In 1988, Julie Hayward, a canteen cook at Cammell Laird shipyards, won a decade-long legal battle to be paid the same as the yard’s painters and joiners. This landmark case established a curious principle in British law: that jobs bearing no resemblance to one another could be deemed of ‘equal value’ by tribunals and courts. Few noticed at the time, but such rulings would plant a fiscal timebomb in Britain’s public finances and corporate balance sheets, one that now threatens to detonate with spectacular force.

Birmingham City Council’s effective bankruptcy last year, with £1.1 billion already paid in equal value settlements and hundreds of millions more pending, is merely the most visible sign of the damage. Glasgow Council has quietly disbursed over £700 million. Meanwhile, Asda faces a potential £1.2bn liability after a February ruling that found store staff deserved the same pay as warehouse workers. Across the nation, essential services are being cut, and prices are rising to cover these mounting costs.

The culprit? A legal principle that defies common sense. Dinner ladies must be paid the same as bin men, classroom assistants the same as groundskeepers, checkout operators the same as warehouse workers – regardless of their fundamentally different working conditions, skill requirements, and market demands.

The roots of this crisis lie in well-intentioned but flawed legislation. While the 1970 Equal Pay Act sensibly required equal pay for the same work, a 1983 amendment, driven by European directives, expanded this to include jobs of ‘equal value’ even when fundamentally different in nature. The 2010 Equality Act simply consolidated these provisions without addressing their fundamental flaws.

These provisions went largely underutilised for years because they were complex and costly to pursue. Now that the dam has broken, we’re witnessing the inherent illogic of the law play out in real time.

Early test cases cemented this approach, with Julie Hayward’s 1988 victory being particularly significant. As a canteen cook at Cammell Laird shipyard in Birkenhead, Hayward earned substantially less than men in skilled trades. Despite her role being completely different from shipyard painters and joiners, an independent evaluator ruled that her work required comparable levels of skill, effort and responsibility. The House of Lords ultimately agreed after a 10-year legal battle, establishing the revolutionary principle that women could claim equal pay with men in entirely unrelated occupations. What began as one cook’s claim against a shipyard laid the foundation for thousands of similar cases to follow.

Few recognise that the NHS has long grappled with these exact problems. In 1997, the health service lost a significant legal battle when speech therapists (predominantly women) successfully argued they deserved the same pay as clinical psychologists (predominantly men). This triggered the creation of ‘Agenda for Change’ – a sprawling system where every NHS job is evaluated and placed into pay bands based on supposed equivalence.

This convoluted system, covering more than one million staff, creates absurd comparisons – where advanced high-speed driving of ambulances is deemed exactly equivalent to advanced keyboard use. Equal value claims haven’t just emerged recently – they’ve been quietly draining our healthcare system for decades before spreading to local councils and the private sector.

These principles later fuelled massive group actions against Birmingham City Council, where female cooks, cleaners, and care workers were awarded equal pay with refuse collectors and street cleaners. The claims involved over 5,000 women who discovered they had been denied bonus payments that their male colleagues received. The council effectively declared bankruptcy in 2023, citing these claims, which had already cost £1.1bn with an additional £760m in outstanding liabilities, as a principal cause of its financial demise.

Far from being isolated incidents, these equal value disputes are now accelerating across local governments nationwide. Coventry faces ‘millions’ in claims over men’s ‘task-and-finish’ perks. Brighton & Hove could owe tens of millions. The GMB union reports it is supporting claims in over 20 councils, and striking women workers in Scotland are active in Falkirk, Renfrewshire, West Dunbartonshire and beyond. These cases are going to cost billions that cash-strapped local authorities simply don’t have.

What’s driving this sudden resurgence? Not new legislation – the legal framework has remained largely unchanged since 2010. Instead, we’re seeing a confluence of several factors: a landmark 2012 Supreme Court ruling that extended the time limit for claims from six months to six years; increased union activism; and most importantly, the snowball effect of each successful case establishing precedents for the next.

Many councils became especially vulnerable after failing to properly implement job evaluation schemes after the 1997 Single Status Agreement – a deal meant to harmonise pay for council workers, but which many authorities never fully enacted due to the enormous costs involved. Birmingham’s massive settlement in late 2023 has inspired a new wave of claims, as workers and their representatives smell blood in the water.

