Britain will need a new immigration system after we leave the EU. The debate about what that system looks like should start now – and may be less fractious than many might expect.

New research published this week by British Future finds that when the public is engaged more fully with the choices we will need to make on immigration after Brexit, there is plenty of common ground on which people can agree, regardless of their party political affiliation or whether they supported Leave or Remain.

Changes to our immigration system may not take effect straight away in March 2019. A transition period, during which trade and migration arrangements would remain relatively unchanged, would make sense as a way of lessening the shock to businesses who depend on EU citizens to fill skills and labour gaps. But a transition deal cannot be an excuse to delay the changes to Britain’s immigration policy that, as the referendum demonstrated, many people support.

Deciding sooner rather than later what immigration system will be in place after Britain leaves the EU would reassure those concerned that a transition might be used to cling on to EU membership indefinitely. But it would also offer clarity to businesses too. They can only prepare for a new immigration regime once they know what it is going to look like. Kicking the can down the road and delaying that debate because of a transitional deal doesn’t avoid a “cliff-edge”. It just moves it back a couple of years.

While a new, post-Brexit immigration regime would need to work for business, it will also require political and public consent. At first glance, that looks like an unenviable task: Britain’s noisy and polarised immigration debate seems to offer little hope for consensus.

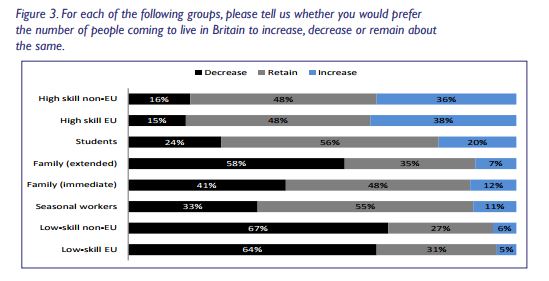

When you dig a little deeper, however, asking people what they think of different types of immigration, their responses show not just the scope for consensus but the failings of Leaver and Remainer referendum stereotypes to describe how people feel about the issue.

More than eight in 10 people, including 82 per cent of Leave voters, would support high-skilled immigration from the EU remaining at the same level as now, or even increasing, after Britain leaves the EU. Two-thirds (64 per cent) of the public, including 50 per cent of Remain voters would, however, support reductions in the number of low-skilled EU migrants coming to the UK.

Asked about specific professions, most people would prefer the number of doctors and nurses, scientists and researchers, engineers, IT specialists and business and finance professionals coming from overseas to stay the same or increase.

People also make allowances for those doing certain lower-skilled jobs that need filling: 75 per cent want the number of migrant care workers to either stay the same or increase, with majorities also happy for numbers of construction workers (63 per cent) and fruit-pickers (63 per cent) coming to the UK to stay the same or increase.

A new post-Brexit immigration system that differentiates between skilled and low-skilled EU immigration sounds like common sense to most people. In our new report, Time to get it right: Finding consensus on Britain’s future immigration policy, we set out how such a system could work.

The UK government should be clear that it will put in place controls to limit the levels of low-skilled and semi-skilled migration. There are various ways in which a quota system could be designed: it would be possible, for example, to reserve some quota allocations for specific sectors, such as hospitality, food and farming.

Britain would then maintain “skilled movement” – both ways – for those with a job above an agreed skills or salary threshold. Under such a scheme, there would be no numerical limit on the numbers of EU/EEA workers coming to take a job which is above a threshold, set at a salary level of £24,000 or by using the national qualification framework and standard occupational classification codes instead.

Such a system would be both more responsive to public and political choices but less flexible for employers – so there is a trade-off to be struck about where the right balance lies. But by offering to let EEA nationals have first option on all of the low-skilled migration that Britain has decided to accept, within those limits, this migration system could form part of an offer to the EU in the trade negotiations to come.

Engaging the public in the debate about what happens next on immigration will be a crucial part of the project to restore public confidence in the government’s ability to manage immigration. That has been undermined by successive governments: first under Labour, who failed to predict and then respond to the high migration levels prompted by A8 accession in 2004; and then by Conservative-led governments who set and failed to come close to meeting a net migration target that was grounded in neither policy nor reality.

Britain’s referendum choice is a reset moment for immigration policy – an opportunity to rebuild public trust and take some of the heat and anger out of a debate that has dominated politics for decades. Greater public engagement will reveal not more anger and discord but the common ground on which to base a future immigration policy that could secure political, business and public support.