect, painless form of triangulation that can miraculously keep everyone happy – and that the foolish government are foolish fools for not realising this – does not fill me with confidence.

In the meantime, I very much hope the Lords ignore the hysteria and vote through the Government’s plans. Because we really, really, really need more houses, and this helps deliver them while still protecting the environment. Really.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.