The contagion has spread to the private sector with equal vigour. Britain’s major supermarkets face claims from 112,000 store workers demanding parity with warehouse staff. Asda recently lost a key ruling in February 2025, finding store roles equal in value to distribution roles despite their obvious differences. In August 2024, Next lost a similar case, owing £30m to store staff claiming parity with warehouse workers.

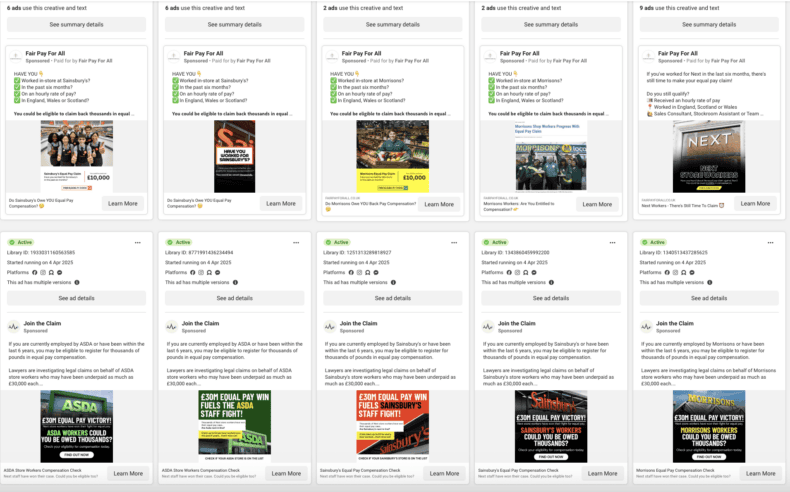

The no-win, no-fee legal industry has spotted a lucrative opportunity. On Facebook alone, there are currently 48 active ad campaigns targeting retail workers with promises of payouts ‘in the tens of thousands of pounds’. These advertisements specifically target employees from at least six major UK retailers including Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Next and Morrisons. Many ads prominently cite the success of past claims to encourage sign-ups, with digital advertising making recruitment remarkably efficient – turning what was once a complex legal process into an industrialised claims factory where lawyers can harvest potential claimants at scale.

.

The financial stakes are enormous. Tesco faces potential liabilities estimated at £4bn if its 47,000 claimants succeed – nearly four times its annual profit. Each victory emboldens more claims – law firms like Leigh Day are actively signing up additional employees, with their websites practically functioning as recruitment portals. If all these claims succeed, the costs will inevitably be passed onto consumers through higher prices – the last thing struggling households need during a cost-of-living crisis.

The UK stands almost alone in allowing such expansive equal pay claims – a legacy of European directives that Britain embraced more enthusiastically than many EU members themselves. While the EU principle of ‘equal pay for work of equal value’ exists across Europe, most countries have approached it more cautiously.

The United States takes a fundamentally different approach, limiting equal pay claims to substantially similar jobs – an American school cafeteria worker generally cannot claim parity with a garbage collector. Even Australia, an early adopter of equal value principles in 1972, implemented them primarily through centralised wage-setting rather than through retrospective litigation.

The fundamental problem isn’t the principle of fair pay – it’s the bizarre legal fiction that different jobs must be paid identically, and the retrospective application creating unpredictable liabilities stretching back years. What’s particularly absurd is that judges and lawyers, rather than employers and markets, are now determining the relative ‘value’ of completely different occupations.

Reform is urgently needed. Parliament should amend the Equality Act 2010 to limit these claims to truly comparable roles while strengthening measures against genuine gender-based pay discrimination. Having left the European Union, Britain can replace the EU-imposed equal value provisions with a more balanced approach that respects market realities while protecting against genuine discrimination.

While this situation creates windfalls for some claimants and their lawyers, it harms nearly everyone else: councils forced to cut essential services to pay legal bills, retailers passing costs to customers and the broader economy struggling with rising prices and diminished public services. Without reform, every council taxpayer and supermarket shopper in Britain will soon be footing the bill for this judicial fantasy – a legal doctrine that insists fundamentally different jobs must be paid identically regardless of market realities.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.